Let $f(z) = z^2-a$ with $a \neq - \frac 14$.

If $a>0$, $f$ has a repulsive fixpoint at $\tau = (1+\sqrt{1+4a})/2$ (and most of the time, the other fixpoint is repulsive too, but let's take this one). I will note $\lambda$ the derivative of $f$ at $\tau$, which is $\lambda = 2\tau$ (larger than $1$), so near this fixpoint, $f$ acts almost like the dilation $g(z) = \lambda \tau$.

On a small disk $D$ around $\tau$ we can define $f^{-1}$ such that it sends $D$ to itself, and then according to Koenigs, there is a (unique) holomorphic injective function $h$ on $D$ into a small neighbourhood of $0$ such that $h(\tau) = 0, h'(\tau) = 1$, and forall $z \in D$, $h ( f^{-1} (z)) = g^{-1}(h(z))$.

Since $h$ is injective we can define $t = h^{-1}$ on $h(D)$, and then the functional equation can be put in the form $t(g(z))

= f(t(z))$ for $z$ close enough to $\tau$.

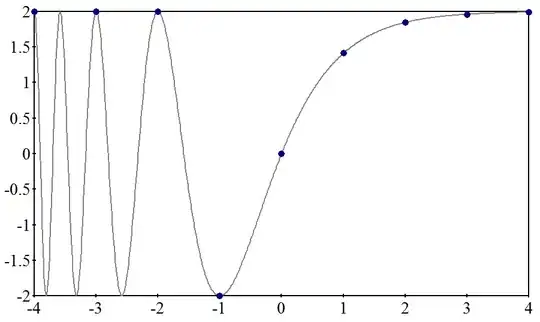

Now, since $g$ is a simple dilation and $f$ is entire, this means $t$ has an analytic continuation to the entire complex plane. $t$ has an essential singularity at infinity, so it takes every value infinitely often (with no exception because of the functional equation).

Let $w \in \Bbb C$ be a zero of $t$. It has a corresponding sequence $(y_n)_{n \in \Bbb Z}$ defined by $y_n = t(\lambda^{-n}w)$.

Then $y_0 = 0, y_1 = \pm \sqrt a, y_2 = \pm \sqrt {a \pm \sqrt a} \ldots$ and so on.

If you choose a value for $\log \lambda$, this allows you to interpolate the sequence to all of $\Bbb C$, defined by $y_n = t(w\exp(-n\log(\lambda)))$.

Suppose two zeroes $w_1,w_2$ give rise to the same sequence. Then, by the identity theorem we have $t(w_1z) = t(w_2z)$ forall $z \in \Bbb C$, and differentiating this relation at $z=0$ gives $w_1 = w_2$.

This work for any nonzero value too, so the points $(w,y_0)$ are in a bijective correspondance with the sequences $y_n = f(y_{n+1})$ that eventually converge to $\tau$.

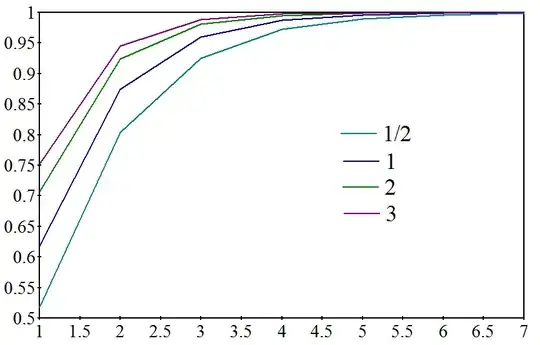

To compute the interpolation approximately, you can plunge into the sequence by applying $f^{-1}$, then once you are close enough to the fixpoint, approximate $f$ with $g$ to interpolate however you need, then go back by iterating $f$ :

$y_n = \lim_{m \to \infty} f^{\circ m}(\tau+\lambda^{-n}(y_m-\tau))$.

This works in theory, but you may run into precision issues for both iterations.

You may want to instead use a power series to approximate $t$ and $h$ once you're close enough to $\tau$.

If you wonder what the fractional iterates of $f^{-1}$ would look like geometrically, it seems they aren't necessarily algebraic : they should have branch points at all the critical values of $t$.

Differentiating the functional equation of $t$ gets you $g'(z).t'(g(z)) = f'(t(z)).t'(z)$, which means $\lambda t'(g(z)) = 2t(z).t'(z)$, so the critical points of $t$ are the the zeroes of $t$ (critical points of $f$) along with their images by any number of dilations.

Furthermore, $t'$ only has simple zeroes because iterating $f$ on $0$ will never loop back to $0$.

So the critical values are $0,f(0),f((0)),\ldots$, and there $t^{-1}$ (and thus all the fractional iterates, and well everything really) have a square root-like singularity.