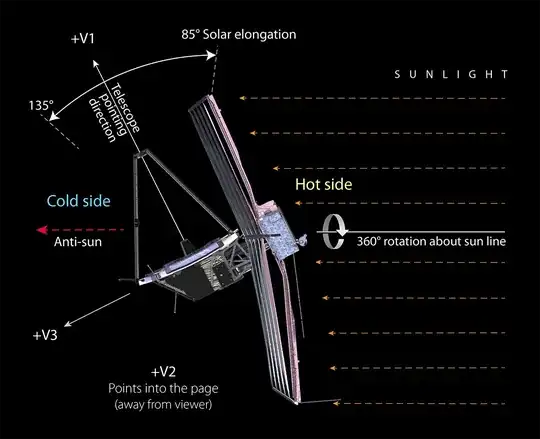

The James Webb Space Telescope has some very specific positioning requirements; the second Lagrange point and the heat shield positioning being at the top of my mind.

Do these constraints eliminate the possibility of pointing the telescope at any general region of space? For example, a telescope positioned at the south pole can never image Polaris because Earth is always obstructing the view.

For the JWST at first I thought you could analogize this to "the belt of space always hidden behind the earth and the sun", but then I realized that part of space isn't always hidden, but it instead would simply be unavailable on a "rotating" basis depending on the time of year; after all what is hidden behind the sun in January is out the opposite direction during summer. But my astronomy foo is weak and I wonder if there are other aspects of the deployment and operation that could affect things that I'm unaware of.

Are there any portions of the sky that the JWST will never be able to image because of constraints on it's positioning?

It also wont bother looking directly at Jupiter and Saturn, as it’s sensors would just be over exposed as I understand it. But technically it could when the orbits are right.

– Eric G Jan 10 '22 at 18:46Can it see behind itself? Can it see through objects? Can it see infinitely far? What else is there?

– Robbie Goodwin Jan 11 '22 at 22:18