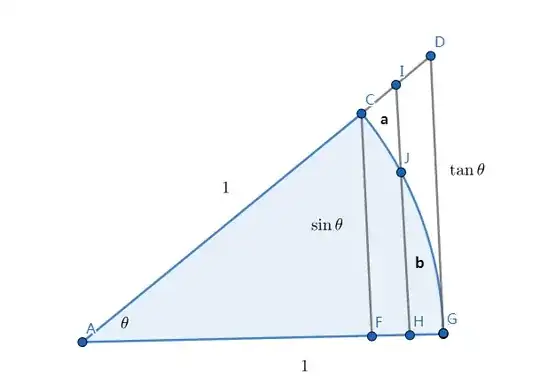

I could show in calculus where $0<θ<\frac{\pi}{2}$ like this

$$\frac{d(θ)}{dθ}=1<\frac{1}{2}(\cosθ+\sec^2θ)$$

But I curioused about would it could prove by geometric way likewise trigonometric identities. I try to show with the area of circular sector but I failed...

So this is question:

How to show $$\frac{\sinθ +\tanθ}{2}>\theta$$ where $0<\theta<\frac{\pi}{2}$ in geometric way?