What I can give you is a derivation of the method.

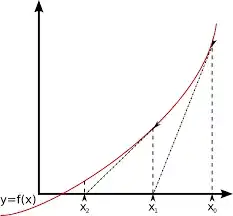

Assume some $x^*$ is some zero of $f$. Bcause $f$ is differentiable, sufficiently close at $x^*$ it looks like a straight line. So when you are not exactly in $x^*$ but close to it, then you can just take this line and look where this line intersects the $x$-axis instead of the more complicated function $f$. This is because the zeros of a linear function are very easy to determine. E.g. for $y=mx+n$ the zero is simply at

$$x =-\frac nm.$$

So say we are in $x_i$, close to $x^* $. At this point the curve looks like the line

$$y=f'(x_i)(x-x_i)+f(x_i).$$

This is the unique linear function through $f(x_i)$ with the appropriate slope to be a tangent to $f$. Now what is the unqiue zero $x$ of this line? Set $y$ to zero and rearragne and you will find

$$x=x_i-\frac{f(x_i)}{f'(x_i)}$$

in analogy to the zero for a general linear function $y=mx+n$. So when we call this new zero $x_{i+1}$, then starting from an estimation of a zero $x_i$, we found a better one.

This is essentially what the method does. It take an approximation and makes a better one. When your approximation is bad, so will the result be bad too (maybe).

Note:

Newtons method does not always work. There are examples where the sequence of $x_i$ either diverges or oscilltes, either because there is no zero or your initial estimation was bad.