Could a “solar gravitational synchrotron ” use solar thermal steam rockets to launch spacecraft out of the solar system?

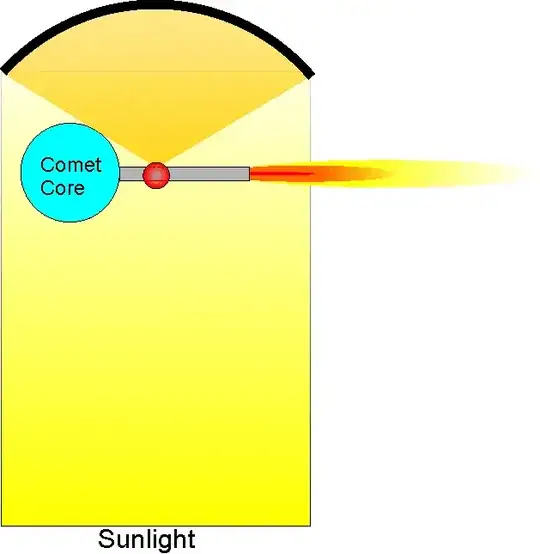

Solar thermal steam rockets https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Steam_rocket have appeal due to potentially large amounts of propulsive energy with little associated rocket engine mass. If In-Situ Resource Utilization (ISRU) could supply launch-free reaction mass (such as water from a comet-core near-Earth asteroid), then solar thermal rockets could potentially provide frugal propulsion (free mass + free energy) inside the inner solar system.

Solar thermal rockets have limited application outside the inner solar system because the intensity of solar radiation falls with the square of the distance from the sun. Attempts to achieve greater thrust by using a larger collector yield diminishing returns due to the square/cube relationship of structural mass to surface area.

A different strategy for using solar thermal steam rockets for access to the outer solar system is to accumulate velocity while remaining in the inner solar system until the target velocity is achieved. It is analogous to a synchrotron, with velocity increasing, and orbital period decreasing, each orbit.

The orbital period (and therefore velocity) of a satellite is related to the square root of the centripetal acceleration at that orbital radius. Higher centripetal acceleration (e.g.: larger central mass) means higher orbital velocity and shorter period. But this additional centrepital acceleration could also be supplied by thrust. In this case, by a solar steam rocket.

Ordinarily, the centripetal acceleration is provided solely by the gravitational attraction of the central body. But if the satellite has a thruster aligned radially with the orbit, thrust acceleration is added to the gravitational acceleration. Thrust of the same magnitude as the sun’s gravitational acceleration would result in an orbital period 29% shorter and an orbital velocity 41 % greater.

At an orbital radius of 1AU, a 41% increase in orbital velocity exceeds the solar system escape velocity.

The Earth’s orbital velocity is 29.9km/sec.

The solar escape velocity (at 1AU) is 42.1km/sec.

The sun’s gravitational acceleration at 1AU is 0.0059m/sec^2 (0.0006G) https://van.physics.illinois.edu/ask/listing/1063#:~:text=In%20metric%20units%2C%20on%20Earth,273.7%20meters%2Fsec%5E2

Note that the direction of thrust changes as the orbital velocity increases over the years. Initially it is tangential so all thrust is accelerating the spacecraft.. Eventually the thrust becomes radial so all thrust is being used to confine the orbital radius. At this time, the spacecraft has reached the maximum velocity attainable with this thrust and radius. Note also that the reaction mass is consumed over the period of the burn, so maximum thrust is attained at departure.

So, according to my calculator (which is, admittedly, making errors as it gets older), a satellite launched from Earth on a prograde heliocentric orbit and capable of 0.0006G acceleration could achieve solar escape velocity in less than a decade. Higher thrust would attain escape velocity sooner. or allow for higher velocity at departure.

It is interesting to note that the entire 10 year burn is an Oberth maneuver. The spacecraft is at a perpetual "perihelion" in that it is travelling faster than orbital velocity at that radius. The faster the orbital velocity, the more efficient the rocket.

The maximum velocity attainable with a “solar synchrotron” is limited by the centripetal thrust which the spacecraft can generate. The design will not allow crewed interstellar travel, but could be suitable for launching probes out of the solar system.

Are there physical (as opposed to engineering) factors prohibiting this strategy?