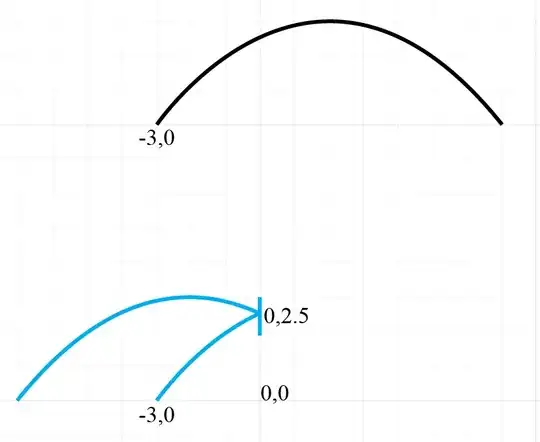

I would like to modify your original equations slightly by affixing subscripts to $v$ and $\theta$ to acknowledge the fact that they use the angle and speed of the projectile's motion at a particular point in space and time, namely, at the initial point $(x,y) = (x_0,y_0)$

and time $t = t_0$,

and also to take into account that $x_0$, $y_0$, and $t_0$ are not

necessarily all zero. (In particular, in your example in the question,

$x_0 = -3$.) The result is

\begin{align}

x &= x_0 + v_0 (t-t_0) \cos \theta_0, \\

y &= y_0 + v_0 (t-t_0) \sin \theta_0 - \tfrac12 g (t-t_0)^2.

\end{align}

There are other ways to express this, but this form of the equations

is relatively simple to write.

(The equation measures the "extra" amount of $x$, $y$,

and $t$ past the point $(x_0,y_0)$ and time $t_0$.)

We now consider another point in space and time further along the

initial trajectory, at the point $(x,y) = (x_1,y_1)$ and time $t = t_1$.

Note that you can uniquely determine $x_1$ and $y_1$ for any $t_1$,

you can uniquely determine $t_1$ and $y_1$ for any $x_1$,

and given a $y_1$ there are either two possible solutions, one possible

solution, or no possible solution for $t_1$ and $x_1$.

But however you decide to determine the values, we want to know all three

values $x_1$, $y_1$, and $t_1$.

We also want to know the speed $v_1$ and angle $\theta_1$

of the initial trajectory as it reaches $(x_1,y_1)$.

Taking the horizontal and vertical components

of the velocity at time $t$ as a function of $t$, we have

\begin{align}

v_x(t) &= v_0 \cos \theta_0, \\

v_y(t) &= v_0 \sin \theta_0 - g(t-t_0).

\end{align}

The speed at time $t$ is therefore

\begin{align}

v(t) &= \sqrt{(v_0 \cos \theta_0)^2 + (v_0 \sin \theta_0 - g(t-t_0))^2}.

\end{align}

The angle of motion at time $t$ is either

$$

\theta(t) = \arctan\frac{v_0 \sin \theta_0 - g(t-t_0)}{v_0 \cos \theta_0}

\quad\text{or}\quad

\theta(t) = \arctan\frac{v_0 \sin \theta_0 - g(t-t_0)}{v_0 \cos \theta_0} + \pi

$$

depending on whether $\cos\theta_0$ is positive or negative, respectively.

I'll assume from here on that $\cos\theta_0$ is positive.

So at time $t = t_1$, the speed and direction of the projectile are

\begin{align}

v_1 &= \sqrt{(v_0 \cos \theta_0)^2 + (v_0 \sin \theta_0 - g(t_1-t_0))^2}, \tag1\\

\theta_1 &= \arctan\frac{v_0 \sin \theta_0 - g(t_1-t_0)}{v_0 \cos \theta_0}. \tag2

\end{align}

Now suppose there is a flat surface through the point $(x_1,y_1)$ at angle

$\alpha$, where $\alpha$ is the angle between that surface and the

positive direction of the $x$ axis;

that is, $\alpha = 0$ for a horizontal surface, $\alpha=\frac\pi2$

($90$ degrees) for a vertical surface, and $\alpha=\frac\pi4$ ($45$ degrees) for a surface at $45$ degrees from horizontal, sloping upward to the right.

If we have perfect reflection of

a projectile moving in the direction $\theta_1$ as it strikes that surface,

the reflected path of the projectile will start at the angle

$2\alpha - \theta_1$.

So what we need to do is to reapply the equations for projectile

motion, but substitute $2\alpha - \theta_1$ as the new "initial angle",

and translate the "initial position and time" from the

point $(x_0,y_0)$ and time $t_0$ to the point $(x_1,y_1)$ and time $t_1$.

We do this by substituting $x_1$ for $x_0$, $y_1$ for $y_0$,

and $t_1$ for $t_0$ in the equation of motion.

The result is

\begin{align}

x &= x_1 + v_1 (t - t_1) \cos (2\alpha - \theta_1), \\

y &= y_1 + v_1 (t - t_1) \sin (2\alpha - \theta_1) - \tfrac12 g (t- t_1)^2,

\end{align}

where $v_1$ and $\theta_1$ are defined by Equations $(1)$ and $(2)$ above.

You can further manipulate these equations algebraically

to get them into the exact form you would like.

Alternative method

Another way to derive a formula is to use a little linear algebra.

We still need $x_1$, $y_1$, and $t_1$ at the point of impact on

the flat surface, but we avoid explicitly computing the speed

or angle of the incoming trajectory at that point.

