Here goes the elementary proof of the claim by Robert Houston that the quadraples $(P_1^{-1},P_2^{-1},P_3^{-1},P_4^{-1})$ and $(\cot \frac{\Omega_1}2,\cot \frac{\Omega_2}2,\cot \frac{\Omega_3}2,\cot \frac{\Omega_4}2)$ are affinely equivalent. In the spherical case the first quadraple should be replaced to $\{\cot\frac{P_i}2\}$, in the hyperbolic case to hyperbolic cotangents. Further the tetrahedron $A_1A_2A_3A_4$ is assumed to be generic (that implies the general case automatically.) I write the solution in Euclidean case, but the changes in spherical/hyperbolic case are almost straightforward, since the basic construction works in all three geometries.

At first, we note that if the quadraples $(a_1,a_2,a_3,a_4)$ and $(b_1,b_2,b_3,b_4)$ of reals satisfy $(a_1-a_2):(a_3-a_4)=(b_1-b_2):(b_3-b_4)$ and two other analogous relations, then they are affinely equivalent. Indeed, without loss of generality $a_4=b_4=0,a_3=b_3=1$, $a_1\leqslant a_2$ and we have $a_1-a_2=b_1-b_2$, $1+(a_1-a_2-1)/a_2=(a_1-1)/a_2=(b_1-1)/b_2=1+(b_1-b_2-1)/b_2$, $a_2=b_2$, $a_1=b_1$. So we have to prove (call it equation $(\star)$) that

$$

\frac{P_1^{-1}-P_3^{-1}}{\cot \frac{\Omega_1}2-\cot \frac{\Omega_3}2}=

\frac{P_3-P_1}{\sin \frac{\Omega_3-\Omega_1}2}\cdot\frac{\sin \frac{\Omega_1}2

\sin \frac{\Omega_3}2}{P_1P_3}

$$

equals to

$$

\frac{P_4-P_2}{\sin \frac{\Omega_4-\Omega_2}2}\cdot\frac{\sin \frac{\Omega_2}2

\sin \frac{\Omega_4}2}{P_2P_4}.

$$

In order to prove it we draw three planes: through $A_2$ orthogonal to the external bisector of $\angle A_1A_2A_3$, through $A_3$ orthogonal to the external bisector of $\angle A_2A_3A_4$, through $A_4$ orthogonal to the external bisector of $\angle A_3A_4A_1$.

