I have heard that extreme storm events can be caused simply by a butterfly flapping its wings somewhere in a distant location. Is it true that such a small disturbance in the air in one location can result in such a large catastrophic event in another separate location? If so how can we know this is possible, and how is this even possible?

-

2This question is off-topic because it is not scientific. It can't be answered by scientific methods. No experiment can be constructed to test any of the answers' truth or falseness. Thought experiments aren't enough. Even the OP asks "How can we know this is possible?" It's a meta-physical question. – kwknowles Apr 21 '14 at 02:30

-

2@kwknowles, I disagree with you about the scientific nature of the question. Many questions in physics are answered through simulations and they are not considered unscientific if you have a simulated model for some phenomenon. Whether we have such simulations or not I don't know but it is beside the point, the question can theoretically be answered via a scientific approach. – Kenshin Apr 21 '14 at 02:34

-

@Mew It's not a matter of how you test a theory. In order to use the scientific method a theory must be testable. In order to test the theory, data must be collected. Simulations are used in the scientific method, but they can't be used in place of real world data in order to test a theory. This isn't just my opinion, see Scientific method. I'm only harping on this because we are defining the site right now. See Level of the questions so far – kwknowles Apr 21 '14 at 17:36

-

2@kwknowles, Suppose a medicine has been shown in clinical trials to benefit all humans it is tested on. I can approach a scientist and ask would the medicine benefit me. The scientist could say, that's untestable and unscientific - true. It is untestable because even if I take the medication and get better, there is no way to know I got better because of the medication. Does this mean all such questions fall out of the realm of science? NO. This is the nature of APPLIED SCIENCE. It is taking a model that we have developed through science, and applying that model to specific situations. – Kenshin Apr 21 '14 at 23:38

-

2@kwknowles, now in this case, theoretically it is possible that we could develop a predictive model of weather, that is testable. After testing it many times, we could then plug in the initial conditions with and without butterflies flapping their wings and so on, and check the results. Now it doesn't matter weather this particular scenario is testable or not, if the underlying model is testable, then it is applied science. This is analogous to the medical situation, where the underlying model is that the medicine works, and then we apply it to an individual patient. – Kenshin Apr 21 '14 at 23:41

-

1@Geodude Regarding your comment that the question was reopened. Why address it to me? I didn't close your question or even vote it down. I guess you assumed because I put that "off topic" comment. It's not a criticism of you (or the question, even). That's a comment meant for everyone who answers or reads the answers. I don't know where else to put a comment like that. – kwknowles Apr 22 '14 at 19:08

-

@kwknowles: While you're technically right, I think the question works well if taken as an iconic metaphor of small perturbations leading to large effects. That is testable: for example, you can set up repeatable physical fluid-dynamics experiments that have only extremely small initial differences, and show that eddies for in different places, at different times. – naught101 May 05 '14 at 04:52

5 Answers

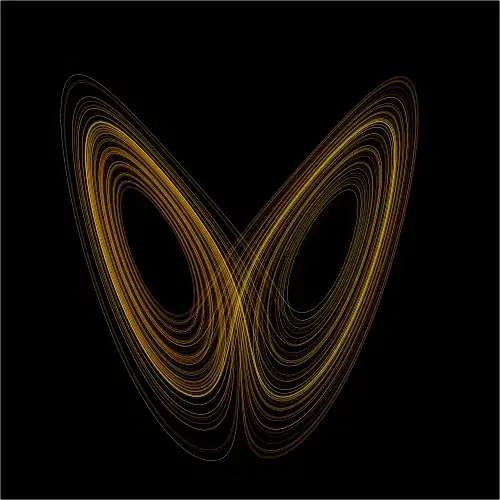

The butterfly is a colourful illustration of Chaos Theory, and the word butterfly came from the diagram of the state space (see below).

A system that is chaotic is extremely sensitive on its initial value. In principle, if you know exactly how the state of the universe is now, you could calculate how it develops (but due to other reasons, it is theoretically impossible to know the state exactly — but that's not the main point here). The issue with a chaotic system is that a very small change in the initial state can cause a completely different outcome in the system (given enough time).

