This is actually quite interesting problem, which has a few levels to it:

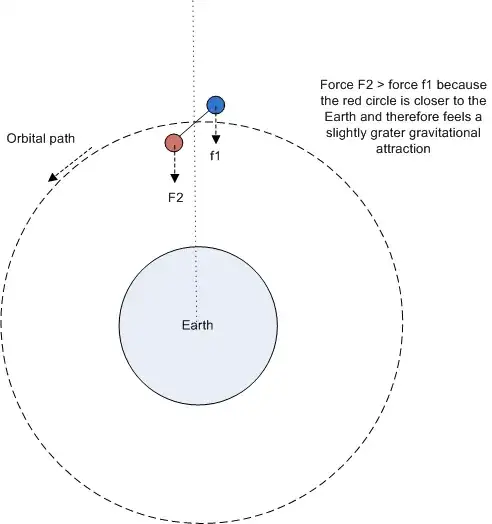

- In first order approximation, there is a tendency to align the orbiting body vertically with its mass extending as much as possible either above or below the orbit without difference if it is up or down. This is the effect described in the linked wikipedia article.

- But there is higher-order effect too, which adds some minuscule preference to orientation with largest extending mass downwards.

- Last but not least, this is not limited to orbiting bodies. You will get exactly same behavior (with some minor differences in factors) for vertical free fall. So even freely falling objects will tend to align itself vertically! (Even without effect of Earth rotation, but OTOH in most cases the duration of any realistic free fall will be too short for this to be noticeable.)

In order to analyze the situation, one need to consider non-inertial coordinate frame. Either rotating in case of space station or constantly accelerating in case of vertical free fall. In both situations there will be gravity force + an inertial force. Both of them acts proportional to the mass and at all single points of the body, so it is easy to add them together in each point.

For a space station, the inertial force is centrifugal one. Proportional to angular velocity of the orbit (constant, let's not make things more complicated by elliptical orbits) and distance from Earth centre. Gravity is inversely proportional to square of this distance. Total force on any point with mas $m_x$ will be then:

$$

F_x = F_G - F_C = m_x \left[{G\cdot M_E \over r_x^2} - \omega^2\cdot r_x\right]\,,

$$

$r_x$ is distance from earth centre to the respective point, $\omega$ is angular speed of reference frame rotation, $G$ gravitational constant and $M_E$ Earth mass. Positive force points inwards into Earth centre.

Let's pick an reference frame which revolves with such angular speed that resulting force will be zero at some radius $r$ and split $r_x$ into this "mean" radius $r$ where forces are in balance and distance $a_x$ from this altitude ($r_x = r + a_x$):

$$

F_x = m_x \cdot G \cdot M_E \left[{1\over (r+a_x)^2} - {r + a_x\over r^3}\right]\,.

$$

Note that resulting force points upwards for positive $a_x$ and downwards for negative $a_x$. So what is holding a space station in its orbit then? As soon as some perturbation shifts it a bit lower, it starts accelerating down to the ground. Or does it? Turns out that there is one more inertial force in the rotating frame, namely Coriolis force, which acts on objects which move inside the reference frame.

So if object starts to "fall down" from its orbit, this extra velocity results in Coriolis force accelerating it in direction of frame rotation and this tangential component in turn induces Coriolis force upwards. At the end this object starts "orbiting" a point in rotating reference frame located at original radius $r$. What does it mean? Well, an elliptical orbit (maybe there is something to epicycles at the end :) ). But to not complicate things further, we will analyze only static configurations in perfectly circular orbit (any mas below equilibrium height pulling down will be compensated by other mass above this height pulling up) where Coriolis force equals zero.

Staying with gravitational and centrifugal forces only, let's integrate the expression with respect to $a_x$. The result will be potential energy of a point mass in this pseudopotential created by combination of gravitational and centrifugal force with respect to distance from nominal orbit radius:

$$

E_x=-{3G\cdot M_E\over 2r^3}\cdot m_x\cdot a_x^2 \cdot {r+a_x/3\over r+a_x}\,.

$$

Zero energy level was set for zero $a_x$, that is at the "nominal" orbit radius. Any mass above or below it will have negative potential energy.

Note that last fraction will be really close to 1 for $a_x \ll r$ (size of station compared to distance to Earth centre) and remaining term is a quadratic potential without any preference for up or down ($a_x$ is squared).

So the lowest energy is with as much of the mass sticking as much up or down as possible, but without any preference for up or down.

The ${3G\cdot M_E\over 2r^3}$ equals numerically $2\,\rm \mu J/(kg\cdot m^2)$. To get a feeling how much it is: it is similar to a rotational energy of object revolving around its own axis with period about 1 hour. So this first-order tidal stabilization is strong enough to have noticeable effect on such slow movement (roughly independently of size or mass of spacecraft/spacestation).

The up and down preference comes from the last term. It can be approximated as $1-2a_x/3r$, so same mass sticking the same distance above $r$ will have lower energy than when placed same distance below (the the energy is negative, so bigger coefficient means lower energy).

In avoid forces pushing object away from circular orbit mass distribution needs to stay such that total energy is a its maximum (zero derivative) with respect to vertical shift. Any upside down turn needs to be balanced by realigning center of gravity. Generally, "heavier" part here needs to be interpreted in terms of moments of inertia or, for the last fraction, third power of distance from center of mass. So it there is not much specific to be stated for generic object without taking its detailed geometry into account.

Playing with some specific numbers for two small spheres in vertical position either heavier down or up results in relative differences in energy at order of 0.1‰ to 0.01‰ preferring heavier at the bottom. So difference is really small, but existing.

And to get back to free fall. (Lets neglect the Earth rotation -- either free falling at the pole or high from the space without any tangential velocity -- to get the other extreme case). Here the inertial force is caused by constant acceleration by gravity and it is simply equal to acceleration of coordinate frame times mass independent of $a_x$:

$$

F_{x,fall} = F_G - F_A = m_x \left[{G\cdot M_E \over (r+a_x)^2} - {G\cdot M_E \over r^2}\right]\,,

$$

After integrating with respect to $a_x$ we get a similar expression for energy as above:

$$

E_{x,fall}=-{G\cdot M_E\over r^3}\cdot m_x\cdot a_x^2 \cdot {1\over 1+a_x/r}\simeq-{G\cdot M_E\over r^3}\cdot m_x\cdot a_x^2 \cdot \left(1 - {a_x\over r}\right)\,.

$$

So the quadratic potential is in this situation weaker by factor 1.5 compared to orbiting case and higher order up--down preference factor is higher by the same factor, otherwise no difference.