The Gaussian curvature value $G$ is the product of the two principal curvatures, which are the largest, $\kappa_1$, and the smallest (most downwards-curving), $\kappa_2$, normal curvatures through a point): $$G=\kappa_1\kappa_2$$

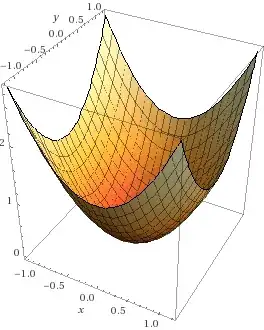

For a mountain top as well as a valley, we have a positive $G>0$, because both principle curvatures are either upwards or downwards. The same is the case for a sphere (rightmost figure below). A saddle point, on the other hand, will have negative $G<0$ (leftmost figure). And a flat surface as well as a surface which is 'flat' in one dimension, such as a cylinder (middle figure), will have $G=0$.

Image from Wikipedia

Image from Wikipedia

My question is regarding a specific claim from the article on Gaussian curvatures on Wikipedia ("Relation to geometries" headline, middle sentence):

When a surface has a constant zero Gaussian curvature, then it is a developable surface and the geometry of the surface is Euclidean geometry.

When a surface has a constant positive Gaussian curvature, then it is a sphere and the geometry of the surface is spherical geometry.

When a surface has a constant negative Gaussian curvature, then it is a pseudospherical surface and the geometry of the surface is hyperbolic geometry.

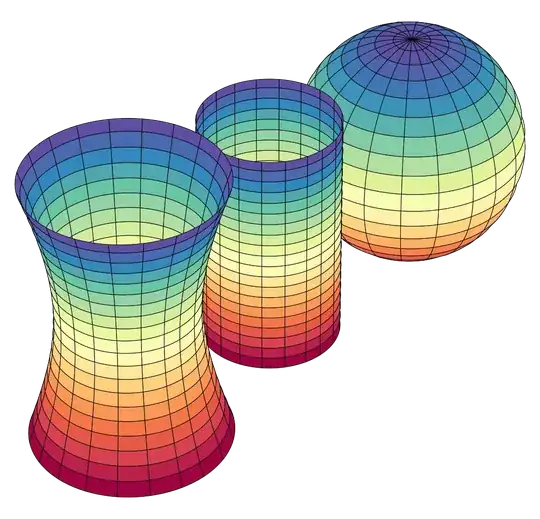

These three sentences seemingly cover all types of surfaces. But the middle sentence (I have emphasized it) tells that for a positive $G>0$, the curvature is a sphere. How can that be true? Don't many mountain top surfaces have a positive $G>0$ all the way down from the top to forever? Such as the function $f=x^2+y^2$ (graph below)?

from WolframAlpha