(This is a joint musing with Andrew Gordon and Wyatt Mackey)

There is a classic, elementary riddle, discussed before on MO and math.SE: suppose you have 1000 bottles of wine, and one is poisoned. The poison is slow-acting, and will not cause any negative effects until 24 hours after consumed. How many taste-testers (for the sake of humanity, let's say they are rats) do you need to determine which bottle is poisoned by the end of the 24 hours? There is a natural generalization to this problem, which is discussed here: what if there are two poisoned bottles? What about three?

The accepted answer of Sergey Norin cites a paper of Frankl and Furedi that develops theory to give a constructible solution of 43 taste-testers for the case of 1000 bottles, 2 of which are poisoned.

Apparently, there are also some sources out there that give the exact lower bound at 19 testers.

Our version of the problem extends the original one in a different direction: suppose there is one poisoned bottle and one bottle with antidote, so that any taste-tester who consumes wine from both the poison and antidote bottles will show no adverse effects. Then what is the fewest number of testers needed to locate the poisoned bottle?

This question as well has two further related questions:

Assume that the antidote, when consumed without the poison, is also poisonous (this is not so ridiculous a situation: according to this article, the chemical atropine, while poisonous when consumed on its own, counteracts anthrax)

Locate the antidote in addition to the poison.

We have had quite a bit of fun coming up with various solutions to this problem, but have been unable to determine an optimal one. For completeness and (perhaps) amusement, I'll present two of ours here:

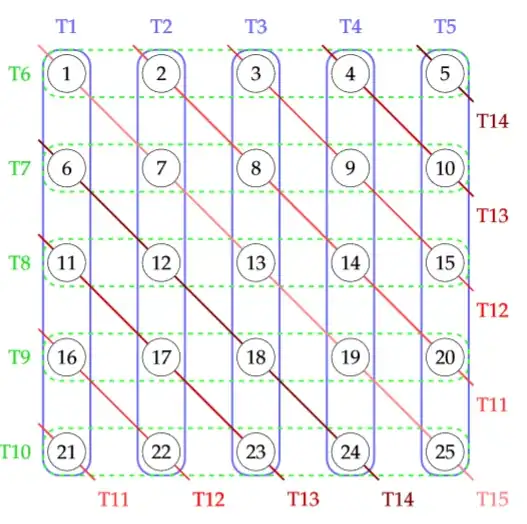

First, we can find the poisoned bottle in a cellar of $n$ wines with $3\lceil\sqrt{n}\rceil - 1$ testers. The $-1$ is because we can leave out one bottle from the testing and still find all the information we need: if that bottle is poisoned, no one dies. If it isn't poisoned, we will have already found the poisoned one. We'll divvy up the tasting responsibilities as follows: arrange the bottles in a square (hence the $\lceil \sqrt{n}\rceil$); assign one taste-tester to all the bottles in each row, one to all the bottles in each column, and one to all the bottles along a diagonal, where the diagonals "wrap around":

Another construction is significantly less efficient and pointless, but sort of fun. If we consider testers as points in a finite projective space $\mathbb{P}_q^n : = \mathbb{P}\mathbb{F}_q^n$ for $q = p^e$ a prime power, and bottles of wine as lines in such a projective space, then a tester will drink from a bottle if and only if the corresponding point lies on the corresponding line. The problem can thus be transformed to the following, which would give an upper bound:

Question 1 Fix an integer $n$. For what prime power $q$ and what dimension $m$ does $\mathbb{P}_q^m$ contain at least $n$ lines and have the minimum number of points?

Perhaps "the problem can be reduced to" was not a great choice of words; I mean, any solution to Question 1 would give an upper bound to our problem, because lines in finite projective spaces contain at least three points, and those data are enough to distinguish any two points. The numbers of points and lines in finite projective spaces are known, so you can write a quick script to check for a minimum within some reasonable range of prime powers.

Anyway, our ideas were clearly insufficient, because Noam Elkies knocked them out of the park overnight (literally), the following two algorithms being due to him:

Solution #1: We can solve this with $O(\log_2(n)^2)$ testers as follows. The solution to the 1-poison, no antidote problem comes from assigning a tester to each bit when the bottles are numbered base-2; this solution comes from assigning four testers to each pair of bits. That is, each pair of bits can be 00, 01, 10, or 11, and we assign a tester to each of those possibilities. This requires $2\ell(\ell - 1)$ testers, where $\ell = \lceil \log_2(n) \rceil$.

Solution #2: This one is $O(\log_2(n))$, the best we could possibly get via information-theoretic considerations, and it is non-constructive. So that I don't risk botching the construction, I'll quote directly Noam's solution:

Choose $k$ subsets of the $n$ bottles at random. (It will make the calculation easier if they're chosen independently "with replacement" so there's a positive albeit small possibly of stupidly choosing the same set twice.) Once $k \gg \log(n)$, the probability that such a random choice works should be positive, so in particular some choice must work.

A collection of subsets fails if there's some two (poison, antidote) pairs $(x,y)$ and $(x',y')$ that they can't distinguish; that is, such that for each set $S$ the events ($S$ contains $x$ but not $y$) and ($S$ contains $x'$ but not $y'$) either both happen or both don't happen. We want to show that once $k \gg \log(n)$ the expected number of such pairs of pairs is less than 1, which makes the success probability positive. Well, the expected number is just the sum over $\{(x,y), (x',y')\}$ of the probability that none of our sets distinguishes between them; and that probability is the $k$-th power of the probability that one set does not distinguish them. This one-set probability depends on which if any of the four coincidences $x=x', y=y', x=y', x'=y$ occur, but that's a finite number of possibilities, and for each of them we should get some probability $c<1$. So we can just take the largest of these and multiply its $k$-th power by the number of $\{(x,y), (x',y')\}$, which is less than $n^4$. Once $k$ exceeds some multiple of $\log(n)$, the resulting expected number $c^k n^4$ of failures falls below 1 and we're done.

Further refinements would include a more precise accounting of how many times each subset of the four coincidences occurs (e.g. there are only $O(n^3)$ ways to have $x=x'$; the full $n^4$ happens only when $x,x',y,y'$ are all distinct), or choosing randomly not among all subsets but only from subsets of size $\sim f \cdot n$ for some fixed $f$ in $(0,1)$ which would then be optimized by some possibly annoying calculus exercise.

For the generalization to $p$ poison bottles we should likewise get $O_p(\log(n))$: there are $n^{2p}$ possible failures, so $k$ must be large enough to make $c^k n^{2p} < 1$, but that's still a constant multiple of $\log(n)$.

This asymptotic improvement is fantastic, but we still don't know the answer in any specific cases. Might anyone have leads?