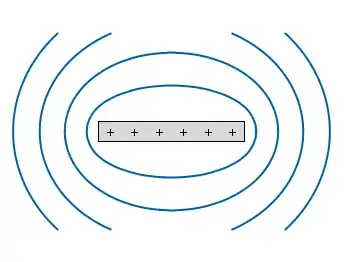

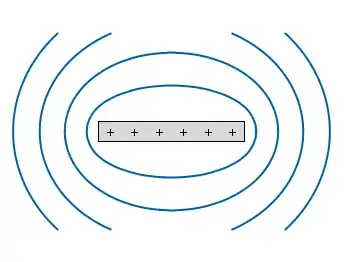

In the limiting case of arbitrary shape, there are bodies that have no "stable orbits", defined as simply repeating and not disrupted by infinitesimal perturbations. One example: The finite length rod:

(That's an E&M image, but gravitational potentials are the same shape). There is a repeating (circular) orbit around the "equator" of the rod (vertically oriented in the image above), but it's not stable against perturbations. Ditto for polar (over the "pole" of the rod) orbits. Trajectories at other inclinations are harder to analyze, but they don't obey anything that looks like Kepler's 1st law, and they don't have a simple periodic structure: In the limiting case of a very long rod, they're spirals up and down along it.

True, this is far from sphere+masscons, and hardly realistic (outside of science fiction). But a theory that says simpler bodies are certain to have stable orbits would have to have some way to indicate where it breaks down in the transition from the "simpler" geometry to this one. This is a high symmetry mass without high symmetry, stable orbits....

Edited to add more detail:

The article linked in the question is about orbits that are stable in the sense of "low orbits that don't crash into the Moon". But crashes are not generally the issue. For the TESS orbit, for example, stability is about not having to use lots of propellant to keep the desired orbital geometry. GEO communications satellites have to actively correct to stay at their designed latitude. Etc.

The bar example shows this. If you're trying to put something in a circular orbit around the "equator" of the bar at radius $R$, with the bar having mass $M$ and length $L$, the central force will be (see here for notation and a nice explanation of derivation; I've substituted $GM$ for $kQ$):

$F_\hat{r} = \frac{GM}{R\sqrt{R^2+(L/2)^2}} $

which in the usual way gives an orbital frequency of:

$ \omega_o^2 = \frac{GM}{R^2\sqrt{R^2+(L/2)^2}} $.

(As a check, that reduces to the Kepler's-law form $\omega_o^2 = GM/R^3$ when $R \gg L$)

That circular orbit definitely exists. But is it stable? To check, look at a perturbation along the rod (we'll return to velocity:radius perturbations later)

If you slightly-sideways-perturb a body in equatorial orbit around Earth, you can think of the resulting orbit as changing the inclination a little bit: The orbit spends half it's time north of the equator, half south, intersecting the original point twice per period. Putting it back just requires waiting until the right point, at most an orbital period, and applying the same-size perturbation.

But another way to think about this is that the satellite is executing harmonic motion around the original orbit. There's a restoring force because the $\hat{r}$ direction of the central force changes as the satellite moves north and south. You can derive the usual $\omega^2 = k/m$ form from

$F_\rm{restoring} = \frac{GMm}{R^2} sin(\theta) = \frac{GMm}{R^2} \frac{\Delta x}{R} $

leading to $\omega_p^2 = GM/R^3$, same as the orbital period: It goes up and down one per orbit, effectively just tiling the inclination, as we expected.

The rod is more complicated. The restoring force has the $L$ dependence from above (see here for the derivation):

$F_\rm{restoring} = \frac{GMm}{R^2 \sqrt{R^2+(L/2)^2}} \Delta x $

In close ($R<L$) orbits, the denominator is bigger, so there's less restoring force, so the period of oscillation is smaller. As a consequence, the amplitude of oscillation is bigger, making the satellite move further away from the idea orbit, but the orbit also doesn't repeat any more: You don't come back to the same place after one orbital period, so you can't really think of this as a tiny tilt to the orbit which you can correct back onto the same orbit after a while. Instead, the satellite is spiraling up and down along the bar, and may never come back to the same spot as the (projected) initial orbit. If you're goal was to orbit over some spot on the bar at some particular time of "day", this is a problem that's going to require lots of active correction to manage.

Velocity/height perturbations are unstable in the same sense. With a $1/R^2$ force, you get Kepler's elliptical repeating orbits where "eccentricity" is a useful idea. But when $R<L$ here, the force isn't as large, and a perturbed orbit doesn't close. Instead, it's apemajstro and perimajstro positions rotate around the bar with each orbit, and the effect on period is different from the Keplerian case.

Bottom line, once you get away from $1/R^2$ central forces, perturbations start to behave differently; whether that matters or not depends on your operational definition of stability.