One of the more interesting proposed uses of a Saturn V was to launch a manned flyby of Venus. Some of the cargo would have been stored inside the tank of the upper stage, which would be retained throughout most of the flight. The question I have is how large of a payload could the Saturn V have launched to Venus, and is it even remotely reasonable such a mission could have worked?

-

7The linear distance at close approach is misleading; space trajectories don't work that way. – Russell Borogove Mar 14 '19 at 15:31

1 Answers

It takes surprisingly little delta-v to reach Venus for a flyby -- about 3850 m/s from LEO instead of the 3200 m/s or so required to get to the moon -- so while the payload would have to be reduced from the normal Apollo mission, it wouldn't have been impossible.

For Apollo 17, if we consider the payload to be the CSM, LM, and LM adapter, the total is 48.6 tons (per Apollo By The Numbers). For a trans-Venusian payload, my calculations say the mass budget comes down to around 31 tons.

That seems a prohibitive reduction, but for Apollo, the payload was largely propellant: lunar orbit insertion and trans-Earth injection on the CSM, descent and ascent for the LM. In total this was about 29 tons of propellant. Since there was no orbital insertion or landing planned, the only propellant needed would be for course correction, aborts, and braking for re-entry. The Bellcomm study proposed 8.6 tons of CSM propellant, dominated by the requirement for an abort within 45 minutes of trans-Venusian injection. With the reduced propellant load and elimination of the Lunar Module, there's enough payload budget to fully equip the living space.

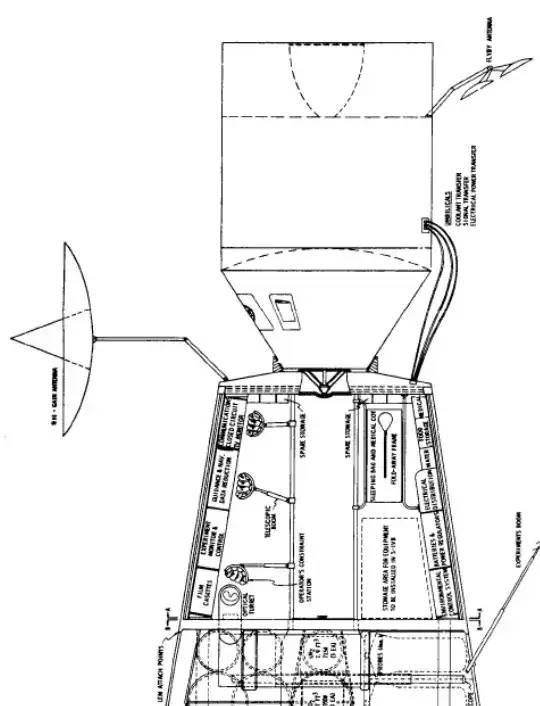

From the diagram in the Wikipedia article, you can see the interior structure of the service module is shortened by about 40% to allow for the propulsion system to be recessed within the original dimensions, allowing more useful volume in the Environmental Support Module below. Eliminating most of the propellant tankage volume makes this possible:

Overall the mission seems feasible. The trans-Venusian spacecraft is somewhat comparable to Skylab, which was also built into an S-IVB-shaped hull.

The longest Skylab mission was almost three months; this proposal would take 13 months: 4 months out to Venus and 9 months back! That is a long time for three people to live in an enclosed space, even a fairly roomy one. The Bellcomm study outlines requirements for environmental support; waste water would need to be recycled and oxygen recovered from CO2, neither of which was required by the short Apollo flights.

I'm a little skeptical of the wet workshop concept. Anything that you want to put in the tank at launch has to stand up to liquid hydrogen temperatures, and everything else has to be installed by the astronauts after the injection burn and vent, and thus needs to be stored somewhere else during launch.

Radiation exposure over a year-long mission outside of Earth's magnetosphere is also concerning. The Bellcomm study indicates that neither the Apollo CM nor the S-IVB tanks have thick enough shielding for a one-year mission, so additional shielding mass would have to be added to the S-IVB.

All in all it probably wasn't a good idea. It's a huge investment for a three hour crewed flyby; it couldn't accomplish anything that couldn't be done by a few Mariner-type missions.

If you want to do a similar Mars mission, by the way, you need to scrape down another 7200kg of payload. Good luck with that...

- 168,364

- 13

- 593

- 699

-

1Reading that Bellcomm study is...interesting. Written before any Apollo missions had flown. – Organic Marble Mar 14 '19 at 16:21

-

5

-

1@OrganicMarble I only skimmed it. Did anything in particular stand out for you beyond "uh yeah need more radiation shielding"? – Russell Borogove Mar 14 '19 at 17:25

-

2How much kg of food on average does an ISS astronaut consume per day? A ~year long mission this may actually be substantial for N people. That's my only outstanding thought after reading another of your awesome answers :). – Magic Octopus Urn Mar 14 '19 at 19:28

-

1@MagicOctopusUrn That and other consumables questions are addressed in the Bellcomm study. Not only did they plan to carry a year’s worth of freeze dried food, they planned to stow a year’s worth of solid waste... – Russell Borogove Mar 14 '19 at 20:13