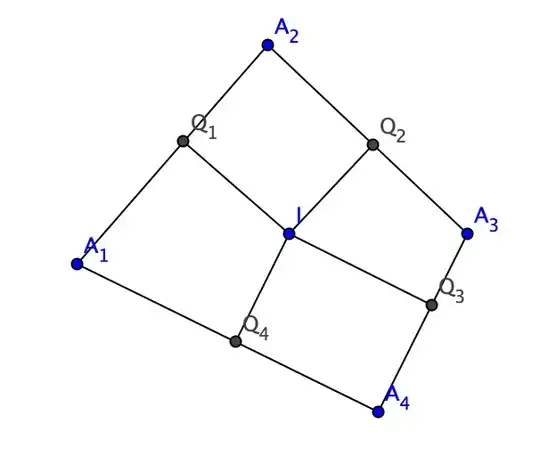

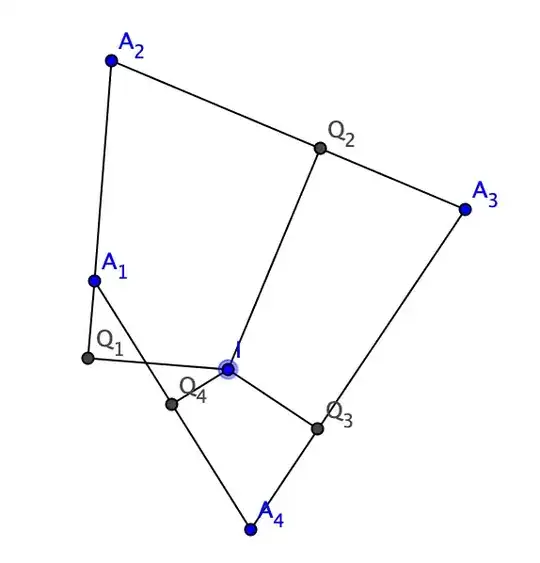

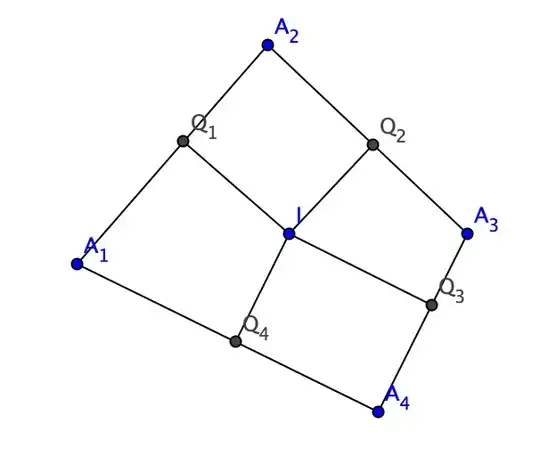

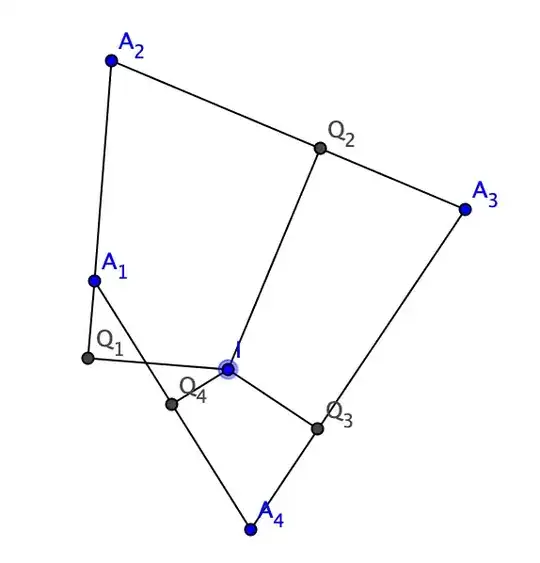

Let them meet at point $I$, and let $Q_1,Q_2,Q_3,Q_4$ be projections of $I$ onto lines $A_1A_2,A_2A_3,A_3A_4,A_4A_1$ respectively (see the picture). We have $IQ_1=IQ_2=IQ_3=IQ_4=:r$ and also $A_2Q_1=A_2Q_2$, $A_3Q_2=A_3Q_3$, $A_4Q_3=A_4Q_4$ by construction (the segments are directed in the natural sense: either $Q_1,Q_2$ both belong to rays $A_2A_1,A_2A_3$ respectively, or both do not, and so on). Also the right triangles $\triangle A_1IQ_1,\triangle A_1IQ_4$ are equal by hypotenuse and cathetus. Thus $A_1Q_1=A_1Q_4$. It implies that $$A_1A_2+A_3A_4=A_1Q_1+A_2Q_1+A_3Q_3+A_4Q_3=\\A_1Q_4+A_2Q_2+A_3Q_2+A_4Q_4=A_1A_4+A_2A_3,$$

which is not quite what you need but also an interesting relation. Well, to be serious, of course $Q_1Q_4$ is parallel to the internal, not external, bisector of $\angle A_2A_1A_4$:

Denoting $x_i=A_iQ_i$ we find (on this picture, in general we should consider directed segments) $x_2-x_1=l_{12},x_2+x_3=l_{23},x_3+x_4=l_{34},x_4+x_1=l_{14}$.

Thus $2x_{3}=l_{23}+l_{34}-l_{12}-l_{14}=P_1-P_3$, $2x_1=l_{14}+l_{23}-l_{12}-l_{34}$.

Analogously for dihedral angles we have four relations like $\angle(A_1A_2A_3,A_1A_2I)=\angle(A_1A_2A_3,A_2A_3I)=:\beta_4$,

$\angle(A_2A_3A_4,A_2A_3I)=\angle(A_2A_3A_4,A_3A_4I)=:\beta_1$,

$\angle(A_3A_4A_1,A_3A_4I)=\angle(A_3A_4A_1,A_4A_1I)=:\beta_2$,

$\angle(A_1A_2A_4,A_4A_1I)=\pi-\angle(A_1A_2A_4,A_1A_2I)=:\beta_3$

(suppose that $I$ lies inside the tetrahedron, otherwise carefully use directed angles: I am going to divide by 2 that is dangerous for the angels which are considered remainders modulo $\pi$, or consider several cases or use "generic case" abstract nonsense reasoning or whatever).

We get $\beta_4+\pi-\beta_3=\alpha_{12}$,$\beta_1+\beta_4=\alpha_{23}$,$\beta_2+\beta_1=\alpha_{34}$,$\beta_3+\beta_2=\alpha_{41}$; $2\beta_1=\alpha_{23}+\alpha_{34}+\pi-\alpha_{12}-\alpha_{41}=\pi+\Omega_3-\Omega_1$, $2\beta_3=\alpha_{23}+\alpha_{14}+\pi-\alpha_{12}-\alpha_{34}$.

