Do you have any citations for your claim that most MS-BASIC integer multiplication was done by turning into floats?

Beside having lived thru it, or noting that the source of MS-BASIC doesn't contain any integer routines (except for conversion)? (*1)

I assume the most simple and obvious proof would be to just try it. Commodore 8 bit machines are a great tool here as their BASIC provides access to a simple real time clock. The variable TI(ME) is incremented every 1/60th second. Since the effect is rather large, already a few seconds of measurement should deliver a valid result.

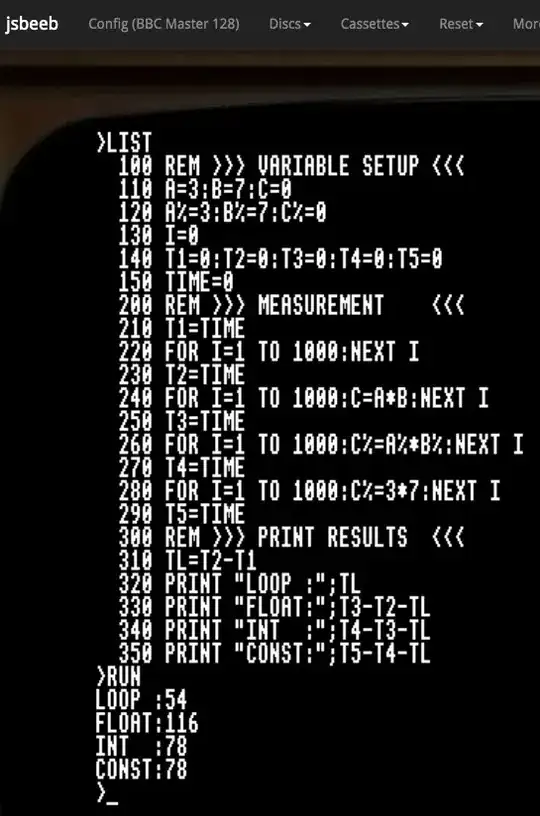

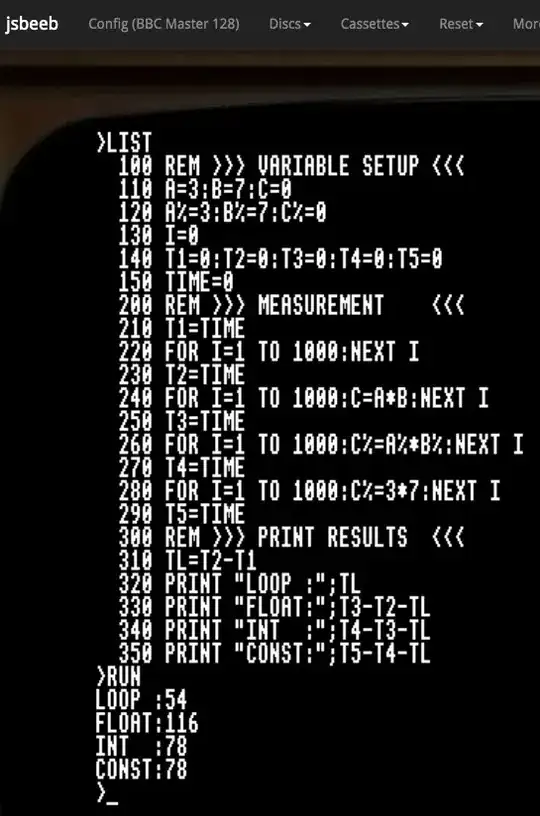

So lets setup a test program:

100 REM >>> VARIABLE SETUP <<<

110 A=3:B=7:C=0

120 A%=3:B%=7:C%=0

130 I=0

140 T1=0:T2=0:T3=0:T4=0:T5=0

150 TI$="000000"

200 REM >>> MEASUREMENT <<<

210 T1=TI

220 FOR I=1 TO 1000:NEXT I

230 T2=TI

240 FOR I=1 TO 1000:C=A*B:NEXT I

250 T3=TI

260 FOR I=1 TO 1000:C%=A%*B%:NEXT I

270 T4=TI

280 FOR I=1 TO 1000:C%=3*7:NEXT I

290 T5=TI

300 REM >>> PRINT RESULTS <<<

310 TL=T2-T1

320 PRINT "LOOP :";TL

330 PRINT "FLOAT:";T3-T2-TL

340 PRINT "INT :";T4-T3-TL

350 PRINT "CONST:";T5-T4-TL

Workings:

- The program defines 3 variables A, B and C as float and integer. A and B are preloaded with values (3; 7), while C is set to zero. This is done to have all variables ahead of used, so no allocation has to be done during use.

- TI is as well zeroed to avoid any overflow error (*2).

