EDIT, September 2014: I wrote to Prof. Ecalle, it turns out (as I had hoped) that the fractional iterates constructed by the recipe below really do come out $C^\infty,$ including a growth bound, in terms of $n,$ on the $n$-th derivatives at $0.$

The key word phrase is Gevrey Class. Also, I recently put a better exposition and example of the technique at https://math.stackexchange.com/questions/911818/how-to-get-fx-if-we-know-ffx-x2x/912324#912324

EDIT Feb. 2016: given that there is new discussion of this, i am pasting in the mathematical portion of Prof. Ecalle's reply, which includes the references

Yes, indeed, any $f(x)$ real analytic at $0$ and of the form

$$f(x)=x+ ax^{p+1} +o(x^{p+1}) \text{ for } a \not= 0\tag{$*$} $$

admits natural fractional iterates $g=f^{o w}$ (right or left of zero)

that are not just $C^\infty$ at $0$, but of Gevrey class $1/p$, i.e. with

bounds of type

$$| g^{(n)}(0)/n! |< c_0 \cdot c_1^n \cdot (n/p)! \tag{$**$}$$

Here, $g$ may denote any iterate of rational or real order $w$. You may

find details in my publication no 7 on my homepage

http://www.math.u-psud.fr/~ecalle/publi.html or again in publication

no 16 ("Six Lectures etc"; in English), pp 106-107 , Example 2 (with

$\nu=1$).

Here, Gevrey smoothness at $0$ results from $g(x^{1/p})$ being the Laplace

transform of an analytic function with (at worst) exponential growth

at infinity.

The "Six Lectures" are in Schlomiuk editor, 1993, Bifurcations and periodic orbits of vector fields / edited by Dana Schlomiuk. The reference is currently number 19 on Ecalle's web page, it reads:

Six Lectures on Transseries, Analysable Functions and the Constructive

Proof of Dulac's Conjecture . Bifurcations and Periodic Orbits of

Vector Fields, D. Schlomiuk ed., p.75-184, 1993, Kluwer

ORIGINAL: The correct answer to this belongs to the peculiar world of complex dynamics. See John Milnor, Dynamics in One Complex Variable.

First, an example. Begin with $f(z) = \frac{z}{1 + z},$ which has derivative $1$ at $z=0$ but, along the positive real axis, is slightly less than $x$ when $x > 0.$ We want to find a Fatou coordinate, which Milnor (page 107) denotes $\alpha,$ that is infinite at $0$ and otherwise solves what is usually called the Abel functional equation,

$$ \alpha(f(z)) = \alpha(z) + 1.$$

There is only one holomorphic Fatou coordinate up to an additive constant. We take

$$ \alpha(z)= \frac{1}{ z}.$$

To get fractional iterates $f_s(z)$ of $f(z),$ with real $0 \leq s \leq 1,$ we take

$$ f_s (z) = \alpha^{-1} \left( s + \alpha(z) \right) $$

and finally $$f_s(z) = \frac{z}{1 + s z}.$$

The desired semigroup homomorphism holds,

$$ f_s(f_t(z)) = f_{s + t}(z), $$

with $f_0(z) = z$ and $f_1(z) = f(z).$

Alright, the case of $\sin z$ emphasizing the positive real axis is not terribly different, as long as we restrict to the interval $ 0 < x \leq \frac{\pi}{2}.$ For any such $x,$ define

$x_0 = x, \; x_1 = \sin x, \; x_2 = \sin \sin x,$ and in general

$ x_{n+1} = \sin x_n.$ This sequence approaches $0$, and in fact does so for any $z$ in a certain open set around the interval $ 0 < x \leq \frac{\pi}{2}$ that is called a petal.

Now, given a specific $x$ with $x_1 = \sin x$ and $ x_{n+1} = \sin x_n$ it is a result of Jean Ecalle at Orsay that we may take

$$ \alpha(x) = \lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} \; \; \; \frac{3}{x_n^2} \; + \; \frac{6 \log x_n}{5} \; + \; \frac{79 x_n^2}{1050} \; + \; \frac{29 x_n^4}{2625} \; - \; n.$$

EDIT, August 2023: David Speyer has pointed out that the most direct expression of what Ecalle proved comes in

$$ \alpha(x) = \lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} \; \; \; \frac{3}{x_n^2} \; + \; \frac{6 \log x_n}{5}

\; - \; n.$$ I believe I included the $x_n^2, x_n^4$ terms because that was how I got the computer program (output below) to give small error ( the final column).

