A bit hard to give a definitive answer as the term UNIX not only covers a huge variety of systems from early minis and microprocessors with a few KiB, to multi gigabyte 64 bit systems, but as well a huge range of more or less (usually less) compatible implementations. Even more, what to consider part of it? Especially the latter can be the defining moment for smaller system - which by default all early ones are. Does it need to have an IP stack, or a GUI? Which shell or editor?

A basic kernel with a few helpers (getty, shell, etc.) can already run in a few dozen KiB, even supporting multiple users. In fact, the very first implementations were as slim.

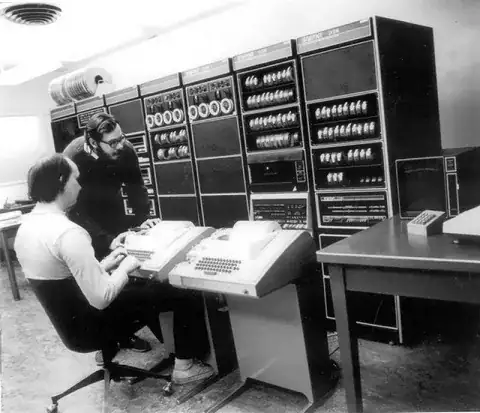

A good example for what a low end (non educational/research) system might be is Microsoft's XENIX. It's not an Unix-alike, but a fully licensed (*1) AT&T Unix. First based on genuine V7 sources, later upgraded to System III and System V. Microsoft sold it mostly to OEMs like Altos, Siemens or Tandy. A basic starter system may look like these:

Siemens PC-MX (~1981) an 8086-based multi-user system for up to 5 terminals (13 terminals possible), running at 8 MHz, 256KiB (up to 1 MiB possible) and a 10 MB HD. The later NS32K-based PC-MX2 brought already 1 MiB as minimum RAM. The system featured a special type of memory management. Siemens MX systems were the highest-selling Unix systems worldwide during the mid '80s to early '90s.

Tandy Model 16 (~1982) was essentially a Model II with a 68k subsystem running at 6 MHz fitted with 256 KiB and an 8 MiB HS. It could operate up to 9 terminals (DT-1). The Model 16 was in 1984/85 the best-selling Unix system in the US.

IBM PC-XT was gifted with SCO XENIX in 1983, requiring a basic 4.77 MHz 8088, 256 KiB RAM and a 10 MiB HD - although the manual mentions that some tools, like VI may need at least 384 KiB to run (*2). Also, while a PC-XT could run multi-user with terminals attached, it may not be as smooth :)) As a software package it dwarfed any other Unix sale in the US in numbers around 1986.

This may be as low as genuine Unix runs on a low-end microprocessor system - and being successful in real life applications.

*1 - Everything but the name.

*2 - PCjs shows nicely how Xenix felt on a 4.77 MHz 8088 with 640 KiB and 10 MiB HD :)