(1 + 1/n)^n approximates e^1.

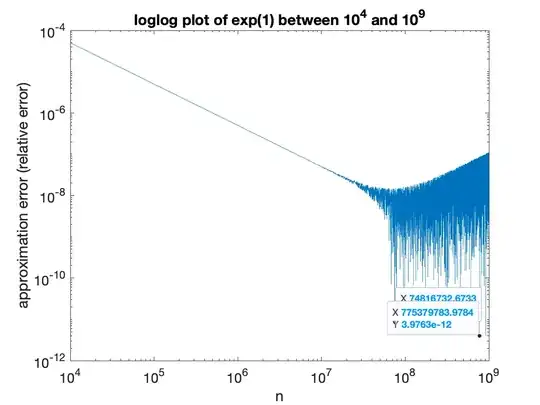

Case 1: When n is equally spaced between 10^4 and 10^9 with 10000 different numbers, linspace(10.^4, 10.^9, 10000) (Done in Matlab). Here's the graph:

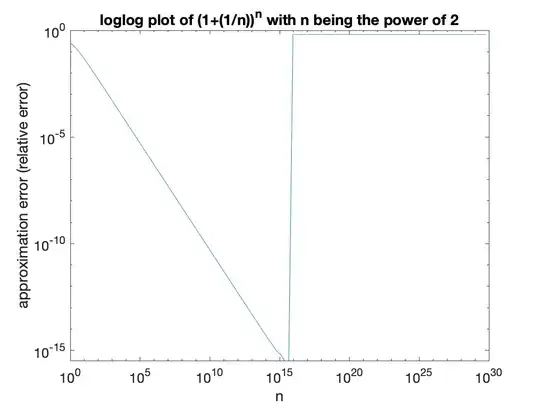

Case 2: When n is in power of 2, i.e. 2^0, 2^1, 2^2..... Here's the graph:

I just started to learn numerical analysis, so this really puzzles me.

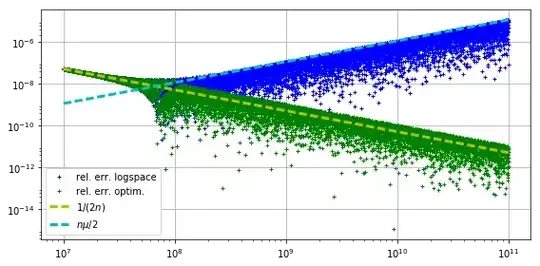

I am wondering what's the logic behind it. I understand that 1 + 1/n can't be represented correctly in floating point number, so when calculating there would be error like this: 1 + 1/n + δ. But why is that the 2 graphs are so different though? Case 1, the graph fluctuates drastically between 10^8 to 10^9. But in case 2, from 10^8 to 10^9, it's a straight line. And starting from 10^15, the round-off errors are exponentially increasing..... why?

I should note that the calculation is done in 16 digits of precision. In 32 digits of precision, both cases produce straight line. But I would like to know why is that in 16 digits of precision, things are so different.

2.220446049250313e-16. That is why for $n$ somewhat larger than $10^6$ the $1+1/n$ becomes just $1$. – logarithm May 24 '19 at 23:01