I was going through the Dinosaur book by Galvin where I faced the difficulty as asked in the question.

Typically application developers design programs according to an application programming interface (API). The API specifies a set of functions that are available to an application programmer, including the parameters that are passed to each function and the return values the programmer can expect.

The text adds that:

Behind the scenes the functions that make up an API typically invoke the actual system calls on behalf of the application programmer. For example, the Win32 function

CreateProcess()(which unsurprisingly is used to create a new process) actually calls theNTCreateProcess()system call in the Windows kernel.

From the above two points I came to know that: Programmers using the API, make the function calls to the API corresponding to the system call which they want to make. The concerning function in the API then actually makes the system call.

Next what the text says confuses me a bit:

The run-time support system (a set of functions built into libraries included with a compiler) for most programming languages provides a system-call interface that serves as the link to system calls made available by the operating system. The system-call interface intercepts function calls in the API and invokes the necessary system calls within the operating system. Typically, a number is associated with each system call, and the system-call interface maintains a table indexed according to these numbers. The system call interface then invokes the intended system call in the operating-system kernel and returns the status of the system call and any return values.

The above excerpt makes me feel that the functions in the API does not make the system calls directly. There are probably function built into the system-call interface of the runtime support system, which are waiting for an event of system call from the function in the API.

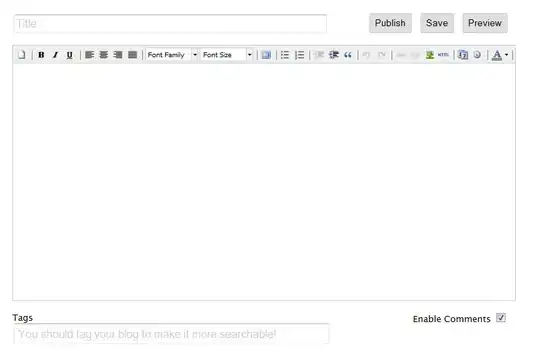

The above is a diagram in the text explaining the working of the system call interface.

The text later explains the working of a system call in the C standard library as follows:

which is quite clear.