So, suppose that we take the entire atmosphere and calculate the weather happening for the next 20 days; suppose for the moment that we actually do know every bit. Now, we repeat the calculation, but with one tiny tiny bit that is different; such as a butterfly flapping its wings. As the nature of a chaotic system is such that a very small change in the initial value can cause a very large change in the final state, the difference between these two initial systems may be that one gets a tornado, and the other doesn't.

Is this to say that the butterfly flapping its wings results in a tornado? No, not really. It's just a matter of saying, but not really accurate.

Many systems are chaotic:

- Try to drop a leave from a tree; it will never fall the same way twice.

- Hang a pendulum below another pendulum and track its motion:

(Figure from Wikipedia)

- Or try to help your boyfriend in what must be one of the loveliest illustrations of Chaos Theory ever. Suppose you are running to catch the bus. You keep sight of a butterfly, which delays you by a split second. This split second causes you to miss the bus, which later crashes into a ravine, killing everyone on board. Later in life, you go on to be a major political dictator starting World War III (Note: this is not the plot of the linked movie, but my own morbid reinterpretation).

Tell me, did this butterfly cause World War III?

Not really.

(Figure from Wikipedia)

- 11,704

- 2

- 37

- 87

-

It would be accurate to say that the butterfly was a contributing factor though :P – naught101 Apr 18 '14 at 09:35

-

1I think I finally figured out what bugs me about this answer. It's interesting, even fun to think about, but it's not scientific. Science consists of testable hypotheses. A theory isn't true just because it makes sense. You have to be able to design an experiment, collect data, and test the truth or falseness of the claims. If you released butterflies into a number of storms you might see more than usual tornados (I doubt it), but you could never say any particular tornado was caused by a butterfly. The way this answer is constructed, butterflies could cause anything. – kwknowles Apr 19 '14 at 23:35

-

3@kwknowles We cannot design a physical experiment to verify or falsify the hypothesis posed in the question, so we need to work by analogy and models. We do know that arbitrarily small changes in initial conditions can result in very large changes in a final situation. Wether or not this should be called a cause is a matter of definition. Ultimately, I think this question is more about semantics than about testable hypothesis. In the strict sense that you might prefer to see an answer, the question is unanswerable. – gerrit Apr 21 '14 at 13:02

-

1@gerrit Analogy and models are only one part of the scientific method. The hypothesis must be testable. The question might be OK here if the answer pointed out that it's not really a scientific question. However, this answer is definitely off topic. It's just wool gathering. See Level of the questions so far – kwknowles Apr 21 '14 at 17:17

-

@kwknowles, the question states at the end "how can we know if it is true?" The answer is we can't, but we can work out that it may likely be true if the models of our weather are consistent with it. The science is in the generation of models, but my question is more about applying such models to the butterfly case. – Kenshin Apr 22 '14 at 01:46

-

@GeoDude Look at it this way. The but-for-a-butterfly-flap "theory" can be used to explain anything. Can a butterfly push me off a cliff? Yes. If you're teetering right on the edge and that's all it takes is just one puff of air, then whoops, over you go. Can a butterfly cause an airplane to crash? Yes. If it's right there on the nick of disaster and all it takes is one more puff of air, then BOOM, butterfly destroys jet liner. See how useless it is as a scientific theory? It doesn't help us understand how the world really works. – kwknowles Apr 22 '14 at 18:53

-

@kwknowles It does help us, although I think your examples are not very good. It's not a matter of being just on the edge; it's a matter of a system going through an entirely different path when a small change happens. Can a butterfly cause a traffic accident? Easily, if I'm cycling and it distracts me. The point is that any change, no matter how small, can change the course of the universe... forever. – gerrit Apr 22 '14 at 18:58

-

@gerrit That's not a very useful definition of "cause". If you make it that broad, you're saying anything can cause anything. Like I said before... it's a beautiful meta-physical theory. It's just not Earth Science. – kwknowles Apr 22 '14 at 19:26