BACK to ORIGINAL

Note that $\alpha$ actually is defined on $ 0 < x < \pi$ with

$\alpha(\pi - x) = \alpha(x),$ but the symmetry also means that the inverse function returns to the interval $ 0 < x \leq \frac{\pi}{2}.$

Before going on, the limit technique in the previous paragraph is given in pages 346-353 of Iterative Functional Equations

by Marek Kuczma, Bogdan Choczewski, and Roman Ger. The solution is specifically Theorem 8.5.8 of subsection 8.5D, bottom of page 351 to top of page 353. Subsection 8.5A, pages 346-347, about Julia's equation, is part of the development.

As before, we define ( at least for $ 0 < x \leq \frac{\pi}{2}$) the parametrized interpolating functions,

$$ f_s (x) = \alpha^{-1} \left( s + \alpha(x) \right) $$

In particular

$$ f_{1/2} (x) = \alpha^{-1} \left( \frac{1}{2} + \alpha(x) \right) $$

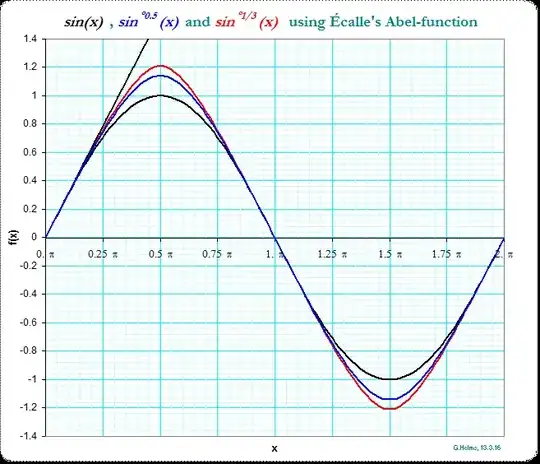

I calculated all of this last night. First, by the kindness of Daniel Geisler, I have a pdf of the graph of this at:

http://zakuski.math.utsa.edu/~jagy/sine_half.pdf

Note that we use the evident symmetries $ f_{1/2} (-x) = - f_{1/2} (x)$ and

$ f_{1/2} (\pi -x) = f_{1/2} (x)$

The result gives an interpolation of functions $f_s(x)$ ending at $ f_1(x)=\sin x$ but beginning at the continuous periodic sawtooth function, $x$ for $ -\frac{\pi}{2} \leq x \leq \frac{\pi}{2},$

then $\pi - x$ for $ \frac{\pi}{2} \leq x \leq \frac{3\pi}{2},$ continue with period $2 \pi.$

We do get $ f_s(f_t(z)) = f_{s + t}(z), $ plus the holomorphicity and symmetry of $\alpha$ show that

$f_s(x)$ is analytic on the full open interval $ 0 < x < \pi.$

EDIT, TUTORIAL: Given some $z$ in the complex plane in the interior of the equilateral triangle with vertices at $0, \sqrt 3 + i, \sqrt 3 - i,$ take $z_0 = z, \; \; z_1 = \sin z, \; z_2 = \sin \sin z,$ in general $z_{n+1} = \sin z_n$ and $z_n = \sin^{[n]}(z).$ It does not take long to show that $z_n$ stays within the triangle, and that $z_n \rightarrow 0$ as $n \rightarrow \infty.$

Second, say $\alpha(z)$ is a true Fatou coordinate on the triangle,

$\alpha(\sin z) = \alpha(z) + 1,$ although we do not know any specific value.

