The Apollo Guidance Computer was used to control the command/service module and lunar module on the missions to the moon. (Definitely a retrocomputer!) As noted in this answer, programs were written in assembly language. There are several emulators available today, including one which can be run in a web browser.

Even though the AGC was invented before the C programming language, is a C compiler possible for this architecture? If not, why?

For the purposes of this question, a satisfactory compiler would support all of the C operators (including arithmetic, boolean, structure, and pointer) the original purpose of the AGC: notably, real-time signal processing and control. It does not have to be a lunar mission; the AGC was also used in a Navy rescue submarine and in the first airplane with computer fly-by-wire control.

Less important but nice to have:

- Originally I included structure and pointer operations as a requirement. However, arrays with indices would probably suffice.

- Ability to act as a general-purpose platform.

- Compliance to one or more standards (including but not limited to K&R, ANSI, and Embedded C).

- Floating point. The original software used fixed-point numbers, with subroutines for subtraction, multiplication, and division. Such numbers can be declared with Embedded C's

fixedtype. We'll call that good enough, even if it is possible to implement IEEE floating point. - Standard libraries or system calls (i.e. stdio should not be a concern).

The compiler would be hosted on another system, not on the AGC itself.

I hope these clarifications help!

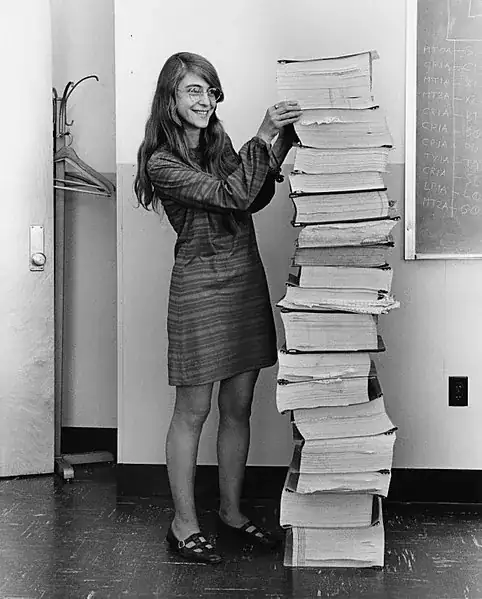

(Photograph of Apollo Director of Software Engineering Margaret Hamilton, next to the source code of her team)

8 * 12clocks. What currently-used microcontrollers are slower than the AGS, and for what kinds of computations? – Peter Cordes Sep 04 '18 at 09:054 (clock ratio) * 8 (mul cost) * 12 (clocks per subgroup on AGS) = 384clocks. Unless add/adc is complete garbage on PIC (for 16-bit integer add on an 8-bit CPU), it should be much faster. (I might be off by a factor of 4 for a pulse) – Peter Cordes Sep 04 '18 at 09:35