-

@kwknowles I agree that the word cause is not the best one to use here. The question used result in, but I'm open to other suggestions. It's just semantics, really. Regardless of the formulation, I think understanding the principles of chaos does further our understanding of how nature works. – gerrit Apr 22 '14 at 19:30

-

I love your bus example of Chaos Theory! I heard a similar explanation of it where a butterfly flies past a woman after just landing on a flower. The pollen causes the woman to sneeze, a man says "God Bless You" (or appropriate phrase). The man and woman end up talking more...marriage...kid... The kid turns out to be [insert dictator name such as Hitler, Stalin, etc.] all originated with a butterfly with pollen on its wings causing a woman to sneeze. Chaos Theory is an interesting topic. => – L84 May 05 '14 at 03:45

-

1This answer somewhat misrepresents the connection between chaos theory and weather. No one has claimed that weather is sensitive to arbitrarily small differences in initial atmospheric conditions. The "size" of the difference has an associated time-scale of applicability. Small perturbations have short time-scales and therefore localized effects. Large perturbations have longer time-scales and therefore greater range of impact. This answer needs to cite references if it wants to claim otherwise. Specifically where does the arbitrarily small idea (wrt weather) come from? – kwknowles May 05 '14 at 14:40

-

@kwknowles The arbitrarily small with regard to weather comes from the observation that even a numerical difference in a model initialisation (i.e. one bit difference) can result in an entirely different outcome in the long scale. It is my understanding that indeed arbitrarily small changes in the initial value can result in arbitrarily large changes in the long term, in any chaotic system, including weather. Is this a misrepresentation? – gerrit May 05 '14 at 14:49

-

@gerrit I tried to edit that out (misrepresentation) but I took too long to realize my mistake, i.e. that I don't actually know myself. So, is there a reference wrt to weather (and not weather models)? That sensitivity you talk about in the models is cited as a flaw. – kwknowles May 05 '14 at 14:53

-

@kwknowles It is my understanding that it follows directly from the observation that weather is a chaotic system (for which references are plentiful), and that any chaotic system shares this property. I haven't heard before that this is a property in weather models and is considered a flaw compared to the actual weather. The latter seems impossible to either verify or falsify. – gerrit May 05 '14 at 15:02

-

@gerrit The problem with the arbitrarily small differences in initial conditions leads to vastly different outcomes is that as the difference approaches zero you get a completely unpredictable system. Yet weather models are good for certain time scales--a day at least, right? To test this theory (and fix the models) scientists used Monte Carlo methods to randomly vary initial conditions. Instead of a uniform distribution of outcomes (every outcome is as likely as any other) they got a bell curve. The center of the curve is the prediction. This fits nicely with chaos theory strange attractors – kwknowles May 05 '14 at 18:58

-

@gerrit You give a lower bound of 1 bit. That's not arbitrarily small. Edward Lorenz states that the lower bound would be the accuracy with which we can measure observables. Again, not arbitrarily small. It's not nit picking. It's the difference between science and philosophy. It's the difference between anything can cause anything and a theory that furthers weather prediction. Would you consider changing "arbitrarily small" to "very small"? You could also quantify the changes in outcomes: an error in measuring X doubles every N days (or hours), for example. That would be science. – kwknowles May 05 '14 at 19:22

-

@kwknowles I have changed arbitrarily to very. I don't know enough about the topic to be quantitative (and I think it's not needed to answer this question). – gerrit May 06 '14 at 14:16

-

@gerrit The quantitative terms are absolutely necessary to the answer. In fact, they are the only thing of worth you could have added to the answer. Otherwise, you could have simply stopped after the link to the Wikipedia article "The butterfly is a colourful illustration of Chaos Theory" Since the rest of the answer just restates what's there. What's the accepted Lyapunov exponent for the phenomenon? Does a butterfly flap meet that threshold? If you're not an expert, perhaps you shouldn't have posted an answer. – kwknowles May 07 '14 at 17:05