Now, $\alpha(z_1) - 1 = \alpha(\sin z_0) - 1 = \alpha(z_0) + 1 - 1 = \alpha(z_0).$ Also

$\alpha(z_2) - 2 = \alpha(\sin(z_1)) - 2 = \alpha(z_1) + 1 - 2 = \alpha(z_1) - 1 = \alpha(z_0).$

Induction, given $\alpha(z_n) - n = \alpha(z_0),$ we have

$\alpha(z_{n+1}) - (n+1) = \alpha(\sin z_n) - n - 1 = \alpha(z_n) + 1 - n - 1 = \alpha(z_0).$

So, given $z_n = \sin^{[n]}(z),$ we have $\alpha(z_n) - n = \alpha(z).$

Third , let

$L(z) = \frac{3}{z^2}+ \frac{6 \log z}{5} + \frac{79 z^2}{ 1050} + \frac{29 z^4}{2625}$.

This is a sort of asymptotic expansion (at 0) for $\alpha(z),$ the error is

$| L(z) - \alpha(z) | < c_6 |z|^6.$

It is unlikely that putting more terms on $L(z)$ leads to a convergent series, even in the triangle.

Fourth, given some $ z =z_0$ in the triangle. We know that $z_n \rightarrow 0$.

So $| L(z_n) - \alpha(z_n) | < c_6 |z_n|^6.$ Or

$| (L(z_n) - n ) - ( \alpha(z_n) - n) | < c_6 |z_n|^6 ,$ finally

$$ | (L(z_n) - n ) - \alpha(z) | < c_6 |z_n|^6 .$$

Thus the limit being used is appropriate.

Fifth, there is a bootstrapping effect in use. We have no actual value for $\alpha(z),$ but we can write a formal power series for the solution of a Julia equation for

$\lambda(z) = 1 / \alpha'(z),$ that is $\lambda(\sin z ) = \cos z \; \lambda(z).$ The formal power series for $\lambda(z)$ begins (KCG Theorem 8.5.1) with $- z^3 / 6,$ the first term in the power series of $\sin z$ after the initial $z.$ We write several more terms,

$$\lambda(z) \asymp - \frac{z^3}{6} - \frac{z^5}{30} - \frac{41 z^7}{3780} - \frac{4 z^9}{945} \cdots.$$

We find the formal reciprocal,

$$\frac{1}{\lambda(z)} = \alpha'(z) \asymp -\frac{6}{z^3} + \frac{6}{5 z} + \frac{79 z}{525} + \frac{116 z^3}{2625} + \frac{91543 z^5}{6063750} + \cdots.$$

Finally we integrate term by term,

$$\alpha(z) \asymp \frac{3}{z^2} + \frac{6 \log z }{5} + \frac{79 z^2}{1050} + \frac{29 z^4}{2625} + \frac{91543 z^6}{36382500} + \cdots.$$

and truncate where we like,

$$\alpha(z) = \frac{3}{z^2} + \frac{6 \log z }{5} + \frac{79 z^2}{1050} + \frac{29 z^4}{2625} + O(z^6)$$

Numerically, let me give some indication of what happens, in particular to emphasize

