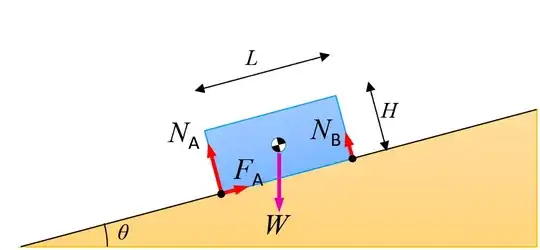

Is there an equation that gives you how the normal force is distributed? In particular, I am considering a basic example with a rectangular object at rest on an inclined plane. I think the biggest part of the normal force is applied at a distance down the incline from the center of mass of the object equal to the coefficient of friction times the distance between the object's center of mass and the surface. I think this case is basically 2D. How do you find a model of the different amounts of force between the object and the surface? Or if that is just really super complicated, how do you find the maximum amount of force at that point/line from 3 sentences ago, or at least what kind of math is used?

Also, please let me know if I am phrasing things poorly or if there would be a good source to learn about this.