Why is ASCII this way?

First of all, there is no one best sorting order for everything. For example, should UPPER or lower case be first? Should numbers be before or after letters? Too many choices, and no way to please everyone. So they came up with specific pieces that "made sense":

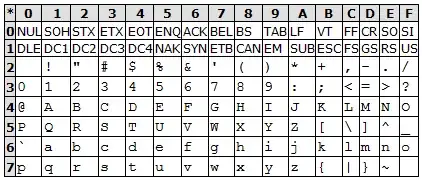

0x30–0x39 - Easy bit mask to get your integer value.

0x41–0x5A - Another easy bit mask to get your letter relative value. They could have started with 0x40, or put the space at the beginning. They ended up putting space at the beginning of all printable characters (0x20), which makes a lot of sense. So we ended up with @ at 0x40 - no specific logic to that particular character that I know of, but having something there and starting the letters at 0x41 makes sense to me for the times you need a placeholder of some sort to mark "right before the letters".

0x61–0x7a - Again a simple bit mask to get the letter relative value. Plus, if you want to turn UPPER into lower or vice versa, just flip one bit.

These could have been anywhere. But placing them at the beginning has the nice advantage that extensions to the character set - from 128 to 256 and beyond - can treat everything >= 0x20 as printable.

Everything else got filled in - 0x21–0x2f, 0x3a–0x3f, 0x5b–0x5f, 0x7b–0x7f. "Matching" characters generally next to each other, like ( and ), or with one character separating them, like < = > and [ \ ]. Most of the more universally used characters are earlier in the character set. The last character - 0x7f (delete or rubout) is another special case because it has all 7 bits set - see Delete character for all the gory details.

Why is C (and most other languages) this way?

A high-level language should be designed to be machine independent, or rather to make it possible to implement on different architectures with minimal changes. A language may be far more efficient on one architecture than another, but it should be possible to implement reasonably well on different architectures. A common example of this is Endianness, but another example is character sets. Most character sets - yes, even EBCDIC, do some logical grouping of letters and numbers. In the case of EBCDIC, the letters are in sequence, but lower case is before UPPER case and each alphabet is split into 3 chunks. So isalpha(), isalnum() and similar functions play a vital role. If you use (*c >= '0' && *c <= '9') || (*c >= 'A' && *c <= 'Z') || (*c >= 'a' && *c <= 'z') on an ASCII system it will be correct, but on an EBCDIC system it will not be correct - it will have quite a few False Positives. And while *c >= '0' && *c <= 'z' would have lots of False Positives in ASCII, it will totally fail in EBCDIC.

Arguably, a "perfect text sorting character set" could be created that would fit your "ideal", but it would inevitably be less-than-ideal for some other use. Every character set is a compromise.

isalnum(). And if you're implementingisalnum()on all but tiny-memory systems, you'd do well to use a lookup table -- so the call just turns into something likereturn tbl[ch] & (ISALPHA|ISDIGIT). – dave Jun 26 '19 at 12:09dd if=blah.ebcdic conv=ascii > blah.txtfor the unfortunate like me) and noticed those funky things about it as well. I've asked a similar question hoping to get some good insight on it. – Captain Man Jun 26 '19 at 16:08printf("£100");a compiler would generate a string containing all of the bytes that appeared in the source file between the first 0x22 byte and the next one, provided only that none of them was a 0x0A, 0x0D, 0x5C, or 0x3F. If £ was one byte in the source character set, the string would be four bytes long. If £ was two bytes, the string would be five bytes, but the compiler would't care that.... – supercat Jul 15 '22 at 17:02àrepresented as the three byte sequence 0x60, 0x08, 0x61 [grave, backspace, small a] which would appear as à on a typical dot matrix or daisy wheel printer. A compiler could accept in identifiers any bytes that have no other assigned meaning without having to know or care about how those bytes might be subdivided into glyphs. – supercat Jul 15 '22 at 17:04