I did some numerical experiments about $\{ \frac{a}{b}: a,b \in A, \;a < \, b\}$ for various integer sets $A$. Does anyone recognize these densities?

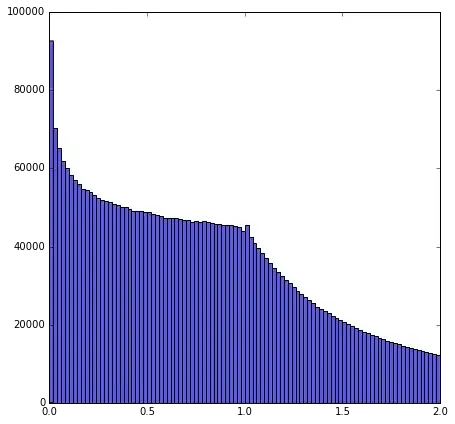

Here is $A = \{ p: \text{prime}\}$

Here is $A = \mathbb{Z}$

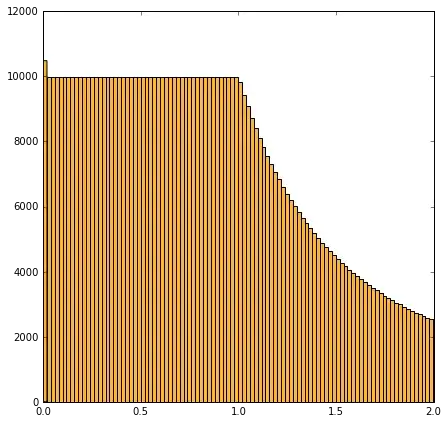

Here is if $\{ (a,b): a < 2 \, b, \; \gcd(a,b) = 1 \}$. Does this uniform distribution surprise everybody?

Literature on each of these could be interesting. I know there is discussion about the primes case being dense already:

By default I can look for the Weyl Equidistribution Theorem. We are told to evaluate sums:

$$ c_N(m) = \sum_{0 < a < b < N} e^{2\pi i m \frac{a}{b}} $$

These are the sums of Ramanujan, $c_q(n)$. This paper of Huxley states in the affirmative, and - in usual style - the result is so obvious he does not prove it.

In another place Huxley works it out. He shows (unconditionally) just reasoning about fractions:

$$ \sum_{n=1}^N e^{ 2\pi i \, m \frac{a}{b}} \ll d(m) \sqrt{N} $$ and this is Weyl's criterion. The other lemma I like is: Let $0 < x_n < 1$ be the Farey fractions between $0$ and $1$:

$$ \sum_{n=1}^N e(m x_n) = \sum_{d|m} d \left[ M( \tfrac{Q}{d}) \right] $$

where $M(x) = \sum_{m \leq x} \mu(m)$. No effort was taken to optimize exponent. This is already equivalent to $M(x) = o(x)$.

This is taken from Chapter 1 Huxley's book Area, Lattice Points, and Exponential Sums