Let $H$ be a projection of $I$ onto the plane $A_2A_3A_4$, then $A_3H$ is the internal

bisector of $\angle A_2A_3A_4$. We get $Q_2H=r\cos\beta_1=r\sin \frac{\Omega_1-\Omega_3}2$, $\frac{P_1-P_3}2=x_3=Q_2H\cot \frac{\angle A_2A_3A_4}2$. Therefore

$$

\frac{P_1-P_3}{2\sin \frac{\Omega_1-\Omega_3}2}=r\cot\frac{\angle A_2A_3A_4}2,

$$

analogously considering the vertex $A_1$ instead of $A_3$ we get

$$

\frac{l_{14}+l_{23}-l_{12}-l_{34}}{2\sin \frac{\alpha_{12}+\alpha_{34}-\alpha_{23}-\alpha_{14}}2}=r\tan \frac{\angle A_2A_1A_4}2.

$$

So we may exclude $r$ from the formulae and get

$$

\frac{P_1-P_3}{2\sin \frac{\Omega_1-\Omega_3}2}=

\frac{l_{14}+l_{23}-l_{12}-l_{34}}{2\sin \frac{\alpha_{12}+\alpha_{34}-\alpha_{23}-\alpha_{14}}2}\cdot \cot \frac{\angle A_2A_3A_4}2 \cot \frac{\angle A_2A_1A_4}2.

$$

Analogously

$$

\frac{P_2-P_4}{2\sin \frac{\Omega_2-\Omega_4}2}=

\frac{l_{14}+l_{23}-l_{12}-l_{34}}{2\sin \frac{\alpha_{12}+\alpha_{34}-\alpha_{23}-\alpha_{14}}2}\cdot \cot \frac{\angle A_1A_2A_3}2 \cot \frac{\angle A_1A_4A_3}2.

$$

Therefore $(\star)$ reads as

$$

\frac{\sin \frac{\Omega_1} 2\sin \frac{\Omega_3} 2}{P_1P_3}\cot \frac{\angle A_2A_3A_4}2 \cot \frac{\angle A_2A_1A_4}2=

\frac{\sin \frac{\Omega_2} 2\sin \frac{\Omega_4} 2}{P_2P_4}\cot \frac{\angle A_1A_2A_3}2 \cot \frac{\angle A_1A_4A_3}2.

$$

This immediately follows from the following "sine theorem" for the tetrahedron: the expression

$$

\frac{\sin \frac{\Omega_1} 2

\sqrt{\cot \frac{\angle A_2A_1A_3}2 \cot \frac{\angle A_2A_1A_4}2\cot \frac{\angle A_3A_1A_4}2}

}

{P_1\sqrt{\tan \frac{\angle A_2A_3A_4}2 \tan \frac{\angle A_2A_4A_3}2 \tan \frac{\angle A_3A_2A_4}2}}

$$

(denote it $\eta_1$) equals to analogous expressions for other indices.

For proving it we denote $S_1$ and $r_1=2S_1/P_1$ the area and inradius of $\triangle A_2A_3A_4$, then we have

$$

P_1^2\tan \frac{\angle A_2A_3A_4}2\tan \frac{\angle A_3A_2A_4}2

\tan \frac{\angle A_2A_4A_3}2=P_1^2\cdot\frac{r_1^3}{(P_1/2-l_{24})

(P_1/2-l_{34})(P_1/2-l_{23})}=\\

\frac{(2S_1)^3}{4(P_1/2)(P_1/2-l_{24})

(P_1/2-l_{34})(P_1/2-l_{23})}=\frac{8S_1^3}{4S_1^2}=2S_1

$$

by Heron formula. Next, using the Cagnoli formula (see p. 101 here)

$$\sin \frac{\Omega_1}2=\sin \alpha_{12}\frac{\sin \frac{\angle A_3A_1A_2}2\sin \frac{\angle A_4A_1A_2}2}{\cos \frac{\angle A_3A_1A_4}2}$$

we get

$$\sin^2 \frac{\Omega_1}2

\cot \frac{\angle A_2A_1A_4}2\cot \frac{\angle A_2A_1A_3}2\cot \frac{\angle A_3A_1A_4}2

=\sin^2 \alpha_{12}\frac{\sin \angle A_3A_1A_2\sin \angle A_4A_1A_2}{2\sin \angle A_3A_1A_4}.$$

So, $\eta_1^2=\eta_2^2$ reads as

$$

\frac{\sin \angle A_3A_1A_2\sin \angle A_4A_1A_2}{S_1\cdot \sin \angle A_3A_1A_4}=

\frac{\sin \angle A_3A_2A_1\sin \angle A_4A_2A_1}{S_2\cdot \sin \angle A_3A_2A_4}.

$$

Substituting $2S_2=l_{13}\cdot l_{14}\cdot \sin \angle A_3A_1A_4$,

$2S_1=l_{23}\cdot l_{24}\cdot \sin \angle A_3A_2A_4$ this reduces to a product of two sine laws, and everything is proved.

Note that we had the expression $l_{12}-l_{23}+l_{34}-l_{41}$ above, and if you replace the internal bisectors to external bisectors you may also get $l_{12}+l_{23}+l_{34}+l_{41}$ that should answer to your extended question.