Seeing as there isn't a colourimetry stackexchange, I'm asking here where a number of useful colourimetry topics have already been posted.

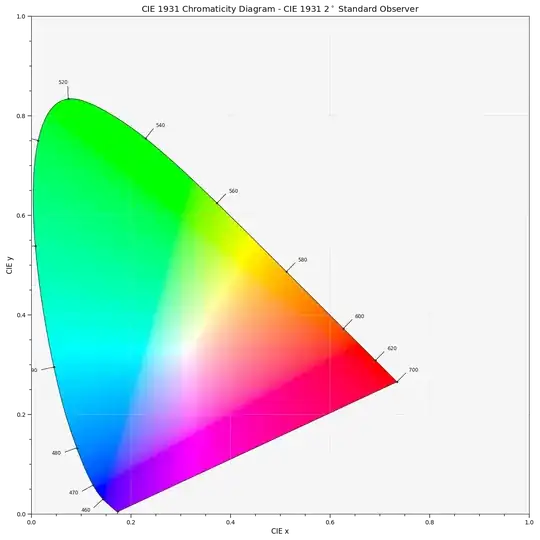

A number of excellent resources exist with regards to the ubiquitous CIE 1931 chromaticity diagram. This is noted to be the consequence of two consecutive projections, the first onto a 3D plane and the second onto a 2D surface. Also noted is the fact that the Y tristimulus value, corresponding to the CIE 1931 photopic observer, represents lightness due to the choices of the XYZ tristimulus values.

Despite the fact that the chromaticity diagram rigidly defines which colours are "real" and which are only imaginary, little explanation seems to exist for which values of Y (corresponding to which chromaticities) are valid.

For instance, this link seems to suggest that certain colours that appear to be in gamut will in fact be outside gamut at certain brightnesses.

Examination of David Macadam's paper "Maximum Visual Efficiency of Colored Materials" seems to suggest that there are indeed rigorous limits (Macadam limits) which relate to the illuminant under which the chromaticities are viewed. How exactly does this work?

In addition, I found this interesting claim in Billmeyer and Saltzmann's "Principles of Color Technology;"

Only colors of very low luminance factor, such as spectrum colors, can lie as far away from the illuminant axis as the spectrum locus; all other colors have lower purity. The lim- its within which all nonfluorescent reflecting colors must lie have been calculated (Rösch 1929; MacAdam 1935) and are shown projected onto the plane of the chromaticity diagram inFigure 4.28. They serve to outline the volume within which all real nonfluorescent colors lie. Although Rösch predates MacAdam, these limits are known as the MacAdam limits

This claim seems to be reflected on Bruce Lindbloom's diagram and the diagram included in Macadam's paper, in which luminosity drops to zero towards the spectral locus. Pure (or almost pure) spectral colours can be generated via a laser (or similar), and appear bright to the average observer. As such, to what do Billmeyer and Saltzmann refer when they suggest that spectral colours must inherently have a very low luminance factor? If this is the case, why is this low luminance (apparently inherent to pure spectral colours, and almost pure colours) capable of appearing subjectively bright?