Let's take Harry Truman as an example. He was born in 1884. The electron was discovered in 1897, which would have been Truman's freshman year at Independence High School. If he did take a physics or chemistry class at that school or at Spalding's Commercial College, models of the structure of atoms would not yet have been part of the standard curriculum. Maybe if he'd had a teacher who was exceptionally up to date on the latest advances in physics, that person might have mentioned the latest speculations on such things, including the brand-new plum pudding model of the atom. In that model, the atom consisted of some electrons along with a spherical part possessing a positive charge. Because chemical reactions don't change one element into another, the best understanding at the time was that the this spherical part was immutable. The spherical part didn't have a standardized name. Physicists might refer to it as the "nebula" or the "pudding," but for lack of a specialized term, generally they would just call it the "atom" and depend on context so that it would be clear they meant just the positively charged part.

If you wanted, for example, to change lead into gold, then you would have to split the lead "atom" (its positive sphere) into two smaller parts. This impossible feat would then be referred to as "splitting the atom."

The atomic nucleus was discovered around 1911-1913 by Rutherford et al. So Truman would have grown up knowing the word "nucleus" only as a word that could refer to things like the nucleus of a cell, or figurative usages such as "the nucleus of a new communist movement in Russia." Nuclear fission was discovered in 1938-9, so it was cutting-edge science during WW II. Laypeople like Truman didn't know about this kind of thing in any detail, and therefore didn't have the new and specialized vocabulary for talking about it.

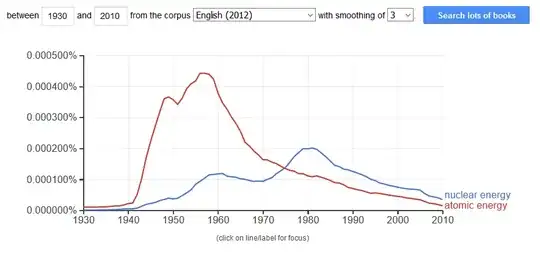

From a modern point of view, we would say that both fission and fusion are nuclear processes, and we would talk about "nuclear energy," "nuclear fission," and "harnessing the power of the nucleus." But when political and military leaders talked about these things in the WW II era, they would use the vocabulary that they already knew: "atomic energy," "splitting the atom," and "harnessing the power of the atom." As shown by Brian Z's google ngrams graphs, it took until ca. 1950-1970 for the more precise and appropriate technical terminology to filter into the popular consciousness. Even Jimmy Carter, who did nuclear engineering work in the US Navy, would pronounce the word as "nucular."

Mark C. Wallace wrote in a comment:

Atomic splits the atom (fission); nuclear fuses nuclei (fusion) - they are two different processes. Neither is more accurate in general.

This is wrong. Fission splits the nucleus. Fusion fuses nuclei. Both are nuclear processes. Examples of atomic processes are things like chemical reactions, fluorescence, or the emission of light by a neon sign.