Proposition. For any natural number $p$ we have $I_{p,\infty}=0$.

Proof. As $I_{p,q}$ is even we have $$I_{p,q}=\frac14\int_{-\pi}^\pi\int_{-\pi}^\pi\frac{\sin x\sin px\cos qy}{\sin^2x+\sin^2y}\,dx\,dy\tag1.$$ Define $a:=\sin^2y$. Let $w=e^{ix}$ and $C=\{w:|w|=1\}$ so that \begin{align}\int_{-\pi}^\pi\frac{\sin x\sin px}{\sin^2x+\sin^2y}\,dx&=\oint_C\frac{\frac{w-1/w}{2i}\cdot\frac{w^p-1/w^p}{2i}}{\frac{(w-1/w)^2}{-4}+a}\frac{dw}{iw}=-i\oint_C\frac{(w^2-1)(w^{2p}-1)}{w^p(w^4-(4a+2)w^2+1)}\,dw.\end{align} Inside $C$ there is a pole at $w_0=0$ of order $p$ and simple poles at $w_{1,2}=\pm\sqrt{2a+1-2\sqrt{a^2+a}}$. Letting $f(w)$ be the integrand and $t=w_{1,2}^2$, we obtain \begin{align}\int_{-\pi}^\pi\frac{\sin x\sin px}{\sin^2x+\sin^2y}\,dx&=2\pi(\operatorname{Res}(f,0)+2\operatorname{Res}(f,\sqrt t))\end{align} where $\operatorname{Res}(f,\sqrt t)=(t-1)(t^p-1)t^{-p/2}(a^2+a)^{-1/2}/4$. To evaluate the residue at $0$, note that \begin{align}(p-1)!\operatorname{Res}(f,0)=\lim_{w\to0}\frac{d^{p-1}}{dw^{p-1}}\frac{(w^2-1)(w^{2p}-1)}{w^4-(4a+2)w^2+1}=\lim_{w\to0}\frac{d^{p-1}}{dw^{p-1}}\frac{-w^2+1}{w^4-(4a+2)w^2+1}\end{align} after clearing terms of orders higher than $p-1$. Define $h(w):=(w^4-2(2a+1)w^2+1)^{-1}$ and invoking Leibniz's rule yields $$(p-1)!\operatorname{Res}(f,0)=h^{(p-1)}(0)-2\binom{p-1}2h^{(p-3)}(0)\implies\operatorname{Res}(f,0)=\frac{h^{(p-1)}(0)}{(p-1)!}-\frac{h^{(p-3)}(0)}{(p-3)!}$$ Substituting this into $(1)$ gives \begin{align}I_{p,q}&=2\pi\Re\int_0^{\pi/2}\left(\operatorname{Res}(f,0)+2\operatorname{Res}(f,\sqrt t)\right)e^{iqy}\,dy\end{align} and it follows from the Riemann-Lebesgue lemma that $I_{p,\infty}=0$ provided that the sum of the residues is $L^1$-integrable. It is evident that $|\operatorname{Res}(f,0)|<\infty$ as it is a polynomial in $2\sin^2y+1$, since for all derivatives, the denominator at zero is $1$. Finally, as $t(a)$ is decreasing and non-negative, $$\operatorname{Res}(f,\sqrt t)<\frac{(t-1)(t^p-1)}{\sqrt{a^2+a}}t(a=1)^{-p/2}=2t(a=1)^{-p/2}\left(\frac a{a^2+a}-1\right)(t^p-1)<\infty$$ so the criterion is met.

Repeating the process above for $q$, we have $$\int_{-\pi}^\pi\frac{\cos qy}{\sin^2x+\sin^2y}\,dy=2i\oint_D\frac{z^{2q}+1}{z^{q-1}(z^4-(4b+2)z^2+1)}\,dz$$ where $D$ is the unit disk defined by $z=e^{iy}$ and $b:=\sin^2x$. Notice the denominator of the integrand $g(z)$ is essentially the same as that of $f(w)$ so the computations will be very similar. Hence $$I_{p,q}=-2\pi\Im\int_0^\pi\sin x\cdot(\operatorname{Res}(g,0)+2\operatorname{Res}(g,z^*))e^{ipx}\,dx$$ where $z^*=\sqrt{2b+1-2\sqrt{b^2+b}}$ and the same conclusion should follow.

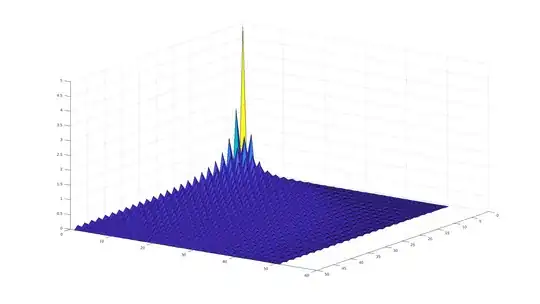

$I_{p,q}$ as a function of $p$ and $q$" />

$I_{p,q}$ as a function of $p$ and $q$" />