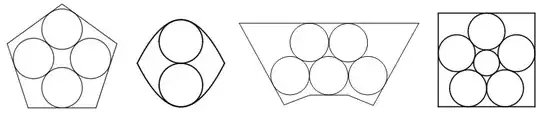

Circular coins in a frame may all be stuck in their positions; for example:

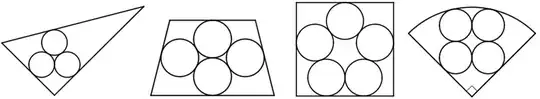

Another possibility is that they can all move simultaneously; I claim the following examples:

It is not always obvious that the coins can move, and it can be quite tedious, or nearly impossible, to show algebraically that the coins can move. We can use animations (example1, example2, example3), but that's not quite rigorous.

Are there general principles that allow us to easily determine whether coins in simple arrangements in a frame can all move?

Here are some of my attempts at formulating such general principles.

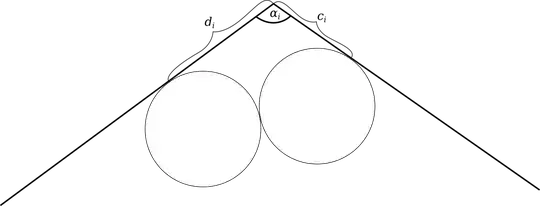

- Earlier I conjectured that if circular coins of any sizes are in a convex polygonal frame, with each coin touching exactly one edge, then all the coins can move. A counter-example, using coins of different sizes, was given.

- Then I proposed a second conjecture that was like the first one, except it required the coins to be equal size. A counter-example was given.

- My latest idea is to add the condition that the coins must be in a ring (i.e. every coin touches exactly two other coins), but I would not be surprised if there's yet another counter-example.

Anyway, I open to floor to general principles that are useful in determining if coins in simple arrangements in a frame can move.

(I have no strict definition of "simple arrangements". Let's say, just a few coins, and just a few sides and/or "natural" curves like circular arcs, parabolas, etc. I exclude arrangements in which a coin can move without disturbing others, and arrangements in which the coins can rotate as a single rigid body about a fixed point.)