Short Answer

For the most part, we have little evidence for the naming of shops, especially before the Late Middle Ages in Europe. Visual evidence suggests that almost all shops did not publicly display a name but some did display an object representing their trade. A surviving example of a shop name from England is La Corner Schoppe, while in Italy at least a merchant might use his family name. In China, medicine shop names were common in the 10th and 11th centuries at least, examples including Infant Malnutrition Medicine Shop and Ugly Granny Medicine Shop.

Details

Our evidence for medieval Europe is patchy. David Garrioch, in the article House names, shop signs and social organization in Western European cities, 1500-1900 (Urban History Vol. 21, No. 1 (April 1994), writes:

The history of shop signs reaches back at least to Roman times. In

northern Europe, however, the earliest traces seem to date from the

thirteenth century, although it is possible that they were in use

before then. By the sixteenth century both signs and names seem to

have been numerous all over Europe, and the evidence suggests that

their numbers continued to increase in most cities until the

eighteenth century.

In a footnote, Garrioch cites evidence from Adolphe Berty (1855). He

found two in Paris from 1206 and 1212. He argued that they were

probably more numerous than the records suggest, but he adds that

there was no doubt less need for them in the less crowded outer areas

than in the city centre

In a study of one part of Paris by Berty published 5 years later

the earliest sign found...dates from the 1340s and the house-lists for

this part of Paris in 1280 do not contain any.

For London, the oldest shop sign with a name found is from 1278, according to the BBC article La Corner Schoppe: the funny origins of shop names:

The earliest recorded shop name is La Corner Schoppe [sic]. The name was

found in a document written in 1278 in Westminster, London. However

there were numerous Corner Shops throughout the 1200s onwards, but

most would have taken the name of the building.

The orginal source for 'La Corner Schoppe' (actually 'la Cornereschoppe') is the Calendar of Wills Proved and Enrolled in the Court of Husting, London: Part 1, 1258-1358 (ANNO 7 EDWARD I)

Readings in Medieval History, Volume II has primary source material on a Florentine merchant, Stagio, who used his own name for his shop, but it's not clear if this was displayed or not.

The history of signboards: from the earliest times to the present day is a dated source (1867) quite detailed:

...signs were of but little use. A few objects, typical of the trade

carried on, would suffice; a knife for the cutler, a stocking for

the hosier, a hand for the glover, a pair of scissors for the tailor,

a bunch of grapes for the vintner, fully answered public

requirements. But as luxury increased, and the number of houses or

shops dealing in the same article multiplied, something more was

wanted. Particular trades continued to be confined to particular

streets ; the desideratum then was, to give to each shop a name or

token by which it might be mentioned in conversation, so that it

could be recommended, and customers sent to it. Reading was still a

scarce acquirement; consequently, to write up the owner's name would

have been of little use.

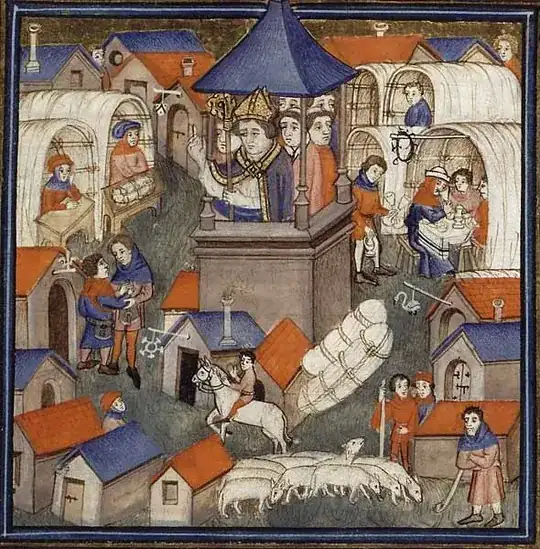

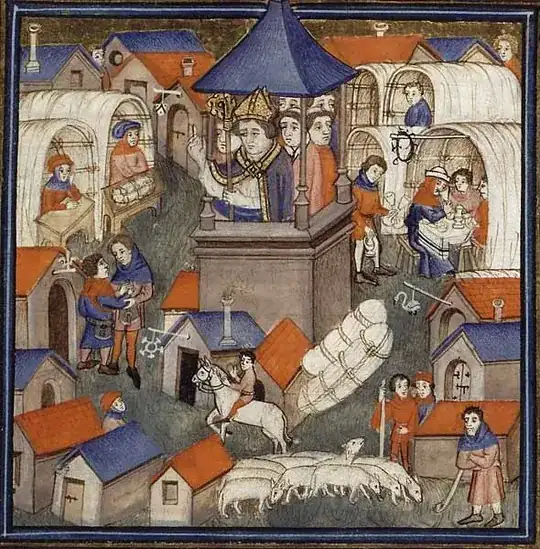

Looking at images of medieval art seems to confirm the above. Most shops have no sign of any kind, but a few have objects - see, for example, and the images below.

Siena, 1300s.

"Pontifical de Sens, France, XIVe siècle". Source: BnF, previously posted by LangLangC in his answer to another question.

The webpage Merchants’ Stalls & Shops has links to more images from various European cities. The only sign with writing is this "Hand-colored 19th-century woodcut reproduction of a medieval illustration", but even here none of the other establishments visible seem to have any signage (there's a better image here). There are also a number of illustrations of shops (salt, cheese, butcher's shops) in the Tacuinum Sanitatis but none appear to have names displayed.

Selling salt in a shop, miniature from Tacuinum sanitatis, end of 14th century. Source: habsburger.net

Without saying so explicitly, it seems that medicine shops in 10th & 11th century China had shop signs. A Social History of Medieval China gives numerous examples of shops with names (including the imaginatively named Ugly Granny Medicine Shop), but doesn't actually directly say they had names on signs.