$ f_{1/2} (\pi/2) = 1.140179\ldots.$

x alpha(x) f(x) f(f(x)) sin x f(f(x))- sin x

1.570796 2.089608 1.140179 1.000000 1.000000 1.80442e-11

1.560796 2.089837 1.140095 0.999950 0.999950 1.11629e-09

1.550796 2.090525 1.139841 0.999800 0.999800 1.42091e-10

1.540796 2.091672 1.139419 0.999550 0.999550 3.71042e-10

1.530796 2.093279 1.138828 0.999200 0.999200 1.97844e-10

1.520796 2.095349 1.138070 0.998750 0.998750 -2.82238e-10

1.510796 2.097883 1.137144 0.998201 0.998201 -7.31867e-10

1.500796 2.100884 1.136052 0.997551 0.997551 -1.29813e-09

1.490796 2.104355 1.134794 0.996802 0.996802 -1.14504e-09

1.480796 2.108299 1.133372 0.995953 0.995953 9.09416e-11

1.470796 2.112721 1.131787 0.995004 0.995004 1.57743e-09

1.460796 2.117625 1.130040 0.993956 0.993956 5.63618e-10

1.450796 2.123017 1.128133 0.992809 0.992809 -3.00337e-10

1.440796 2.128902 1.126066 0.991562 0.991562 1.19926e-09

1.430796 2.135285 1.123843 0.990216 0.990216 2.46512e-09

1.420796 2.142174 1.121465 0.988771 0.988771 -2.4357e-10

1.410796 2.149577 1.118932 0.987227 0.987227 -1.01798e-10

1.400796 2.157500 1.116249 0.985585 0.985585 -1.72108e-10

1.390796 2.165952 1.113415 0.983844 0.983844 -2.31266e-10

1.380796 2.174942 1.110434 0.982004 0.982004 -4.08812e-10

1.370796 2.184481 1.107308 0.980067 0.980067 1.02334e-09

1.360796 2.194576 1.104038 0.978031 0.978031 3.59356e-10

1.350796 2.205241 1.100627 0.975897 0.975897 2.36773e-09

1.340796 2.216486 1.097077 0.973666 0.973666 -1.56162e-10

1.330796 2.228323 1.093390 0.971338 0.971338 -5.29822e-11

1.320796 2.240766 1.089569 0.968912 0.968912 8.31102e-10

1.310796 2.253827 1.085616 0.966390 0.966390 -2.91373e-10

1.300796 2.267522 1.081532 0.963771 0.963771 -5.45974e-10

1.290796 2.281865 1.077322 0.961055 0.961055 -1.43066e-10

1.280796 2.296873 1.072986 0.958244 0.958244 -1.58642e-10

1.270796 2.312562 1.068526 0.955336 0.955336 -3.14188e-10

1.260796 2.328950 1.063947 0.952334 0.952334 3.20439e-10

1.250796 2.346055 1.059248 0.949235 0.949235 4.32107e-10

1.240796 2.363898 1.054434 0.946042 0.946042 1.49412e-10

1.230796 2.382498 1.049505 0.942755 0.942755 3.42659e-10

1.220796 2.401878 1.044464 0.939373 0.939373 4.62813e-10

1.210796 2.422059 1.039314 0.935897 0.935897 3.63659e-11

1.200796 2.443066 1.034056 0.932327 0.932327 3.08511e-09

1.190796 2.464924 1.028693 0.928665 0.928665 -8.44918e-10

1.180796 2.487659 1.023226 0.924909 0.924909 6.32892e-10

1.170796 2.511298 1.017658 0.921061 0.921061 -1.80822e-09

1.160796 2.535871 1.011990 0.917121 0.917121 3.02818e-10

1.150796 2.561407 1.006225 0.913089 0.913089 -3.52346e-10

1.140796 2.587938 1.000365 0.908966 0.908966 9.35707e-10

1.130796 2.615498 0.994410 0.904752 0.904752 -2.54345e-10

1.120796 2.644121 0.988364 0.900447 0.900447 -6.20484e-10

1.110796 2.673845 0.982228 0.896052 0.896052 -7.91102e-10

1.100796 2.704708 0.976004 0.891568 0.891568 -1.62699e-09

1.090796 2.736749 0.969693 0.886995 0.886995 -5.2244e-10

1.080796 2.770013 0.963297 0.882333 0.882333 -8.63283e-10

1.070796 2.804543 0.956818 0.877583 0.877583 -2.85301e-10

1.060796 2.840386 0.950258 0.872745 0.872745 -1.30496e-10

