Caveat: The following is only a partial solution. Some parts are proven or mostly proven, but others are just conjectures. I hope it helps, and I also hope this question gets more answers to get the rest of the way there.

I'm going to use $P$ for perimeter and $A$ for area. Let $S$ be the convex shape we create, and $\partial S$ be the boundary of $S$.

Lower bound for $\mathbf{P}$

This is quite related to the isoperimetric problem, where we'd normally think about maximixing area while keeping perimeter fixed, but it comes out pretty much the same.

Small $A$

For $A \le \frac \pi 4$, the usual isoperimetric inequality directly shows that the smallest $P$ will be achieved when $\partial S$ is a circle with radius $r = \sqrt{A/\pi}$. The corresponding $P$ will be $2 \sqrt{A\pi}$.

Big $A$

For larger $A$, here is a link to Gilbert Strang's paper "Maximum Area with Minkowski Measures of Perimeter". Section 5 is relevant; it directly concludes that the maximum perimeter-to-area ratio for shapes inside the square is $\frac P A = 2 + \pi$, with $\partial S$ made of four circular arcs near the corners, connected by segments that lie on top of the boundary of the square. He includes a diagram; note that the corners are meant to be circular arcs and their jagged look is just a failure of the author's diagramming skills.

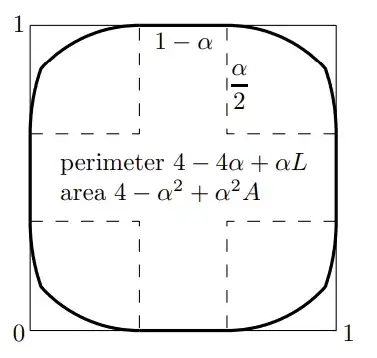

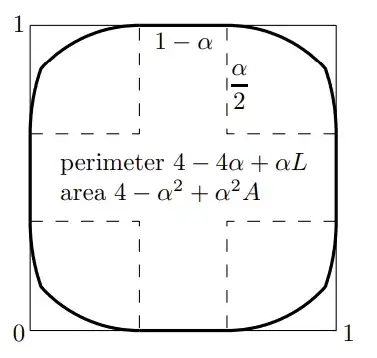

That doesn't directly address your problem, except for providing the minimal $P$ for the specific case where $A = $ the area of that shape. However, I think the paper's methods also show that for $A > \frac \pi 4$, the minimal $P$ will always be achieved by some shape of that form. In other words, we should use four line segments along the sides, and four circular arcs near the corners, and the radius of those circular arcs is determined by the specific $A$ we've chosen. Using that construction, I get the lower bound $$P^{lo} = 4 - 2 \sqrt{(1-A)(4-\pi)}.$$

Here is my attempt to bullet-point the paper's argument supporting this optimality claim:

- $\partial S$ should touch the boundary of the square. (Roughly, this is true because if we ignored the "stay inside the square" condition then the optimal answer would be a circle that goes outside the square.)

- At the points where $\partial S$ separates from the boundary of the square, $\partial S$ should be tangent to the boundary of the square. (I don't have a good explanation here...)

- The parts of $\partial S$ in the interior of the square should be part of a valid "isoperimetrix" - in our case, part of a circle. (The idea is that we're away from the boundary, so the constraint about staying inside the square is "not active" here.)

Upper bound for $\mathbf{P}$

Trivial observation: we can always achieve $P \ge 2 \sqrt 2$ even if $A$ is tiny, since we could use the diagonal of the square with some tiny width.

Here are a few shapes we could think about:

- For $A \le \frac 1 2$, use a triangle with vertices $(0,0)$, $(2A-1,0)$, and $(1,1)$. For $A > \frac 1 2$, do the same thing in the other half of the square by using a quadrilateral with vertices $(0,0)$, $(1,0)$, $(1,1)$, $(0,2A)$. This method gives a perimeter of $P^{hi}_1(A) = \sqrt 2 + 2A + \sqrt{1 + (1-2A)^2}$ for $A \le \frac 1 2$ and $P^{hi}_1(A) = 2 + (2A-1) + \sqrt{1 + (2-2A)^2}$ for $A > \frac 1 2$.

- Instead of expanding into the upper and lower triangles one at a time, we could consider expanding equally in both directions. In other words, we could use a quadrilateral with vertices $(0,0)$, $(A,0)$, $(1,1)$, $(0,A)$. This gives perimeter of $P^{hi}_2(A) = 2A + 2 \sqrt{A^2-2A+2}$. Unfortunately, this perimeter is worse (smaller) than $P^{hi}_1$. This is easy to check using graphing tools; alternatively, it's essentially true because $\frac{ \partial^2 P^{hi}_1}{(\partial A)^2} \ge 0$ for $0 \le A \le \frac 1 2$.

- We could also try using rhombi or triangles where the extra vertices are on the line $y = 1-x$. In other words, we could consider a rhombus with vertices $(0,0), (\frac 1 2 + c, \frac 1 2 - c), (1,1), (\frac 1 2 - c, \frac 1 2 + c)$ where $c$ is chosen to get the correct area. This is the same as the "rhombus whose long diagonal is a diagonal of the square" suggested by a commenter above. I get the same final perimeter as they did: $P^{hi}_3 = 2 \sqrt{2 + 2A^2}$. Unfortunately, this is once again worse than option (1).

Overall, option (1) is my own best attempt, and it's my low-confidence conjecture for the optimal shape. I don't have a proof though. Interested to see whether someone does better (or proves my conjecture) in another answer.

Everything in between the lower and upper bounds

I agree with the commenter Sarvesh who states that the set of possible perimeters should be an interval. The proof could roughly involve "continuously mutating the smallest-perimeter $S$ into the largest-perimeter $S$ while keeping $A$ constant". I am certainly not claiming you should be fully convinced by this very handwavy statement though.