Jupiter appears to approximately follow Lambert's cosine law as it looks darker towards its limbs when viewed from the same direction as from where the Sun shines on it. Here an image from the article Hubble takes close-up portrait of Jupiter that shows it in opposition:

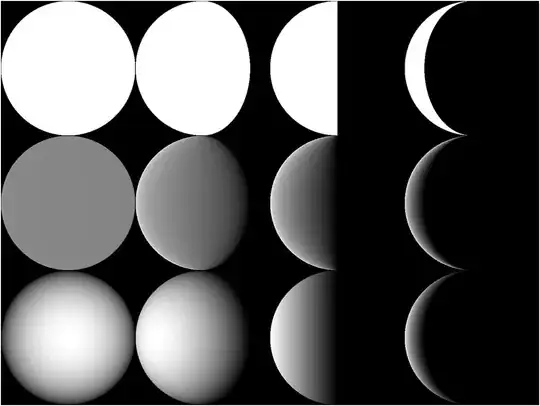

Now there is the Lommel-Seeliger law which is a good first approximation to diffuse reflection. Here is an image that shows its effects in the middle, while an approximately Lambertian surface is at the bottom:

The Lommel-Seeliger sphere appears flat at zero phase angle. The Lommel-Seeliger law is derived by considering what happens to a beam of light that enters a medium. Therefore, my assumption is that it should be a good approximation to atmospheres and gas giants, too. However, Jupiter apparently proves me wrong. Why does it not look flat?

An example of a celestial body that appears flat at zero phase angle is the Moon. It is covered by lunar regolith that is a medium of pulverized particles.