- A first time stamp is saved in T1.

- An empty loop is performed to measure the FOR/NEXT overhead.

- A time stamp is taken in T2

- The measurement for float calculation is done in form of multiplying 3 and 7 from variables a 1,000 (*3) times in a FOR...NEXT loop.

- A time stamp is saved in T3,

- followed by doing the same with integer variables and

- saving the time stamp in T4,

- followed doing the same with constant values and

- a final time stamp in T5.

Results are printed as difference between the time stamps (T1, T2, T3, T4, T5) for each test, reduced by the time taken for the empty loop.

While I suggest to try it on your own PET, CBM, C64 or C128, it will as well work on emulators. A great tool here could be the PET emulator at Masswerk. It's not only a fine implementation, but also offering a lot of ways for im-/export - including starting a program from a data URL, like with our test program:

Open this fine link to run above test program (maybe in another window)

Doing so should present a result similar to this:

LOOP : 91

FLOAT: 199

INT : 278

CONST: 275

The numbers show that using integer variables takes about 40% longer than doing so in float. This is simply due the fact that each and every integer value stored in any of the variables is converted to float before multiplication and the result converted back to integer. Interesting here is that the use of constants does not result any relevant speed up. Here again each constant has to be converted before used. In fact, converting from ASCII to float is even slower than converting from integer - but offset by skipping the need to search for each variable.

Speaking of variable lookup, it's well known, that that the sequence variables are defined in MS-BASIC, does have a huge influence on access time (*4). Swapping the definitions of float (line 110) and integer (line 120) variables does show this effect quite nice:

LOOP : 91

FLOAT: 218

INT : 259

CONST: 269

Now the integer malus has shrunk by the effect of variable access and allows us to calculate a close net cost of 30% overhead (259 vs 199 ticks) for type conversion when using integer instead of float.

Seeing as how the majority of processors before 80486DX (8,16 or 32 bit) didn't have any floating point processors, this would have been extremely slow.

Jau, it is. But there are good reasons to do so:

- Code size

Additional routines for integer multiply and divide would cost at least a few hundred bytes in code. This may not sound much, but keep in mind, that ROM storage was quite small and developers had to fight for every instruction. But beside the code for multiplication/division, it's even more about

- The way BASIC works

MS-BASIC is an interpretative language without any processing ahead of time. Inputted source code gets not prepared in any way beside turned into a more compact storage representation by using single byte symbols for keywords and operators. The method was called 'crunching' by Allen/Gates (*5), other called it tokenization. This process does not analyze any semantics. It's a literal representation of the source.

When the interpreter parses an expression it has no knowledge what type the elements are. Only if all are integer the calculation could be done using integer arithmetic. Thus it is mandatory to do all calculations in float, to avoid any intermediate rounding error (*6).

Of course, the cruncher could have been improved to leave hints to the interpreter, or even transform the expression into a format allowing to use integer operations wherever possible - but this would not only have meant to add a lot of code to already packed ROMs but as well increase RAM usage for BASIC code (*7). Something not really a good idea. After all, these interpreters were designed for machines with a basic RAM size as low as 4 KiB (PET, Apple II, TRS-80 M1, etc.).

So this again comes down to limited memory size of these computers.

And now for something complete different:

Chromatix did go the extra mile to port, modify and try above little test program for the BBC (or better Jsbeeb):

While not really asked for by the Question, I do think it's a worthwhile addition, showing how much a BASIC with proper integer support may gain from using them percent signs.

*1 - To be honest, it's simply much more fun to write some benchmark than simply looking up any old writing.

*2 - TI runs modulo 5,184,000 (24 * 60 * 60 * 60 ) i.e. is reset every 24 hours. Resetting it at the begin of the program will ensure no unintended reset will happen during measurement, thus simplifying calculation to subtraction. Except, TI can not be written, clearing is only possible via TI$. And yes, this destroys any time of day set before, but serious, noone cares for it's value on a PET outside of an application.

*3 - The number 1000 has been chosen to set run time close to 4-5 seconds per measurement. This will give a result large enough to gain valid data but still keep total run time below 30 seconds.

*4 - MS-BASIC stores variables (their structures) in sequence of definition. Lookup is done by sequential search. Thus access time is linear with position/sequence of definition.

*5 - The crunching code was written by Paul Allen.

*6 - Sure, it could start out with with integer and switch for using float as soon as any operation yields a fraction, or a float variable gets involved. Except, this might include backtracking the evaluation stack in case intermediate results (like from grouping by parentheses) exist, which would add even more code.

*7 - It's again important to keep in mind that the crunched BASIC code not only was a direct image of the source, but it must be possible to transform it back into it's source (or at least quite close) form. Reordering an expression is thus not an option - unless stored twice.