EDIT: I uploaded a higher-resolution, correctly flipped image for convenience. Upon further inspection, it turns out there is a hidden small-scale fractal structure. An uncompressed 10k zoom on the interesting part can be found here.

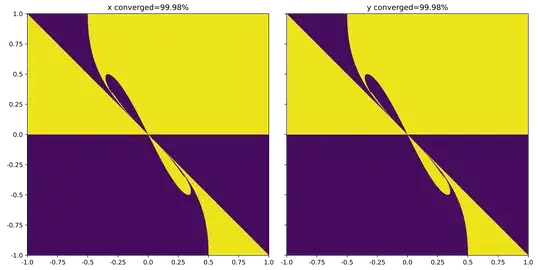

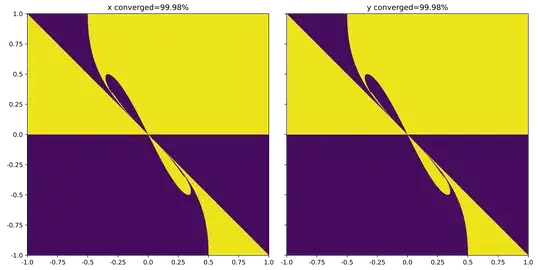

EDIT: This is what the basins of attraction look like. It seems that indeed there is always converges against $x=y=±\sqrt{2}$, except for the lines $x=-y$ and $y=0$ and a complicated bow-tie figure. Python source code, using JAX at the bottom.

The line $x=0$ is a well-behaved singularity, because

$$

\begin{pmatrix}±0\\y\end{pmatrix}

⟼

\begin{pmatrix}y \\ ±∞ \end{pmatrix}

⟼

\begin{pmatrix}±∞\\ 1/y\end{pmatrix}

⟼

\begin{pmatrix}1/y\\ y\end{pmatrix}

$$

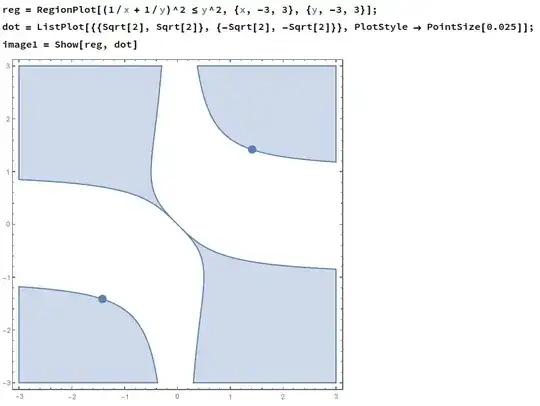

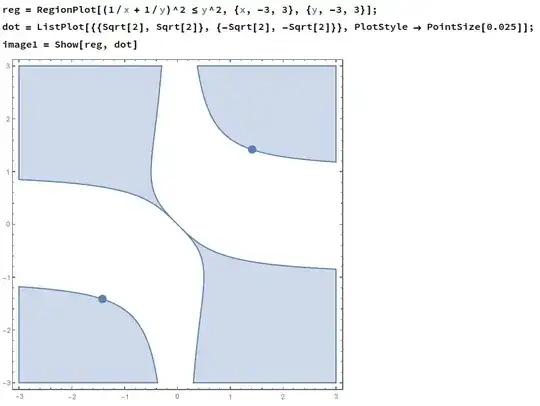

The iteration can be encoded in the function $f(x, y) = (y, \tfrac{1}{x} + \tfrac{1}{y})$. Note that

$$

\|f(x,y)\|_2^2 ≤ \|(x,y)\|_2^2

⟺ y^2 + (\tfrac{1}{x} + \tfrac{1}{y})^2 ≤ x^2 + y^2

⟺ (\tfrac{1}{x} + \tfrac{1}{y})^2 ≤ x^2

$$

Within regions where this equality is strict, the function is contractive. However, both a plot and analysis reveal that the critical points $x=y=±\sqrt{2}$ lie exactly on the boundary.

