The problem of showing the equivalence between the Cauchy (definite) integral defined below and the Riemann integral is an exercise with hint in C.R.Rosentrater, Varieties of Integration, 2015.

I am interested in one direction, precisely the one contained in exercise 32 of chapter 3. Its converse, easy to prove, is contained in exercise 38 chapter 2.

In what follows $\mathcal P_L$ indicates the partition $\mathcal P$ tagged by the left endpoints of its subintervals.

The symbol $S_R$ indicates a Riemann sum.

A Cauchy sum is a Riemann sum referred to a partition tagged by the left endpoints.

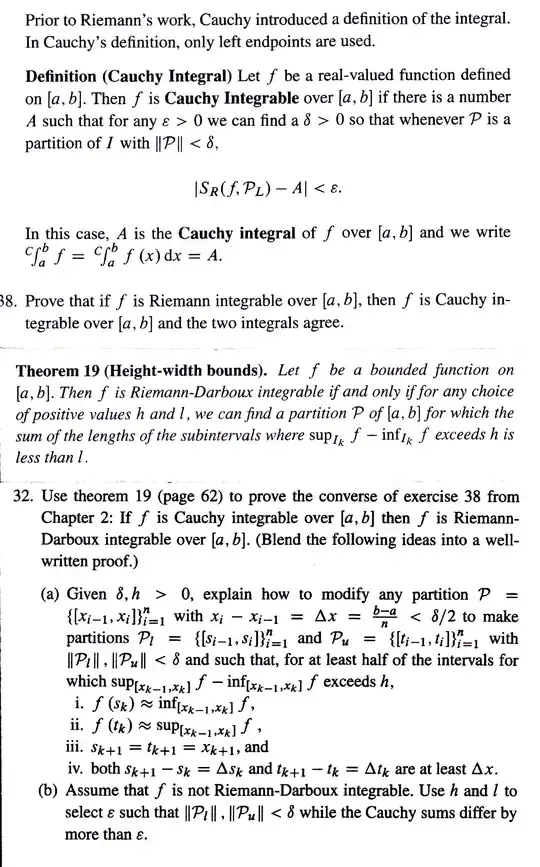

It is clear that $f$ is Cauchy integrable over $[a,b]\,$ only if,$\,$ for any $\varepsilon>0$, we can find a $\delta>0$ so that, whenever $\mathcal P$ and $\mathcal Q$ are partitions of $[a,b]$ with $\|\mathcal P\|<\delta$ and $\|\mathcal Q\|<\delta$, one has $$|S_R(f,\mathcal P_L)-S_R(f,\mathcal Q_L)|<\varepsilon$$ Author suggests a proof by contraposition using a characterization of Riemann integrability, called there "height-width bounds theorem".

The statement to be proved is

If $f$ is bounded and Cauchy integrable over $[a,b]$, then $f$ is Riemann integrable over $[a,b]$

I restated what is written in exercise 32 because Cauchy integrability doesn't imply boundedness.

This problem appears here and there in the literature but, as far as I know, proofs are not at all elementary. Maybe Rosentrater's hint refers to an elementary one.

I don't know how to use the hint. I am waiting for a further hint at least.

Many thanks in advance.