Given that $2^n - 3^m > 0$, I know that $n > m\log_{2}3$ (*). If $2^n - 3^m \geqslant 2^{n-m}-1$, $n>= m + \log_{2}\frac{3^m-1}{2^m-1}$ (**).

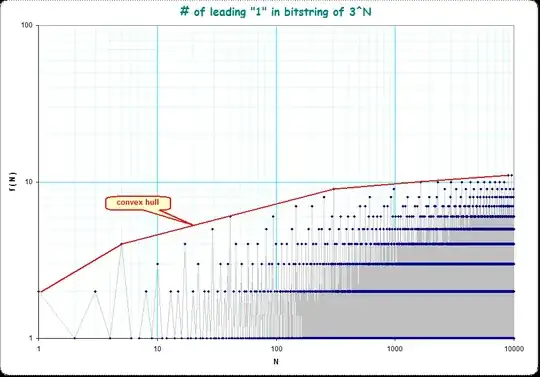

This is the result when I graph it out ($m$ -> $x$, $n$ -> $y$): https://i.stack.imgur.com/yRCu7.png (*) and (**) correspond to the red and blue shaded area, respectively. The inequality could be stated that for $m$, $n$ integers, if $(m, n)$ lies in the red area, it's also in the blue area. In other words, there's no in lattice point in the only-red-shaded area.

The mentioned critical region is bounded by the y-axis (given that $m$, $n$ are positive), the straight line $y_1 = x \log_{2}3$, and the curve $y_2 = x + \log_{2}\frac{3^x-1}{2^x-1}$ that approaches $y_1$ as $x$ approaches infinity (proven using limits). Since $\log_{2}3$ is irrational, $y_1$ does not pass through any lattice point (except at origin), and the distance between $y_2$ and $y_1$ gets smaller and smaller as $x$ gets larger, it is more and more unlikely that the critical region passes through some lattice points when $x$ increases. This support my observation that for large m (say $m=100$), $2^n-3^m$ is not just "larger than or equal" to $2^{n-m}-1$ but EXTREMELY larger ($3\cdot 10^{29}$ times larger in this case)! The gap between the two tends to get bigger as m increases, which makes me believe the inequality is true for all numbers.

For another approach, I see that the inequality has more chance to fail as $n$ decreases and/or $m$ increases; in other words, we just need to take $n$ as a function $n(m)$ equals to the smallest possible number such that $n > m\log_{2}3$. Since $n$ is integer, $n(m) = \lceil m\log_{2}3\rceil$.

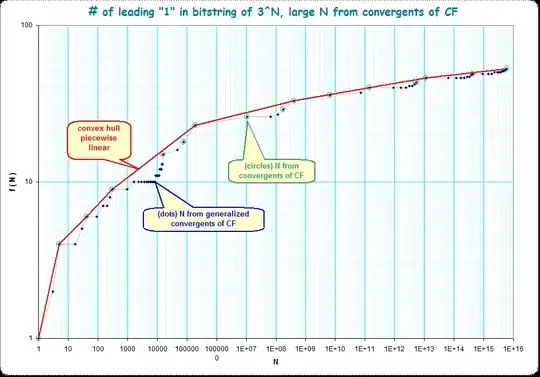

Now replace $n$ with $n(m)$ in (**): $$\lceil m\log_{2}3\rceil \geqslant m + \log_{2}\frac{3^m-1}{2^m-1}.$$ Subtract both sides by $\log_{2}(3)m$: $$\lceil m\log_{2}3\rceil - m\log_{2}3 \geqslant \log_{2}\frac{3^m-1}{2^m-1} - m\log_{2}\left(\frac{3}{2}\right).$$ The left side of the inequality is the difference of $m\log_{2}3$ and its rounded-up integer, the right side is the difference of $y_2$ and $y_1$ in the graphing section. Here is the graph of the two: https://i.stack.imgur.com/sxwjY.png Blue and red line correspond to left and right side, respectively; horizontal axis represents $m$. As seen, the left side values jumps back and forth somewhere between $0$ and $1$, while the right approaches zero very quickly (already $0.000175$ at $m=13$), so I hypothesized that the inequality is always true, which would prove the conjecture in my question. However, I have no idea where to go next, since the value of $\lceil m\log_{2}3\rceil - m\log_{2}3$ looks pretty "random" to me; I mean, $m\log_{2}(3)$ is an irrational number (has infinitely many decimal values with no pattern), how can I predict the difference of its rounded-up integer and itself?

By the way, I noticed this inequality while trying to solve the Collatz conjecture, and I'm just curious whether it's really true for all numbers or not (I have checked it with computer for m up to 10 billion). My approach above might be completely wrong, so don't just stick with it. I appreciate any thoughts/suggestions of yours about this conjecture or directions I should go that may help proving this.

Thanks a lot.