An argument based on curvature:

Given two points, think of all the segments that joint the two points.

The straightest one should be the shortest. By "straightest" I mean

the less curved. Curvature add length, that should be clear.

Now, take any plane intersecting the two points. Why plane? because it has

the least curvature of all surfaces (0 curvature).

Then if the plane is very shallow the curvature will be larger. Hence

the plane that, after intersecting both points, has the least curvature needs to be a plane that goes through the center. That is the arc of least curvature on the sphere. Then the shortest path is along a great circle.

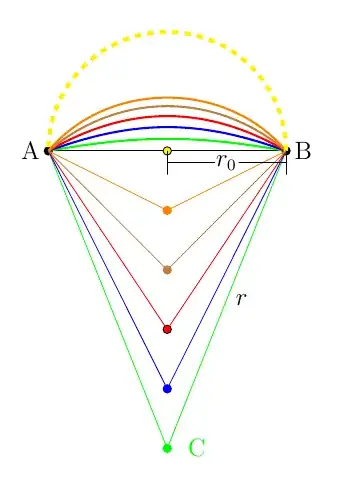

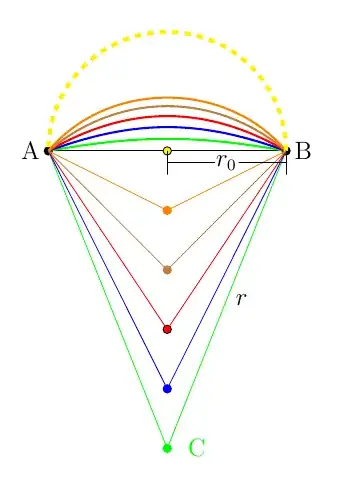

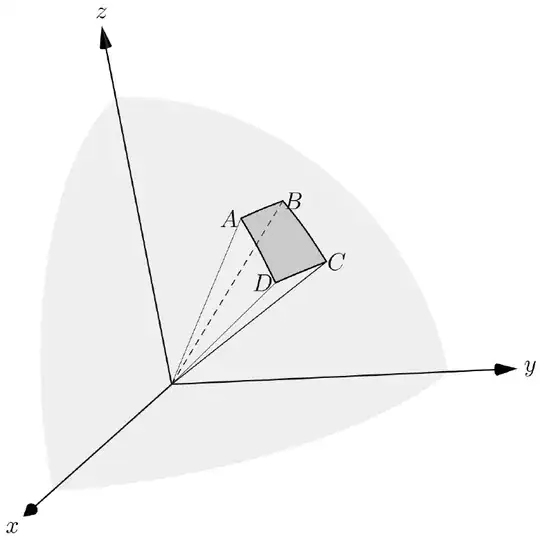

The figure should help to explain the idea.

Assume that the points $A$ and $B$ are in the sides of the sphere just in front of your eyes. The center of the sphere is the green point $C$.

This center is in the plane through the points $A$, $B$, and $C$ which

has a great circle when intersecting with the sphere and it is the plane

you are looking at (plane having the "flat" screen of your computer)

As the planes with the line $AB$ on them move away from the center (up in the

figure) the radius of curvature decreases (from $r$ which is the radius of the sphere down to $r_0= AB/2$ which is the radius of the intersection of a horizontal plane having the points $A$ and $B$.). See that the planes are being tilted because they are pinned to the line $AB$, so they are rotating down beyond $AB$, up toward the reader. That is, the arcs of circle that you see are all in different planes but drawn in the vertical plane. The green arc is the only arc in the vertical plane. The yellow is in the horizontal plane, and all the others are tilted planes between vertical and horizontal.

The color of the dot (center) matches the color of the curve. When the plane,

which started vertical rotated around the axis $AB$ until it becomes

horizontal, the intersection is a the yellow dashed circle (only half shown here) in the figure. That is, the largest it can get, being flat (no wiggling. Of course you can wind all you want and that is where there is no upper limit, but the longest of the shortest is half circle with radius $r_0=AB/2$, that is $r_0 \pi/2$).

It should be clear from this figure that the green path is the shortest (after the black which is a sphere of infinite radius and has the center down at infinity).

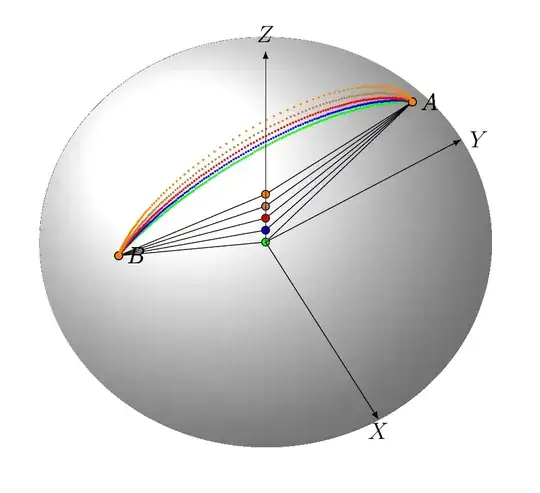

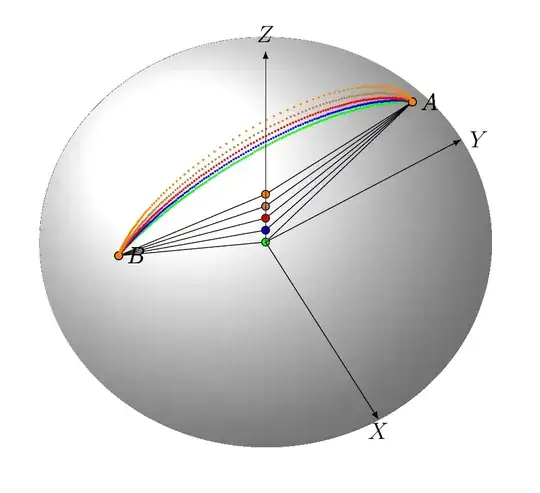

However I decided to include a 3D picture, which I believe explains better the problem. I am using the argument on this stack exchange post:

arc between two tips of vectors

to plot the figure. Each arc has 200 points, and as the center move up from the origin the points get more and more spread, indicating that the length of the segments increase.

The only curve along the sphere is the green curve. All others are above,

because they were rotated from the tilted plane to put them all in the

same vertical plane for easier comparison.

The TiKz code for this is in this stack exchange post:

draw an arc from point A to point B

columbus : a path is the graph of a function $[0,1] \to \mathbb R^{n}$ – krirkrirk Mar 08 '15 at 20:19