If you know where the center of mass is, the torque will be:

$$\boldsymbol{\tau}=\mathbf{R}\times\mathbf{W}$$

Where $\mathbf{R}$ is the vector from the hanging point that points to the center of mass and $\mathbf{W}$ is the weight vector pointing downward.

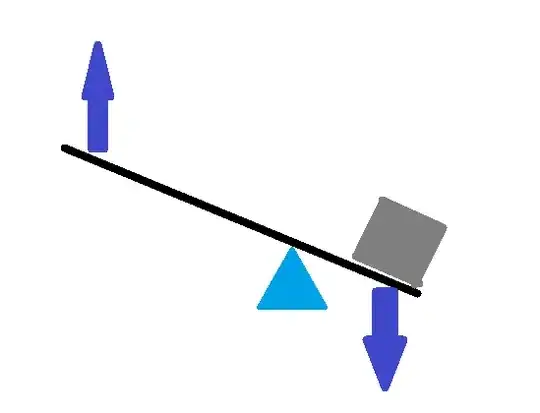

We conclude that the only possible arrangement for an equilibrium, here, is that the center of mass gets under the hanging point between the edge of the table and the end of the ruler.

This will make a self-regulating system. Which is the exactly the idea of a stable equilibrium.

If the system is pushed to any side, the torque will tend to pull the system back to its equilibrium state.

EDIT in response to the comment:

I usually prefer to talk less and let my math talk you you, as much as I can.

My approach was straight forward using the most compact relations. I specified the relative necessary place of the COM for the arrangement to be in equilibrium. And as gravity is only a constant, the It won't make any difference.

The only part I think requires a little thinking is how I came to the conclusion of where the COM must be. This is how:

If you rotate the system clockwise (relative to the picture provided.) the hanging point will be the tip of the ruler. So the COM must be to the left of it.

If the system rotates CCW, the COM will be the touching point off ruler and the edge of the table, so the COM must be to the right of the hanging point.

The only possible place for the COM to satisfy the conditions above is that its projection to the table be between the two hanging points about which we talked about. And it must be below the table to make an stable equilibrium.

If you want more reliable equilibriums, you should increase the torque. You can increase the mass of the system so that $\mathbf{W}$ increases.

The other two ways are increasing the angle between two vectors and increasing the lever arm. I can't claim certainly about these two because they effect each other.