In 1988, Intel introduced the 80386SX, most often referred to as the 386SX, a cut-down version of the 80386 with a 16-bit data bus mainly intended for lower-cost PCs aimed at the home, educational, and small-business markets, while the 386DX would remain the high-end variant used in workstations, servers, and other demanding tasks. The CPU remained fully 32-bit internally, but the 16-bit bus was intended to simplify circuit-board layout and reduce total cost. (From Wikipedia.)

So that indicates extra data lines were very expensive; the difference between a 386SX and 386DX computer came to hundreds of dollars. Okay. (The 8088 and 68008, and for that matter the 68000 itself, had likewise narrow data buses relative to the CPU internals, but in those cases maybe there were considerations like timely availability of support chips. The 386SX is the purest example, being developed and released three years after the full-width version of the chip.)

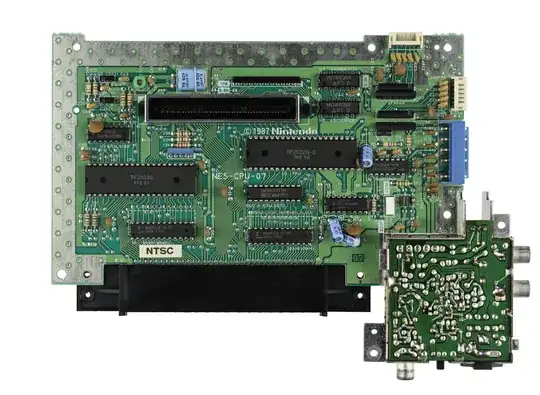

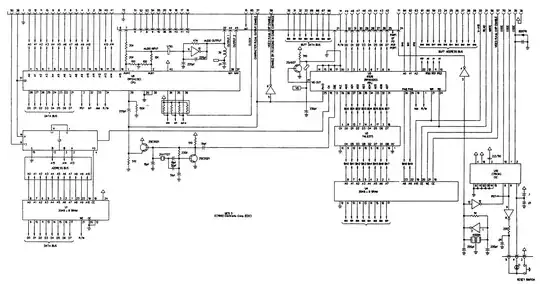

But hang on a minute. Take a look at the pinout of the NES cartridges: https://forums.nesdev.com/viewtopic.php?f=9&t=14924

The most remarkable feature, I think, is that it has an address and data bus (22 lines total) for the game program – and then a whole other address and data bus for fetching tile data. The point of that is clear: it provides double the bandwidth, lets the console fetch code and tiles simultaneously, allows higher quality graphics without having to provide extra RAM for caching tiles.

But if there was a problem with affording an extra sixteen lines in a $2000 PC in 1988, how on earth could Nintendo possibly afford to put an extra twenty-two lines, not only in a $200 console in 1983, but in every single cartridge? Okay the PC motherboard is a larger and more complex piece of kit, but that's going on two orders of magnitude difference in equipment cost, and five years difference in release date to boot.

How does that possibly make sense? Was Intel just engaging in market segmentation, or is there some technical consideration I am missing?