$\require{begingroup} \begingroup

\newcommand{idiv}[2]{\left\lfloor\frac{#1}{#2}\right\rfloor}

\newcommand{R}{\mathcal R} \newcommand{L}{\mathcal L}

\newcommand{S}{\mathcal S}

$This answer is based on an answer to a related question,

but generalized to account for uniform squares of any size within a rectangle of any size. The sides of the rectangle do not even need to be commensurate with the sides of the squares.

It is assumed, however, that all squares placed in the rectangle are placed with their sides parallel to the sides of the rectangle.

(It seems intuitively obvious that rotating the squares will not enable more squares to fit in the rectangle, but proving it is another matter.)

Given a rectangle $\R$ of width $W$ and height $H,$ where $W$ and $H$ may be any real numbers, we first determine how many squares of side $N$ can fit in rectangle $\R$ without overlapping.

That is, the sides of squares may touch other squares or the edges of the rectangle, but the interior of any square cannot intersect another square or the boundary of the rectangle.

We can show that the maximum number of squares that can be arranged in rectangle $\R$ in this way is $\idiv WN \times \idiv HN.$

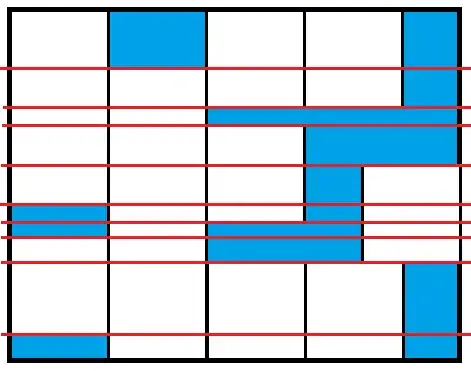

The following proof does this by constructing a rectangular lattice $\L$ of

$\idiv WN \times \idiv HN$ points such that in any such arrangement of squares inside $\R,$ each square must contain at least one point of $\L.$

Proof.

Choose a Cartesian coordinate system such that the vertices of rectangle $\R$ are at coordinates $(0,0),$ $(0,W),$ $(H,W),$ and $(0,H).$

Let

\begin{align}

w &= \frac{W}{\idiv WN + 1}, \\[0.7ex]

h &= \frac{H}{\idiv HN + 1},

\end{align}

and let $\L$ be the set of points $(jw, kh)$ where $j$ and $k$ are integers,

$1 \leq j \leq \idiv WN,$ and $1 \leq k \leq \idiv HN.$

In other words, we can tile rectangle $\R$ completely with rectangles of

width $w$ and height $h,$ and let the set $\L$ consist of all vertices of these rectangles that are in the interior of rectangle $\R.$

The points of $\L$ then form a rectangular lattice with

$\idiv WN$ points in each row and $\idiv HN$ points in each column,

a total of $\idiv WN \times \idiv HN$ points altogether.

Since $\idiv WN + 1 > \frac WN,$ it follows that $w < N,$ and similarly

$h < N.$

Therefore if we place a square $\S$ of side $N$ anywhere within rectangle $\R$ with sides parallel to the sides of $\R,$

at least one of the lines through the rows of points in $\L$ will pass through the interior of $\S,$ and at least one of the lines through the columns of points in $\L$ will pass through the interior of $\S;$ therefore $\S$ will contain the point of $\L$ at the intersection of those lines.

That is, the interior of $\S$ must contain at least one point of the set $\L.$

Suppose now we have placed some number of squares of side $N$ inside

rectangle $\R$ so that no two squares overlap

(their boundaries may touch but their interiors must be disjoint).

Then no two of these squares can both contain the same point of the set $\L.$

By the pigeonhole principle, we can place at most

$\lvert\L\rvert = \idiv WN \times \idiv HN$ squares in this way.

On the other hand, an array of squares with $\idiv HN$ rows

and $\idiv WN$ columns fits inside rectangle $\R$

(using the "greedy algorithm"),

so it is possible to achieve the upper bound of $\idiv WN \times \idiv HN$

squares. This completes the proof. $\square$

In the question, however, we are allowed to arrange squares of side $1$ inside the rectangle, then ignore them and arrange squares of side $2$ inside the rectangle, then ignore those squares and arrange squares of side $3,$ and so forth, as long as at least one square can fit inside the rectangle;

and then the answer is the total number of squares of all sizes that were arranged in this way.

The final answer therefore is

$$

\sum_{N=1}^\infty \left(\idiv WN \times \idiv HN\right).

$$

Note that this is actually a finite sum, since for $N > W$ or $N > H$

all terms will be zero.

The last non-zero term of the sum is the term for

$N = \min\{\lfloor W\rfloor, \lfloor H\rfloor\}.

\endgroup$