We do still need to think about the velocity of the projectile

before and after the collision, but instead of speed and direction,

we use the $x$ and $y$ components of velocity, $v_x$ and $v_y$,

more directly.

It will help to represent the initial velocity in this form as well,

that is, set

\begin{align}

v_{0x} &= v_0 \cos \theta_0, \\

v_{0y} &= v_0 \sin \theta_0

\end{align}

so that $v_{0x}$ and $v_{0y}$ be the $x$ and $y$ components of velocity

at the start of the first part of the trajectory.

The equation of the trajectory can then be written

\begin{align}

x &= x_0 + v_{0x} (t-t_0), \\

y &= y_0 + v_{0y} (t-t_0) - \tfrac12 g (t-t_0)^2.

\end{align}

The components of a velocity vector at a later time $t$ in this part of the trajectory are then

$$

\begin{pmatrix} v_x(t) \\ v_y(t) \end{pmatrix} =

\begin{pmatrix} v_{0x} \\ v_{0y} - g(t-t_0) \end{pmatrix}.

$$

(I have put the components of the vector together in a $2\times1$ matrix

here because it is a convenient format for linear algebra.

Rest assured that we'll stop using this format when we get to the final

answer; I am using it just for the derivation of formulas.)

The next step will be to apply a transformation matrix to

reflect this vector around a line parallel to

the flat surface, passing through the origin. The reason we want the line to

pass through the origin is because vectors have no fixed "starting" position,

only a direction and magnitude; but if you imagine the "tail" of the vector

at the point $(0,0)$, then the transformation we want will leave the

"tail" of the vector in place and only move the "head".

We now have two choices on how to proceed, depending on how we represent

the inclination of the reflecting surface.

Using the angle of the surface.

If the reflecting surface makes an angle $\alpha$ with the $x$ axis,

then the reflection matrix is

$$

\begin{pmatrix} \cos(2\alpha) & \sin(2\alpha) \\

\sin(2\alpha) & -\cos(2\alpha) \end{pmatrix}

$$

(as shown in this answer to another question),

and the reflected vector is found by multiplying the incoming vector

by this matrix on the left. The resulting vector is

\begin{align}

\begin{pmatrix} v_{1x} \\ v_{1y} \end{pmatrix} &=

\begin{pmatrix} \cos(2\alpha) & \sin(2\alpha) \\

\sin(2\alpha) & -\cos(2\alpha) \end{pmatrix}

\begin{pmatrix} v_{0x} \\ v_{0y} - g(t_1-t_0) \end{pmatrix} \\

&= \begin{pmatrix}

v_{0x} \cos(2\alpha) + (v_{0y} - g(t_1-t_0)) \sin(2\alpha) \\

v_{0x} \sin(2\alpha) - (v_{0y} - g(t_1-t_0)) \cos(2\alpha)

\end{pmatrix}

\end{align}

Writing this as a system of equations without matrices,

\begin{align}

v_{1x} &= v_{0x} \cos(2\alpha) + (v_{0y} - g(t_1-t_0)) \sin(2\alpha), \tag3\\

v_{1y} &= v_{0x} \sin(2\alpha) - (v_{0y} - g(t_1-t_0)) \cos(2\alpha). \tag4

\end{align}

Using the slope of the surface.

If the slope of the reflecting surface is $m$, that is, the surface

is parallel to the line $y = mx$,

then the reflection matrix is

$$

\frac{1}{1 + m^2}\begin{pmatrix} 1-m^2 & 2m \\ 2m & m^2-1 \end{pmatrix}.

$$

(See this question and its answer.)

The reflected vector is therefore

$$

\begin{pmatrix} v_{1x} \\ v_{1y} \end{pmatrix} =

\frac{1}{1 + m^2}\begin{pmatrix} 1-m^2 & 2m \\ 2m & m^2-1 \end{pmatrix}

\begin{pmatrix} v_{0x} \\ v_{0y} - g(t_1-t_0) \end{pmatrix}.

$$

If you do the matrix multiplication, the result is equivalent to

the system of equations

\begin{align}

v_{1x} &= \frac{1}{1 + m^2}((1-m^2)v_{0x} + 2m(v_{0y} - g(t_1-t_0))), \tag5\\

v_{1y} &= \frac{1}{1 + m^2}(2m v_{0x} - (1-m^2)(v_{0y} - g(t_1-t_0))). \tag6

\end{align}

Of course this does not work for a vertical line of reflection,

but in that case we simply change the sign of $v_x$ at the point of impact.

Assembling the final result.

We already know how to write the equation of a trajectory that

starts with given $x$ and $y$ velocity components from a given point

at a given time; all we need to do is to take the values of $v_{1x}$

and $v_{1y}$ (either from Equations $(3)$ and $(4)$ or from

Equations $(5)$ and $(6)$) and plug them into these equations:

\begin{align}

x &= x_1 + v_{1x} (t-t_1), \\

y &= y_1 + v_{1y} (t-t_1) - \tfrac12 g (t-t_1)^2.

\end{align}

While this may seem like a long procedure, most of the writing above

is just explanation and proof; to actually use the procedure, after

determining $x_1$, $y_1$, and $t_1$ you merely take four of the equations above (selecting the ones that suit the way your surface is described)

and start evaluating them, using the known data.