Sometimes (perhaps often?) vague or even outright incorrect arguments can sometimes be fruitful and eventually lead to important new ideas and correct arguments.

I'm looking for explicit examples of this phenomenon in mathematics.

Of course, most proof ideas start out vague and eventually crystallize. So I think the more incorrect/vague the original argument or idea, and the more important the final fruit, the better, as long as there is still a pretty direct connection from the vague idea to the final fruit.

Note: Many "paradoxes" sort-of are like this, but I think aren't what I'm looking for. (William Byers's book "How Mathematicians Think" has several examples and lots of discussion of the important role of paradox in mathematical research.) For example, the relationship between Russell's paradox, Godel's Incompleteness Theorem, and the undecidability of the halting problem (Church; Turing). But I think, unless the paradox has some other aspects of the vague-idea-as-fertilizer phenomenon, that I'm not looking for examples of paradoxes, though I am willing to be convinced otherwise.

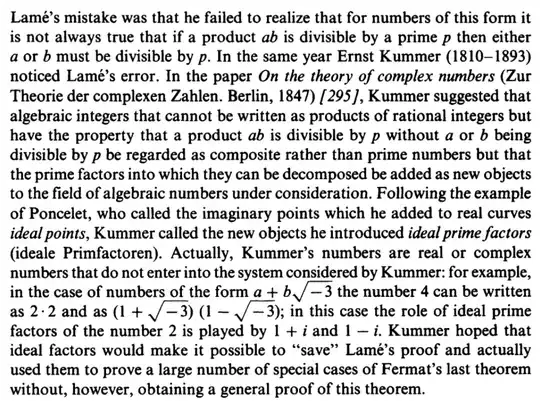

Edit: It's been suggested that this a duplicate of this other question, but I really think it is not. I am more interested in examples of outright incorrect (or nearly so) original statements that nonetheless lead to fruitful mathematics, whereas the other question seems to essentially be asking about ideas that start out intuitive, non-rigorous, or ill-defined and then are turned into rigorous arguments but along the same intuitive lines. (And, as I said above, I think I agree with one of the answers there that that is simply much of mathematics.) By comparing the answers to the other question to the three great answers already on this question (knot theory rising because Kelvin thought atoms were knotted strings; Lame's erroneous proof of FLT leading Kummer to develop algebraic integers; Lebesgue's incorrect proof that projections of Borel sets are Borel leading to Suslin's development of analytic sets), one can get a sense of the difference.