To chime in on the issue. The overwhelming point here is:

1. It's commonplace that writing on the internet is just plain wrong.

The entire, total confusion here is that (as the OP rightly points out), clowns writing on the internet often refer to the Earth-Moon-Sun as being "in a line".

All the various confusion flows from that.

Note that even in the more-better article referred to in the top answer (with the excellent diagram), the same mistake is again made causing even more confusion.

2. "In a line" means "in" "a line" and can mean nothing else. Casual writers are unfamiliar with phrasing such as "a projection", etc.

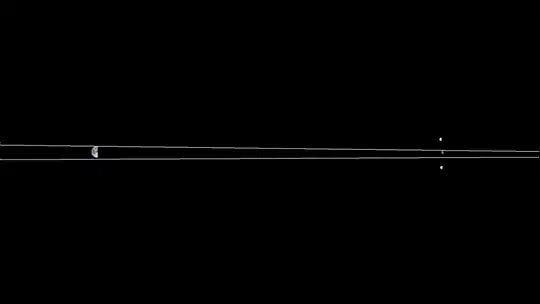

In the example below the three blue objects are of course not in a line.

"A line" is indicated by the yellow ... line.

It would be not unreasonable - but totally incorrect - to casually refer to them as being "in a line", particularly when the final one is spinning around. Of course, what you really mean is something like "it's come to the 'outside' of the 'circle'" or whatever. Quite simply, you're saying that "as seen from the top" they've become aligned.

Exactly as the OP enquires, when they are actually in a line - bingo, eclipse!

Other than that, extremely simply they are not in a line: bad writing.

To once again summarize, the OP points out that you can see stated, on the internet, in a zillion places that: "... the full moon appears when sun, moon and earth are in a straight line ..." but that sentence is, simply, wrong!