1.050796 2.877592 0.943618 0.867819 0.867819 -2.82645e-10

1.040796 2.916212 0.936899 0.862807 0.862807 8.81083e-10

1.030796 2.956300 0.930104 0.857709 0.857709 -7.70554e-10

1.020796 2.997914 0.923233 0.852525 0.852525 1.0091e-09

1.010796 3.041114 0.916288 0.847255 0.847255 -4.96194e-10

1.000796 3.085963 0.909270 0.841901 0.841901 6.71018e-10

0.990796 3.132529 0.902182 0.836463 0.836463 -9.28187e-10

0.980796 3.180880 0.895023 0.830941 0.830941 -1.45774e-10

0.970796 3.231092 0.887796 0.825336 0.825336 1.26379e-09

0.960796 3.283242 0.880502 0.819648 0.819648 -1.84287e-10

0.950796 3.337412 0.873142 0.813878 0.813878 5.84829e-10

0.940796 3.393689 0.865718 0.808028 0.808028 -2.81364e-10

0.930796 3.452165 0.858230 0.802096 0.802096 -1.54149e-10

0.920796 3.512937 0.850679 0.796084 0.796084 -8.29982e-10

0.910796 3.576106 0.843068 0.789992 0.789992 3.00744e-10

0.900796 3.641781 0.835396 0.783822 0.783822 8.10903e-10

0.890796 3.710076 0.827666 0.777573 0.777573 -1.23505e-10

0.880796 3.781111 0.819878 0.771246 0.771246 5.31326e-10

0.870796 3.855015 0.812033 0.764842 0.764842 2.26584e-10

0.860796 3.931924 0.804132 0.758362 0.758362 3.97021e-10

0.850796 4.011981 0.796177 0.751806 0.751806 -7.84946e-10

0.840796 4.095339 0.788168 0.745174 0.745174 -3.03503e-10

0.830796 4.182159 0.780107 0.738469 0.738469 2.63202e-10

0.820796 4.272614 0.771994 0.731689 0.731689 -7.36693e-11

0.810796 4.366886 0.763830 0.724836 0.724836 -1.84604e-10

0.800796 4.465171 0.755616 0.717911 0.717911 3.22084e-10

0.790796 4.567674 0.747354 0.710914 0.710914 -2.93204e-10

0.780796 4.674617 0.739043 0.703845 0.703845 1.58448e-11

0.770796 4.786234 0.730686 0.696707 0.696707 -8.89497e-10

0.760796 4.902777 0.722282 0.689498 0.689498 2.40592e-10

0.750796 5.024513 0.713833 0.682221 0.682221 -3.11017e-10

0.740796 5.151728 0.705339 0.674876 0.674876 7.32554e-10

0.730796 5.284728 0.696801 0.667463 0.667463 -1.73919e-10

0.720796 5.423842 0.688221 0.659983 0.659983 -1.66422e-10

0.710796 5.569419 0.679599 0.652437 0.652437 5.99509e-10

0.700796 5.721838 0.670935 0.644827 0.644827 -2.45424e-10

0.690796 5.881501 0.662231 0.637151 0.637151 -6.29884e-10

0.680796 6.048843 0.653487 0.629412 0.629412 1.86262e-10

0.670796 6.224333 0.644704 0.621610 0.621610 -5.04285e-10

0.660796 6.408471 0.635883 0.613746 0.613746 -6.94697e-12

0.650796 6.601802 0.627025 0.605820 0.605820 -3.81152e-10

0.640796 6.804910 0.618129 0.597834 0.597834 4.10222e-10

0.630796 7.018428 0.609198 0.589788 0.589788 -1.91816e-10

0.620796 7.243040 0.600231 0.581683 0.581683 -4.90592e-10

0.610796 7.479486 0.591230 0.573520 0.573520 4.29742e-10

0.600796 7.728570 0.582195 0.565300 0.565300 -1.38719e-10

0.590796 7.991165 0.573126 0.557023 0.557023 -4.05081e-10

0.580796 8.268218 0.564025 0.548690 0.548690 -5.76379e-10

0.570796 8.560763 0.554892 0.540302 0.540302 1.49155e-10

0.560796 8.869925 0.545728 0.531861 0.531861 1.0459e-11

0.550796 9.196935 0.536533 0.523366 0.523366 -1.15537e-10

0.540796 9.543137 0.527308 0.514819 0.514819 -2.84462e-10

0.530796 9.910004 0.518054 0.506220 0.506220 6.24335e-11

