The Nyquist Limit is frequently mentioned in the context of lens and sensor resolution.

What is it and what is its significance to photographers?

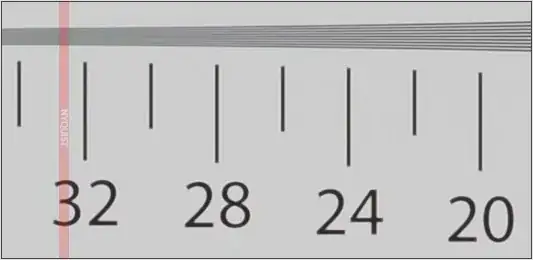

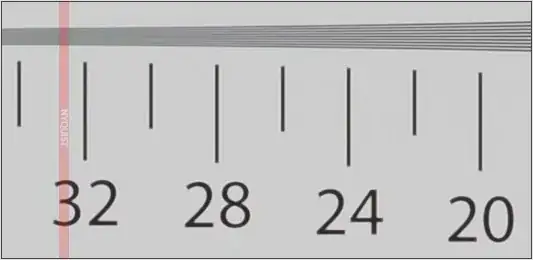

Here is an example of it being used by DPReview.com in their resolution testing.

The Nyquist Limit is frequently mentioned in the context of lens and sensor resolution.

What is it and what is its significance to photographers?

Here is an example of it being used by DPReview.com in their resolution testing.

Please note that the following is a simplification of how things actually work

Background:

In digital photography, a light pattern is focused by the lens onto the image sensor. The image sensor is made up of millions of tiny light-sensitive sensors whose measurements are combined to form a 2-dimential array of pixels. Each tiny sensor produces a single light intensity measurement. For simplicity, I will look at the 1-dimensional case. (Think of this as a slice that looks at only a single row of pixels).

Sampling:

Our row of tiny sensors, each of which is measuring a single point of light, is performing sampling of a continuous signal (the light coming through the lens) to produce a discrete signal (light intensity values at each evenly spaced pixel).

Sampling Theorem:

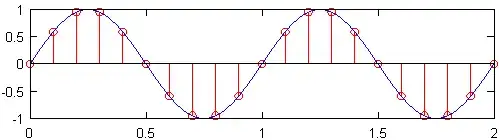

The minimum sampling rate (i.e., the number of sensors per inch) that produces a signal that still contains all of the original signal’s information is known as the Nyquist rate, which is twice the maximum frequency in the original signal. The top plot in the figure below shows a 1Hz sine wave sampled at the Nyquist rate, which for this sine wave is 2Hz. The resulting discrete signal, shown in red, contains the same information as the discrete signal plotted beneath it, which was sampled at a frequency of 10Hz. While a slight over simplification, it is essentially true that no information is lost when the original sample rate is known, and the highest frequency in the original signal is less than half the sample rate.

Effects of under sampling:

If the sample frequency were less than 2 times the maximum frequency of the signal, then the signal is said to be under sampled. In that case, it is not possible to reconstruct the original continuous signal from the discrete one. An illustration of why this is the case can be found in the figure below. There, two sine waves of different frequencies sampled at the same rate produce the same set of discrete points. These two sine waves are called aliases of each other.

All discrete and digital signals have an infinite number of aliases, which correspond to all the sine waves that could produce the discrete signals. While the existence of these aliases may seem to present a problem when reconstructing the original signal, the solution is to ignore all signal content above the maximum frequency of the original signal. This is equivalent to assuming that the sampled points were taken from the lowest possible frequency sinusoid. Trouble arises when aliases overlap, which can happen when a signal is under sampled.

But Photographs Don't Look Like Sinusoidal Waves. How is all this Relevant?

The reason all of this matters for images is that through application of the Fourier Series, any signal of finite length can be represented as a sum of sinusoids. This means that even if a picture has no discernable wave pattern, it can still be represented as a sequence of sinusoids of different frequencies. The highest frequency that can be represented in the image is half the Nyquist rate (sampling frequency).

Meanings of Similar Terms:

Nyquist rate - The lowest possible sampling frequency that can be used while still guaranteeing the possibility of perfect reconstruction of the original continuous signal.

Nyquist frequency - The highest frequency continuous signal that can be represented by a discreet signal (for a given sampling frequency).

These two terms are two sides of the same coin. The first gives you a bound on sampling rate as a function of max frequency. The second gives you the max possible frequency as a function of sampling rate. See Wikipedia: Nyquist frequency for further reading.

Nyquist Limit is another name for Nyquist frequency. See wolfram.com: Nyquist Frequency

The Nyquist Limit is mostly used in digital sound recording, but it also applies to digital photography.

In digital sound recording, the highest frequency sound that you can possibly record is half of the sampling frequency. A sound recording av 44100 kHz can not record any sound frequencies above 22050 Hz.

In photography it means that you can't possibly capture a wave pattern where the waves are closer together than two pixels.

In sound recording, everything is frequencies, so the Nyquist Limit is always relevant. In photography you don't often have wave patterns that are affected, so it's mostly used as a theoretical limit of the resolution of the sensor.

You can see the effect of this limit in a few situations where there is a horisontal or vertical wave patterns in a photo, like for example taking a picture where there is a window at a distance with the blinds pulled. If the blades in the blind are closer than two pixels, you can't distinguish the separate blades. However, you are more likely to see a wave pattern that is not exactly horizontal of vertical; it is in that case you will instead see the effect of jagged edges or moiré patterns which occur before the Nyquist Limit.

Just to add to the previous answers... if you have a pattern beyond the Nyquist limit, you may experience aliasing — i.e. it may show as a lower frequency pattern in the image. This used to be very apparent on things like checked jackets on TV. Therefore, you do need a low pass anti-aliasing filter before sampling so that this artifact is not a problem.