This is a somewhat unintuitive behavor of variables. It happens because, in Python, variables are always references to values.

Boxes and tags

In some languages, we tend to think about variables as "boxes" where we put values; in Python, however, they are references, and behave more like tags or "nicknames" to values. So, when you attribute 1 to item, you are changing only the variable reference, not the list it is pointing to.

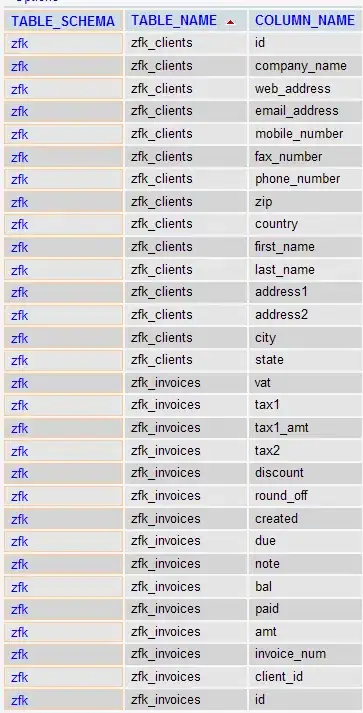

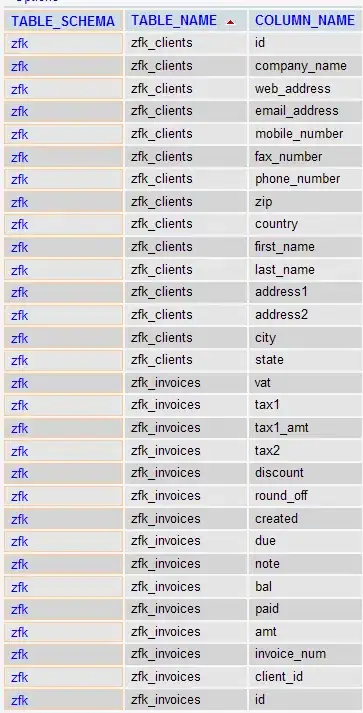

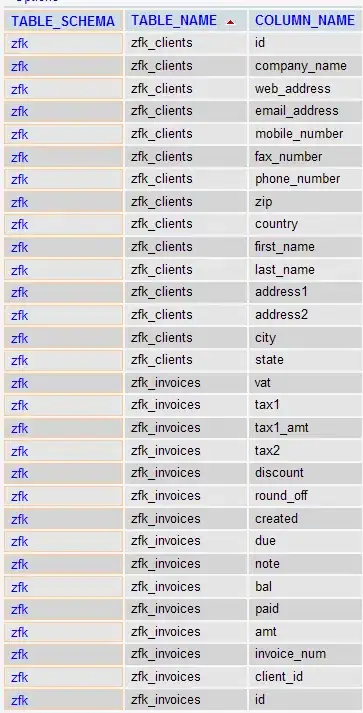

A graphic representation can help. The image below represents the list created by alist = [[1,2], [3,4], [5,6]]

Given that, let's see what happens when we execute your first loop.

The first loop

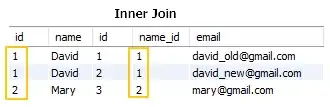

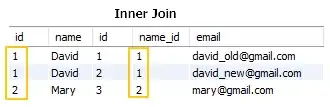

When you execute for item in alist, you are asking the interpreter to take each value from the list, one per time, put it on the variable item and do some operation in it. In the first operation, for example, we have this new schema:

Note that we do not copy the sublist to item; instead, we point to it through item. Then, we execute item = 1 — but what does it mean? It mean that we are making item point to the value 1, instead of pointing to the sublist:

Note that the old reference is lost (it is the red arrow) and now we have a new. But we just changed a variable pointing to a list — we did not alter the list itself.

Then, we enter to the second iteration of the loop, and now item points to the second sublist:

When we execute item = 1, again, we just make the variable point to aonther value, without changing the list:

Now, what happens when we execute the second loop?

The second loop

The second loop starts as the first one: we make item refer to the first sublist:

The first difference, however, is that we call item.append(). append() is a method, so it can change the value of the object it is calling. As we use to say, we are sending a message to the object pointed by item to append the value 10. In this case, the operation is not being made in the variable item, but directly in the object it refers! So here is the result of calling item.append():

However, we do not only append a value to the list! We also assign the value returned by item.append(). This will sever the item reference to the sublist, but here is a catch: append() returns None.

The None value

None is a value that represents, basically, the unavailability of a relevant value. When a function returns None, it is saying, most of the time, "I have nothing relevant to give you back." append() does change its list directly, so there is nothing it needs to return.

It is important because you probably believed item would point to the appended list [1, 2, 10], right? No, now it points to None. So, you would expect the code below...

alist = [[1,2], [3,4], [5,6]]

for item in alist:

item = item.append(10)

print(item)

To print something like this:

[1, 2, 10]

[3, 4, 10]

[5, 6, 10]

But this does not happen. This is what happens:

>>> alist = [[1,2], [3,4], [5,6]]

>>> for item in alist:

... item = item.append(10)

... print(item)

...

None

None

None

Yet, as we commented, the append() method changed the lists themselves. So, while the item variable was useless after the assignment, the final list is modified!

>>> print alist

[[1, 2, 10], [3, 4, 10], [5, 6, 10]]

If you want to use the appended list inside the loop, just do not assign the method returned value to item. Do this:

>>> alist = [[1,2], [3,4], [5,6]]

>>> for item in alist:

... item.append(10)

... print item

...

[1, 2, 10]

[3, 4, 10]

[5, 6, 10]

This works because item will still point to the list.

Conclusion

References are somewhat complex to understand at first, let alone master. Yet, they are really powerful and can be learned if you follow examples etc. Your example is a bit complicated because there is more happening here.

The Python Tutor can help you understand what is going on, because it executes each step graphically. Check your own code running there!