New revised answer, using only elementary properties of sequences: In order to avoid scattering too many $\sqrt{2}$'s in the text I will

normalize differently and

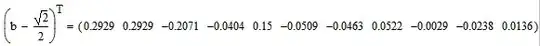

write $a_n=\sqrt{2} x_n$. The $x_n$'s then verify:

$$ x_{n+2}=\frac12 \left( \frac{1}{x_{n+1}} + \frac{1}{x_n} \right).$$

We will show the following:

Theorem: For any $x_0,x_1>0$ the sequence $x_n$ converges

to 1. Moreover,

if $\delta_0= \max\{x_0,x_1,\frac{1}{x_0},\frac{1}{x_1}\} -1$

(which is $\geq 0$) then

for all $n\geq 0$:

$$ |x_n-1| \leq 2

\left(\frac{3}{4}\right)^{\lfloor n/3 \rfloor}

\delta_0 .$$

[This implies that the original sequence $a_n$ converges to $\sqrt{2}$

at the same exponential rate, whence solving the stated problem.]

Proof of the Theorem:

We will use a couple of times that for $b,c>0$

we have the straightforward bound (which is easily seen to be

equivalent to $(b-c)^2\geq 0$):

$$ \frac{1}{2} \left(\frac{1}{b} + \frac{1}{c}\right)

\geq \frac{2}{b+c} \ \ \ (*)$$

Define for $\delta>0$ the interval:

$$ I_\delta = \left[\frac{1}{1+\delta}, 1+\delta \right].$$

If $\delta>0$ and $x_n,x_{n+1}\in I_\delta$ then clearly

$$\frac{1}{1+\delta}\leq x_{n+2}=\frac{1}{2}

\left( \frac{1}{x_{n+1}}+\frac{1}{x_n}\right)\leq 1+\delta$$

so by induction $x_{n+k}\in I_\delta$ for every $k\geq 0$.

Let us say that the pair $(x_{n},x_{n+1})$ is 'well-separated' if

$x_{n}\leq 1\leq x_{n+1}$ or $x_n\geq 1\geq x_{n+1}$. If $(x_{n},x_{n+1})$

is not well-separated then

the pair $(x_{n+1},x_{n+2})$ is going to be well-separated

(e.g. if $x_n,x_{n+1}\leq 1$ then $x_{n+2}=1/2(1/x_{n}+1/x_{n+1})\geq 1$)

so

at least every second consecutive pair is necessarily well-separated.

When $(x_n,x_{n+1})$ is a well-separated pair then

$$ x_{n+2} \leq \frac{1}{2} \left( 1 + (1+\delta) \right) =1 + \delta/2$$

and

$$ x_{n+2} \geq \frac{1}{2} \left( \frac{1}{1+\delta} + \frac{1}{1} \right)

\geq \frac{2}{2+\delta} = \frac{1}{1+\delta/2}$$

where I used the bound $(*)$. So $x_{n+2}\in I_{\delta/2}$.

But then we also have:

$$ x_{n+3} \leq \frac{1}{2} \left( (1+\delta/2) + (1+\delta) \right)

=1 + \frac34\delta$$

and (again using the bound $(*)$):

$$ x_{n+3} \geq \frac{1}{2} \left( \frac{1}{1+\delta/2} +

\frac{1}{1+\delta} \right)

\geq \frac{2}{2+\frac32 \delta} = \frac{1}{1+\frac34 \delta}$$

So $x_{n+3}\in I_{\frac34 \delta}$.

If the pair $(x_{n},x_{n+1})$ was not well-separated then

$(x_{n+1},x_{n+2})$ is well-separated and we obtain the same inclusions after

one more iteration. Combining the two cases

we find that whenever

$x_{n+k}\in I_\delta$ for $k\geq 0$ then

$x_{n+3+k} \in I_{\frac 34 \delta}$ for $k\geq 0$.

In particular when $x_{k}\in I_{\delta_0}$ for all $k\geq 0$

we obtain through induction that

$$x_{3n +k} \in I_{(\frac{3}{4})^n \delta_0}, \ \ n,k\geq 0$$

and from this

$$|x_{3n +k}-1| \leq 2 (\frac{3}{4})^n \delta_0, \ \ \ n,k\geq 0$$

which translates into the stated estimate whence proving the theorem.