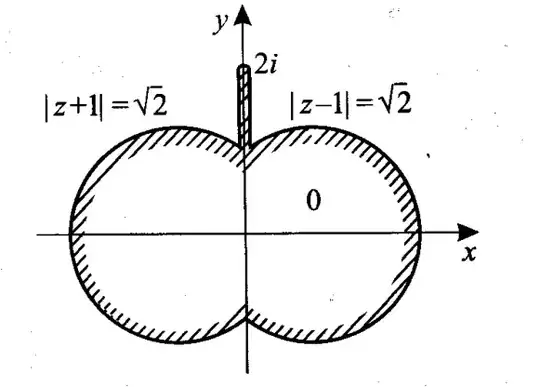

First step: I see two circles that intersect at two points, so I automatically want to simplify them using a Mobius transformation $T$ that maps those two intersection points $i$ and $-i$ to $T(i) = 0$ and $T(-i) = \infty$. Lines through 0 are just way easier to handle than random circles.

We have an extra degree of freedom available (see Wikipedia; we're allowed to choose any 3 points and specify their destinations) so we might as well also map $2i \mapsto 1$.

The Mobius transformation accomplishing all of this is $T(z) = 3\frac{z-i}{z+i}$. The resulting domain is $$T(D) = \left \{ r e^{i \theta} : r > 0, -\frac{\pi}{4} < \theta < \frac{\pi}{4} \right \} \setminus (0, 1]$$

For the next step, the idea is that we should map the domain to "$\mathbb{C}$ minus a ray that starts at 0". Applying the $z \mapsto z^4$ would map our current domain to $\mathbb{C} \setminus (-\infty, 1]$, so we should instead use $f(z) = z^4 - 1$ so that $f(T(D)) = \mathbb{C} \setminus (-\infty, 0]$.

At this point I'm guessing you're in more familiar territory. We can now apply $g(z) = \sqrt{z}$ to map our domain to $g(f(T(D))) = \{z \in \mathbb{C} : Re(z) > 0\}$. Finally, you wanted the upper half plane instead of the right half plane, so we should apply $h(z) = iz$ to make the necessary rotation.

The final conformal mapping $\alpha : D \to \{z \in \mathbb{C} : Im(z) > 0\}$ is the composition of all these steps: $\alpha(z) = h(g(f(T(z))))$.

One followup question you might have is - How did I know what the domain $T(D)$ looks like? My answer is that I again used the idea "you can find where a Mobius transformation sent a circle if you check the destinations of 3 points on that circle". For example, for the circle $|z-1|=\sqrt{2}$, I already knew $T(i) = 0$ and $T(-i) = \infty$. To get a third point, I plugged in to find $T(1+\sqrt{2}) = 3 e^{-\frac{i\pi}{4}}$. That's enough to prove that the circle $|z-1|=\sqrt{2}$ gets mapped by $T$ to the line through $0$ and $e^{-\frac{i \pi}{4}}$. Similarly, I found $T$ maps the circle $|z-1|=-\sqrt{2}$ to the line through $0$ and $e^{\frac{i \pi}{4}}$. Those lines divide $\mathbb{C}$ into four regions, so $D$ must have gotten mapped to one of those regions. To find out which one, I can just plug in one more point that's in $D$. For example, $T(3i) = 3/2$, so that means the correct region will be the one with $\arg(z) \in (-\frac \pi 4, \frac \pi 4)$. (After that we still need to figure out what $T$ does to the slit, but that's more straightforward.)