Here is the reentry plan:

Control your altitude during re-entry such that

There is enough air density to generate enough lift to equal 1g at your current speed. At an angle of attack that isn't too close to stall. Earlier in the flight you will not need anywhere near 1g of lift since you are somewhat in orbit, but it will not hurt to have it: just lower your angle of attack to lower your lift.

There isn't enough air to get 2g of lift. This ensures aerodynamic forces don't grow too high.

Here are the issues:

Supersonic handling. The glider as-is wouldn't be controllable at supersonic speeds without delta-wings or swing-wings, etc.

Hypersonic lift:drag ratio is around 4 unlike a sailplane which can reach 50. At optimum L/D ratio the lift coefficient is very low but at lower L/D ratio (of around 2) we get a lift of around 0.3. Subsonic airfoils can have a lift coefficient of around 1.0 at a safe margin from stall. This would mean 3x the force of a slow-gliding sailplane (not too extreme), unless your delta-wing is 3x fatter. In which case the wind-force would be similar to the subsonic case. You have 0.5g or so of drag-deceleration thus less sight-seeing time but that means a peak g-force of about 1.1g. No big deal.

Even with these two issues you can could stick your (pressure-gloved) hand into the airflow all the way through reentry and the force is no worse than a car on a freeway. Although it would feel different since it is a hypersonic flow at very low air density instead of subsonic at high density. You could see the shock-wave glowing and enveloping your hand. It would look pretty.

- Heat! Heat! Heat! The force of the wind is ~ρv^2 and is kept just below hurricane force. But heat is ~ρv^3. When v is mach 20 you can't have enough wind to generate the needed lift without getting incinerated. Your hull is made out of muileh which is a material that cannot melt no matter how hot it gets. But the payload and people aren't, so you have the issue of thermal soak.

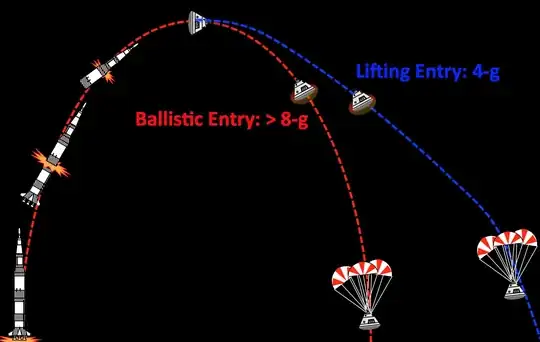

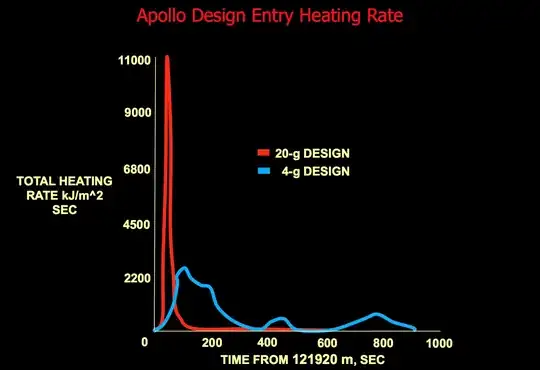

Ablative heat-shields saturate in terms of heat flux: Above a critical temperature the heat-shield starts to sublimate and the gas created prevents further heat flux to the shield. This means time is more important than temperature and you want to go in quick.

The shuttle has a non-ablative system and indeed reenters at a lower force. But there is still some advantage in not drawing reentry out too much (time still "wins" against temperature) even if there isn't as much of a saturation effect.

With this plan in mind:

At which (maximum) altitude & speed would the variometer tell 0 m/s vertical speed?

No limit here. You could (for a short time) maintain 0 m/s speed at any altitude/speed on this reentry.

What would be max temperature reached?

Probably around 1500C as that is the what the space-shuttle's relatively gentle reentry is. But for an even longer time than the space-shuttle.

Have there ever been real tests of deorbiting high finesse / low wing loaded gliding devices?

Not that I am aware of. Supersonic wings aren't "high finesse" (low chord). Keeping tensile strength high anywhere near 1500C is a real challenge and a long wing exposed to the airflow would be hard to heat-shield. As is protecting the avionics.

What would angle of attack be during the whole descent, until subsonic speed?

Near the zero-lift point in orbit (for my reentry plan), to highest in hypersonic but much below orbital speed and then lower again for the subsonic portion.

How does Coanda effect work at hypersonic speeds?

I am guessing it would be reversed. At low speed airflow tries to follow the curve of the ball. Air flowing over the top will end up getting deflected downward (lifting the ball upward) when it passes the upper-backside of the ball. Visa-versa for air passing the bottom of the ball. The Coandă effect uses skin-friction: a pitched baseball with backspin will slow down air on the lower side and speed up air on the upper side. This asymmetry generates a net upward lift.

At supersonic speeds the air doesn't have time to follow the curve of the ball. It slams into the front of the ball as a shock-wave and is flung outward at great speed. It will eventually be pushed back inward and fill the void left by the ball but (enough above mach 1) this is too far downstream to affect the ball. A back-spinning ball will tend to push the air ramming into the front of it up due to skin friction and thus push itself down which is opposite to the subsonic case.

;-)– user Apr 26 '17 at 11:03