(This is not an answer, but an extensive comment and numerical simulation about Grundy values.)

I believe there is some level of confusion because there are actually two very similar games under discussion: in what I propose to call the original game, the moves from any $n>1$ are to $n+1$ and $n/p$ with $p$ a prime factor of $n$, whereas in the modified game (suggested in the comments to the question), the only move from a prime $p$ is to $1$ (in both cases, there are no move from $1$, making whoever reaches $1$ first the winner).

The original game is not well-founded, so it conceivably has drawing positions, but as proved in the original question, there are actually no such positions; the modiified game, however, is well-founded. Furthermore, the P (=second player wins) and N (=first player wins) positions for both games coincide, so we can treat them as identical insofar as studying the P/N positions go. However, this remark does not extend to the Grundy function (nim value, or whatever you might want to call it): in the modified game, the Grundy value of any prime number is $1$ by definition; in the original game, there is no reason for this to be the case.

It is not clear a priori that the Grundy value is always finite/meaningful in the original game, because it has a loopy component: while it was proved in the question that $G$ is never a draw under perfect play, I don't see an obvious reason why $G + (*n)$ might not be a draw. For explanations as to what Grundy values mean in the case of loopy game, I refer to A. Siegel, Combinatorial Game Theory (2013), definition IV.4.12 (not exactly applicable here because the game isn't finite either, but if we believe figure 4.7 in the definition it doesn't matter). The gist of the matter is that $G$ is said to have Grundy value $n$ iff $G + (*n)$ (meaning the disjunctive sum of $G$ and a single nim heap with $n$ sticks) is a second-player win (viꝫ. is a P position): so long as all options of $G$ have a finite Grundy value, it is also the case that $G$ does, and the Grundy value of $G$ is then given by the mex (=smallest excluded) of the Grundy values of the options; when this is the case, $G + (*n)$ also have a finite Grundy value, given by the nim sum as usual. Loopy games can conceivably have non-finite Grundy values (which Siegel writes $\infty(S)$ where $S$ is a set), but experimentally this does not occur for the game being discussed here. (I don't have a proof. Of course I'm talking about the original game here, because in the case of the modified game, this issue doesn't arise at all.)

The following Sage code computes the Grundy value of the position $n$ in either the original or the modified game according to the value of the variable modified_game (the computation is straightforward after noting the fact that P-positions have Grundy value 0, even in loopy games; the fact that the code terminates proves that the computed value is finite):

# Compute the Grundy function of the following game: from n>1 we can

# move to either n+1 or n/p where p is a prime factor of n (and n=1

# there are no legal moves: whoever reaches 1 first wins the game).

See <URL:

https://mathoverflow.net/questions/445015/a-little-number-theoretic-game

> for context and discussion.

Set the following to False for the original game, and True for the

variant where the only allowed move from p prime is to move to 1

(i.e., win).

modified_game = False

Warning: Be sure to clear cache_grundy if this is changed!

Return list of possible moves from n, in sorted order

def moves(n):

if n==1:

return []

return sorted([n+1] + [n/p for (p,_) in factor(n)])

cache_pn = {}

def compute_pn(n):

# Return True if the position is P or False if it is N

if n in cache_pn: return cache_pn[n]

if modified_game and is_prime(n):

# This shouldn't change anything:

cache_pn[n]=False

return False

for k in moves(n):

if compute_pn(k):

# We have a P option: the position is N

cache_pn[n]=False

return False

# Every option is N: the position is P

cache_pn[n]=True

return True

cache_grundy = {}

def compute_grundy(n):

# Return the Grundy value of the position n

if n in cache_grundy: return cache_grundy[n]

if compute_pn(n):

# We treat P positions as a special case to avoid looping

# forever (note that even for loopy games, the Grundy value of

# a second-player win is unambiguously 0).

cache_grundy[n] = 0

return 0

if modified_game and is_prime(n):

# In the modified game, prime numbers have Grundy value 1 by definition

cache_grundy[n]=1

return 1

# Compute the set of excluded values:

excl = set()

for k in moves(n):

excl.add(compute_grundy(k))

# Now return its mex:

for v in range(len(excl)+1):

if not v in excl:

cache_grundy[n] = v

return v

raise Exception("this should not happen")

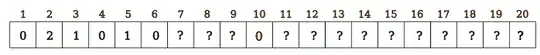

The first Grundy values for the original game, starting with 1 are: 0, 2, 1, 0, 1, 0, 2, 1, 2, 0, 1, 2, 1, 0, 2, 0, 2, 1, 2, 1, 3, 0, 1, 3, 0, 3, 0, 1, 2, 1.

The corresponding values for the modified game are as follows: 0, 1, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 1, 2, 0, 1, 2, 1, 0, 2, 0, 1, 3, 1, 1, 2, 0, 1, 3, 0, 2, 0, 2, 1, 3.

The first P positions for either game are: 1, 4, 6, 10, 14, 16, 22, 25, 27, 34, 36, 38, 40, 46, 49, 51, 56, 58, 60, 63, 65, 69, 74, 77, 82, 84, 86, 88, 91, 94, 96, 100, 104, 106, 111, 115, 117, 119, 121, 123, 129, 132, 134, 136, 140, 142, 144, 146, 150, 152.