0.520796 10.299155 0.508771 0.497571 0.497571 -9.24078e-12

0.510796 10.712365 0.499460 0.488872 0.488872 8.29491e-11

0.500796 11.151592 0.490122 0.480124 0.480124 3.31769e-10

0.490796 11.618996 0.480757 0.471328 0.471328 2.27307e-10

0.480796 12.116964 0.471366 0.462485 0.462485 3.06434e-10

0.470796 12.648140 0.461949 0.453596 0.453596 4.77846e-11

0.460796 13.215459 0.452507 0.444662 0.444662 1.53162e-10

0.450796 13.822186 0.443041 0.435682 0.435682 -2.87541e-10

0.440796 14.471963 0.433551 0.426660 0.426660 -5.20332e-11

0.430796 15.168860 0.424037 0.417595 0.417595 -8.17951e-11

0.420796 15.917436 0.414501 0.408487 0.408487 -4.6788e-10

0.410796 16.722816 0.404944 0.399340 0.399340 3.70729e-10

0.400796 17.590771 0.395364 0.390152 0.390152 -6.97547e-11

0.390796 18.527825 0.385764 0.380925 0.380925 -2.45522e-10

0.380796 19.541368 0.376143 0.371660 0.371660 4.09758e-10

0.370796 20.639804 0.366503 0.362358 0.362358 1.15221e-10

0.360796 21.832721 0.356843 0.353019 0.353019 -4.75977e-11

0.350796 23.131092 0.347165 0.343646 0.343646 -4.27696e-10

0.340796 24.547531 0.337468 0.334238 0.334238 2.12743e-10

0.330796 26.096586 0.327755 0.324796 0.324796 4.06133e-10

0.320796 27.795115 0.318024 0.315322 0.315322 -2.71476e-10

0.310796 29.662732 0.308276 0.305817 0.305817 -3.74988e-10

0.300796 31.722372 0.298513 0.296281 0.296281 -1.50491e-10

0.290796 34.000986 0.288734 0.286715 0.286715 2.17798e-11

0.280796 36.530413 0.278940 0.277121 0.277121 4.538e-10

0.270796 39.348484 0.269132 0.267499 0.267499 5.24261e-11

0.260796 42.500432 0.259311 0.257850 0.257850 7.03059e-11

0.250796 46.040690 0.249475 0.248175 0.248175 -1.83863e-10

0.240796 50.035239 0.239628 0.238476 0.238476 4.06119e-10

0.230796 54.564668 0.229768 0.228753 0.228753 -2.56253e-10

0.220796 59.728239 0.219896 0.219007 0.219007 -7.32657e-11

0.210796 65.649323 0.210013 0.209239 0.209239 3.43103e-11

0.200796 72.482783 0.200120 0.199450 0.199450 -1.20351e-10

0.190796 80.425131 0.190216 0.189641 0.189641 1.07544e-10

0.180796 89.728726 0.180303 0.179813 0.179813 9.93221e-11

0.170796 100.721954 0.170380 0.169967 0.169967 2.63903e-10

0.160796 113.838454 0.160449 0.160104 0.160104 6.74095e-10

0.150796 129.660347 0.150510 0.150225 0.150225 4.34057e-10

0.140796 148.983681 0.140563 0.140332 0.140332 -2.90965e-11

0.130796 172.920186 0.130610 0.130424 0.130424 4.02502e-10

0.120796 203.060297 0.120649 0.120503 0.120503 -1.85618e-11

0.110796 241.743576 0.110683 0.110570 0.110570 4.2044e-11

0.100796 292.525678 0.100711 0.100626 0.100626 -1.73504e-11

0.090796 361.023855 0.090734 0.090672 0.090672 2.88887e-10

0.080796 456.537044 0.080752 0.080708 0.080708 -2.90848e-10

0.070796 595.371955 0.070767 0.070737 0.070737 4.71103e-10

0.060796 808.285844 0.060778 0.060759 0.060759 -3.90636e-10

0.050796 1159.094719 0.050785 0.050774 0.050774 3.01403e-11

0.040796 1798.677124 0.040791 0.040785 0.040785 3.77092e-10

0.030796 3159.000053 0.030794 0.030791 0.030791 2.4813e-10

0.020796 6931.973789 0.020796 0.020795 0.020795 2.95307e-10

0.010796 25732.234731 0.010796 0.010796 0.010796 1.31774e-10

x alpha(x) f(x) f(f(x)) sin x f(f(x))- sin x