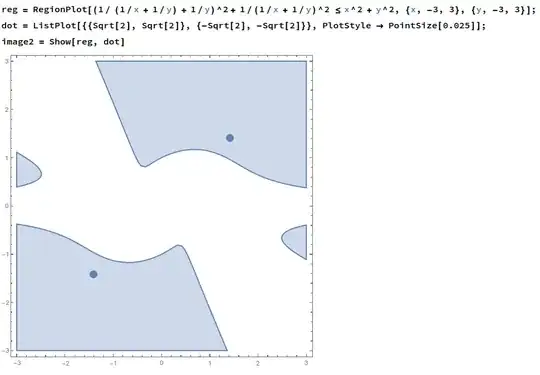

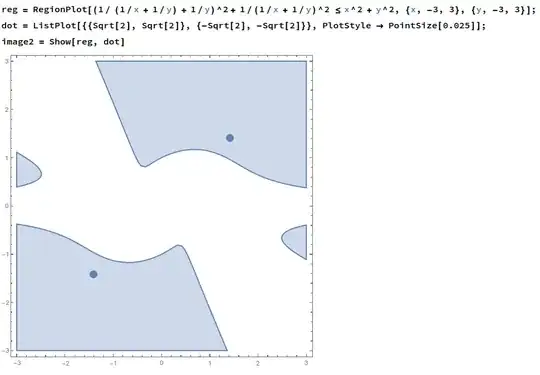

However, if we move to the second iteration we have:

$$

\|f^{(2)}(x,y)\|_2^2 ≤ \|(x,y)\|_2^2

⟺ \Big(\tfrac{1}{\frac{1}{x} + \frac{1}{y}}\Big)^2 + \Big(\tfrac{1}{y} + \tfrac{1}{\frac{1}{x} + \frac{1}{y}}\Big)^2 ≤ x^2 + y^2

$$

Now, we see the critical point lie well inside the region and thus we have convergence by Banach's Fixed Point Theorem.

There are still some technical holes to fill (*), but I think this should give a rough idea of why there is convergence.

Hypothesis/Conjecture: Let $C_n = \{(x, y) ∣ \|f^{∘n}(x,y)\|_2^2 < \|(x,y)\|_2^2\}$ be the region for which $f^{∘n}=f∘f\circ\ldots∘f$ is contractive. Then, in the set-theoretic limit

$$\lim\limits_{n\to ∞} C_n = ℝ^2\setminus \{(x,y) \mid x=-y ∨ x=0 ∨ y=0\}$$

(*) Basically, we can formulate an argument like this: We already know $x=y=\sqrt{2}$ is a fixed point. By (Lipschitz-) continuity, $f$ maps a ball around the fixed point to a nbhd. of the fixed point. Choose the original ball small enough such that it is contained in the contractive region. Then its image must be a subset of itself since $\|f(x)-x^*\| =\|f(x)-f(x^*)\|≤\|x-x^*\|$, hence $f$ restricted to this ball satisfies all technical necessary conditions for applying Banach's Fixed Point Theorem.

Source Code

import jax

import jax.numpy as np

from tqdm import trange

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

jax.config.update("jax_enable_x64", True)

@jax.jit

def f(a):

x, y = a[0], a[1]

return np.array([y, 1/x + 1/y])

N = 2**12 # 4k resolution

xmin, xmax = -.5, +.5

ymin, ymax = -.5, +.5

X = np.linspace(xmin, xmax, num=N)

Y = np.linspace(ymin, ymax, num=N)

Z = np.stack(np.meshgrid(X, Y))

for k in trange(1000):

Z = f(Z)

fig, axes = plt.subplots(ncols=2, figsize=(12, 6), tight_layout=True,

sharex=True, sharey=True, subplot_kw=dict(box_aspect=1))

for ax, im, title in zip(axes, Z, ("x", "y")):

img = ax.imshow(im, interpolation="none", vmin=-1.5, vmax=1.5)

converged = np.mean(np.isclose(im, np.sqrt(2)) | np.isclose(im, -np.sqrt(2)))

ax.set_xlim(xmin, xmax)

ax.set_ylim(ymin, ymax)

ax.set_xticks(np.linspace(0, N, 9))

ax.set_yticks(np.linspace(0, N, 9))

ax.set_xticklabels(np.linspace(xmin, xmax, 9))

ax.set_yticklabels(np.linspace(ymin, ymax, 9))

ax.set_title(title+f" {converged=:.2%}")

fig.savefig(f"4248805_{N}px.png", dpi=N/fig.get_size_inches()[1])