The first positions having the following Grundy values in the original game are: 0: 1; 1: 3; 2: 2; 3: 21; 4: 78; 5: 5538; 6: 138600. No position up to $10^7$ has Grundy value greater than 6. Edit: the number 32110722 ($2 × 3^3 × 7 × 17 × 19 × 263$) is the first with Grundy value 7.

The corresponding values for the modified game are: 0: 1; 1: 2; 2: 9; 3: 18; 4: 364; 5: 1260; 6: 108108. No position up to $10^7$ has Grundy value greater than 6. Edit: the number 23129820 ($2^2 × 3^3 × 5 × 7 × 29 × 211$) is the first with Grundy value 7.

The tally of positions among the first $10^7$ having the following Grundy values in the original game are: 0: 3261996; 2: 2030150; 1: 3203496; 3: 1224407; 4: 258511; 5: 21142; 6: 297.

The tally of positions among the first $10^7$ having the following Grundy values in the modified game are: 0: 3261996; 1: 3390181; 2: 1978115; 3: 1105840; 4: 242523; 5: 20995; 6: 349.

(So the discrepancy between the counts found by I. J. Kennedy and Peter Taylor is explained by the fact that one was considering the original game and one was considering the modified game. I hope this clears up the confusion!)

Update (2023-04-21): Besides the Grundy value, I think it's also interesting to consider the “game duration” (I don't know the standard term for this), namely the number of moves in the game if the winning player tries to win as fast as possible while the losing player tries to lose as slowly as possible. This is defined inductively by:

$$

\begin{aligned}

\operatorname{duration}(G) &= 0\text{ if $G$ is terminal}\\

\operatorname{duration}(G) &= \max\{\operatorname{duration}(G')+1 : G'\text{ option of }G\}\\

&\text{ if $G$ is a P-position}\\

\operatorname{duration}(G) &= \min\{\operatorname{duration}(G')+1 : G'\text{ a P-option of }G\}\\

&\text{ if $G$ is an N-position}\\

\end{aligned}

$$

and Sage code computing it is as follows (continuing the code already written above):

cache_duration = {}

def compute_duration(n):

# Return the game duration of the position n (where the losing

# player tries to make the game last for as long as possible

# whereas the winning player tries to end it as soon as possible).

if n in cache_duration: return cache_duration[n]

if n==1:

cache_duration[n]=0

return 0

if is_prime(n):

cache_duration[n]=1

return 1

if compute_pn(n):

# We are the losing player: try to delay!

vals = [compute_duration(k)+1 for k in moves(n)]

dur = max(vals)

cache_duration[n] = dur

return dur

else:

# We are the winning player: try to end!

vals = [compute_duration(k)+1 for k in moves(n) if compute_pn(k)]

dur = min(vals)

cache_duration[n] = dur

return dur

(clearly this is the same for the original game and for the modified game since from a prime position the player will immediately move to 1 and terminate the game). Note that the game duration thus defined is even for P-positions and odd for N-positions, so it contains the information of which player is winning.

The first duration values for the game, starting with 1 are: 0, 1, 1, 2, 1, 2, 1, 3, 3, 2, 1, 3, 1, 6, 5, 4, 1, 3, 1, 3, 3, 2, 1, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 1, 3, 1, 5, 7, 6, 5, 4, 1, 6, 5, 4, 1, 3, 1, 3, 3, 2, 1, 5, 4, 3.

The first positions having the following durations in the game are: 0: 1; 1: 2; 2: 4; 3: 8; 4: 16; 5: 15; 6: 14; 7: 24; 8: 74; 9: 93; 10: 142; 11: 141; 12: 140; 13: 622; 14: 745; 15: 1204; 16: 1203; 17: 1202; 18: 1935; 19: 1934; 20: 7216; 21: 7215; 22: 7214; 23: 12847; 24: 21643; 25: 33539; 26: 86611; 27: 86610; 28: 86609; 29: 281331; 30: 281330; 31: 449631; 32: 562675; 33: 562674; 34: 1221050; 35: 2517976; 36: 2517975; 37: 5845198; 38: 8439912; 39: 8439911; 40: 8439910.

The tally of positions among the first $10^7$ having the following durations in the game are: 0: 1; 1: 664579; 2: 30657; 3: 629716; 4: 206897; 5: 1205915; 6: 378438; 7: 1318956; 8: 680231; 9: 1200304; 10: 779015; 11: 818601; 12: 572977; 13: 467615; 14: 324556; 15: 237032; 16: 161209; 17: 110655; 18: 73592; 19: 49266; 20: 32225; 21: 20968; 22: 13227; 23: 8755; 24: 5537; 25: 3515; 26: 2192; 27: 1420; 28: 825; 29: 476; 30: 285; 31: 153; 32: 91; 33: 51; 34: 30; 35: 22; 36: 9; 37: 3; 38: 1; 39: 1; 40: 1.

For example, here's how the game unfolds starting from 8439910 (in 40 moves):

A: 8439911; B: 8439912; A: 8439913; B: 8439914; A: 4219957; B: 4219958; A: 4219959; B: 1406653; A: 1406654; B: 1406655; A: 281331; B: 93777; A: 93778; B: 93779; A: 93780; B: 93781; A: 93782; B: 7214; A: 7215; B: 7216; A: 7217; B: 7218; A: 3609; B: 1203; A: 1204; B: 1205; A: 1206; B: 603; A: 201; B: 202; A: 203; B: 204; A: 205; B: 206; A: 207; B: 69; A: 70; B: 10; A: 11; B: 1 (wins)