Nearly every mathematician nowadays is familiar with the fact that there is up to isomorphism only one complete ordered field, the real numbers.

Theorem. Any two complete ordered fields are isomorphic.

Proof. $\newcommand\Q{\mathbb{Q}}\newcommand\R{\mathbb{R}}$Let us observe first that every complete ordered field $R$ is Archimedean, which means that there is no number in $R$ that is larger than every finite sum $1+1+\cdots+1$. If there were such a number, then by completeness, there would have to be a least such upper bound $b$ to these sums; but $b-1$ would also be an upper bound, which is a contradiction. So every complete ordered field is Archimedean.

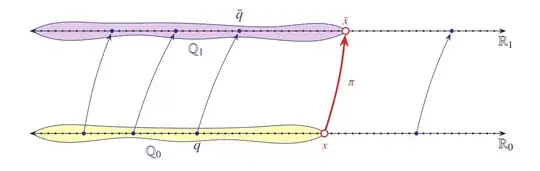

Suppose now that we have two complete ordered fields, $\R_0$ and $\R_1$. We form their respective prime subfields, that is, their copies of the rational numbers $\Q_0$ and $\Q_1$, by computing inside them all the finite quotients $\pm(1+1+\cdots+1)/(1+\cdots+1)$. This fractional representation itself provides an isomorphism of $\Q_0$ with $\Q_1$, indicated below with blue dots and arrows:

Next, by the Archimedean property, every number $x\in\R_0$ is determined by the cut it makes in $\Q_0$, indicated in yellow, and since $\R_1$ is complete, there is a counterpart $\bar x\in\R_1$ filling the corresponding cut in $\Q_1$, indicated in violet. Thus, we have defined a map $\pi:x\mapsto\bar x$ from $\R_0$ to $\R_1$. This map is surjective, since every $y\in\R_1$ determines a cut in $\Q_1$, and by the completeness of $\R_0$, there is an $x\in\R_0$ filling the corresponding cut. Finally, the map $\pi$ is a field isomorphism since it is the continuous extension to $\R_0$ of the isomorphism of $\Q_0$ with $\Q_1$. $\Box$

My expectation is that this theorem is familiar to almost every contemporary mathematician, and I furthermore find this theorem central to contemporary mathematical views on the philosophy of structuralism in mathematics. The view is that we are entitled to refer to the real numbers because we have a categorical characterization of them in the theorem. We needn't point to some canonical structure, like a canonical meter-bar held in some special case deep in Paris, but rather, we can describe the features that make the real numbers what they are: they are a complete ordered field.

Question. Who first proved or even stated this theorem?

It seems that Hilbert would be a natural candidate, and I would welcome evidence in favor of that. It seems however that Hilbert provided axioms for the real field that it was an Archimedean complete ordered field, which is strangely redundant, and it isn't clear to me whether he actually had the categoricity result.

Did Dedekind know it? Or someone else? Please provide evidence; it would be very welcome.