Having solved the eigenvalue problem $$y''+ λ y=0, 0 \leq x \leq L$$ $$y(0)=y(L)=0$$ which solution is: $$\text{The eigenvalues are: } λ_n=(\frac{n \pi}{L})^2$$ $$\text{ and the eigenfuctions are: }y_n=\sin (\frac{n \pi x}{L})$$

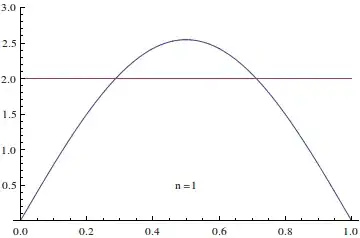

I am asked to expand the function $f(x)=2$ to the eigenfunctions of the problem.

At an other exercise in my notes there is the following: $$\text{Since the problem is Sturm-Liouville, each function } f(x), 0 \leq x \leq L \text{ with } f(0)=f(L)=0, \text{ can be written as a sum of the eigenfunctions, so}$$ $$f(x)=\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}{c_n \sin(\frac{n \pi x}{L})}$$

But in this case $f(x)=2$ and it does not stand that $f(0)=f(L)=0$. What can I do? Can I use the sentence above though?