-

2@RussellBorogove — there may come a time when I regret asking this question but... why did they plan to stow a year’s worth of solid waste? As opposed to just chucking it overboard? OK, maybe dry it out and reuse the moisture... jeez, I'm already regretting this... – Michael Lorton Mar 14 '19 at 20:40

-

3@Malvolio During Apollo, the waste was recovered so, in theory, it could be studied for biomedical concerns. I assume the reasoning was the similar here (except you'd obviously not return an entire year's worth of waste in the command module!). Another issue is that unless you give the waste a pretty strong push, it would drift along beside the ship for the entire flight, which besides being even less pleasant than stowing it, might interfere with star sightings, etc. – Russell Borogove Mar 14 '19 at 20:51

-

You didn't put anything in the fuel tank except some grid floors. Everything would have been dense-packed into the interstage and would only be unpacked into the former fuel tank in orbit. – Joshua Mar 14 '19 at 21:46

-

@Joshua The diagram actually shows webbing instead of grid floors. At any rate, that means the astronauts have to install plumbing, electrical conduit, etc, etc. Not impossible but definitely a lot of complexity. – Russell Borogove Mar 14 '19 at 21:58

-

Question: For the mass figures, does "tons" here mean US tons or does it mean metric tons, which should better be written "tonnes" or even more unambiguously "megagrams" (Mg)? It seems ambiguous because of the heavy use of metric units throughout this post, just don't know. – The_Sympathizer Mar 14 '19 at 23:10

-

5It's all megagrams/metric tons/tonnes. I've never gotten into the habit of the longer spelling, but I try to use metric units whenever possible. Most of my computations are back-of-the-envelope stuff where it doesn't matter that much which tons I'm using anyway ;) – Russell Borogove Mar 14 '19 at 23:15

-

2@The_Sympathizer Europeans tend to use ton for metric ton, rather than tonne :) – jwenting Mar 15 '19 at 05:28

-

1@jwenting : Ah, thanks. More reason I think why to just avoid any word that sounds or looks like "ton" and use Mg and megagram only, all the time. – The_Sympathizer Mar 15 '19 at 05:49

-

6

-

And hence I prefer to use 1000s of kilograms instead @RussellBorogove – jwenting Mar 15 '19 at 06:23

-

How close would they have been possible to fly by Venus? Maybe close enough to see the surface? – undefined Mar 15 '19 at 09:18

-

Getting there is not the problem. Getting back, however, is slightly more complicated than getting back from the moon. – Mast Mar 15 '19 at 13:48

-

5@undefined The dense clouds in venus atmosphere prevent seeing the surface from orbit. – Polygnome Mar 15 '19 at 17:07

-

How did you arrive at 31t of payload? After S-IVB's 2nd Burn (Translunar injection) the Saturn V put the entire 50t Apollo spacecraft on track to the moon... it would only need to burn the difference, 650m/s or so, to make it from there to Venus. Running 700m/s against 48.6t with a ISP of 421 gives ~40t of payload. I've also seen several sources that put a LEO to Venus transfer closer to 3.5km/s dV. I think the result is the same (it's totally unreasonable) I'm just not able to follow your math. – TemporalWolf Mar 15 '19 at 21:51

-

@undefined - That's why it's, "Risky, expensive and no point." - We have but only four CCCP probes to thank for the few pictures of Venus we have. – Mazura Mar 15 '19 at 22:11

-

1@TemporalWolf In your calculation, you're throwing away the mass of the S-IVB, then using the engine of the S-IVB for the burn. Figure another 14.1 tons for the S-IVB and instrument unit dry mass. – Russell Borogove Mar 15 '19 at 22:31

-

Even making those changes (ISP 312s for an AJ10-137 and 62.7t of starting mass) I'm unable to replicate those numbers. – TemporalWolf Mar 15 '19 at 22:39

-

1At no point are we throwing away the S-IVB; it's the habitable space for the mission. $m_0$ at TVI is 122.242t, $m_f$ is 48.081t. The service propulsion system isn't used for this maneuver (and is 2x LMDE instead of 1x AJ10 anyway). – Russell Borogove Mar 15 '19 at 22:44

-

1The 31t figure is "what is the mass of stuff that corresponds to the CSM+LM+SLA on an Apollo lunar mission"; the actual injected mass is 48t because we're keeping the 14 ton S-IVB and venting 3 tons of residual propellants. – Russell Borogove Mar 15 '19 at 22:49

-

Great answer! Regarding payload, I think of Apollo 8, which did a flyby of the Moon without carrying a lunar lander. They had a big tank instead. So Saturn V could easily carry extra fuel and supplies instead of the lander. – Andrew Breza Jul 18 '19 at 20:57

-

I took classes taught by Howard McCurdy in grad school. This answer reminds me of his firm belief that human spaceflight was more of a romantic notion than a practical necessity. He argued for more robots and fewer people in space exploration. – Andrew Breza Jul 18 '19 at 21:00