-

@kwknowles I do not agree that the question as stated requires a quantitative answer. It did not ask if the result could occur 1 day/3 days/1 month later, it asked if it could occur at all. Expertise is relative; I believe my answer is useful, but I would certainly welcome a more thorough, mathematically expressed, quantitative answer. The same comment for the question itself: I do not think being quantitative is a necessary condition for a post (question or answer) to be scientifically sound. – gerrit May 07 '14 at 17:11

-

@gerrit I agree that quantitative answers are not required in the general case. I'm saying that quantitative information in this particular answer would have turned it from pop-sci/philosophy/repeat-of-already-available-info into an expert level question. – kwknowles May 07 '14 at 21:06

-

This is a pretty interesting discussion, but I'm worried that it will get lost in the future when a moderator comes along and decides to cull the lengthy discussion. Maybe a better way to deal with the disagreements would be to ask more questions? I know I have a couple of good references for an answer to the how behaviour in models relates (or doesn't) to the real world, for instance. – naught101 Sep 11 '14 at 14:20

Predictability: Does the flap of a butterfly's wings in Brazil set off a tornado in Texas?

That was the title of Edward Lorenz's invited talk at the 139th meeting of the American Association of the Advancement of Science held in 1972. This is the origin of the term "butterfly effect". The catchy title suggests that the answer must be "Yes!" Why else ask that question? The bulk of the talk says the answer is "Nobody knows." "Nobody knows" doesn't jibe well with a sensationalistic, unscientific press. That a butterfly in Brazil might trigger a tornado in Texas does.

Lorenz had discovered in 1961 that early 1960s weather simulations were incredibly sensitive to initial conditions. Did this mean the weather itself is incredibly sensitive to minute changes? That the answer to this question is also "yes" marked a very important discovery. Weather and climate are the quintessential chaotic systems. Lorenz's work marked the start of modern chaos theory. His seminal 1963 paper, Deterministic nonperiodic flow, has been cited 13479 times, per Google scholar. (In comparison, his 1972 talk has "only" been cited 345 times.) The vast majority of those 13479 citations came after his 1972 AAAS talk. Sometimes it takes a catchy title to catch the attention of a scientist.

Taking Lorenz's talk literally, asking whether a flap of a butterfly's wings in Brazil truly can set off a tornado in Texas, misses the point of his talk and of his work. The key point is that weather is chaotic. The accuracy of a detailed weather forecast fourteen days from now is rather low because that two week interval is well beyond the relevant Lyapunov timescale for such detailed predictions.

What about that butterfly? It's wing flap is a very small perturbation. It's rather difficult to say that that flap caused anything of significance to happen because the relevant timescale for such infinitesimally small perturbations is very short.

- 23,597

- 1

- 60

- 102

-

I've heard that the term "butterfly effect" had been suggested to him based on what his state space diagram looked like to a layman, but I have no authoritative source for this anecdote. – gerrit May 01 '14 at 13:36

-

This is a very good answer--succinct, informative, stays on topic. It really deserves to be number one and the accepted answer. – kwknowles May 08 '14 at 15:24

The causes of a single particular extreme weather event, like a tornado, may never be fully understood, especially if it is a chaotic system. The causes or contributing factors to the number of tornados expected for a particular atmospheric condition is much more fully understood and is certainly not chaotic. In that sense, butterflies do not cause tornados.

- 665

- 4

- 13

While it is not about butterflies, scientist have found weather in the United States and Noctilucent Clouds in Antarctica to be linked across thousands of miles.

Here are a few excerpts of what they have found:

New data from NASA's AIM spacecraft have revealed "teleconnections" in Earth's atmosphere that stretch all the way from the North Pole to the South Pole and back again, linking weather and climate more closely than simple geography would suggest.

For example, says Cora Randall, AIM science team member and Chair of the Dept. of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences at the University of Colorado, "we have found that the winter air temperature in Indianapolis, Indiana, is well correlated with the frequency of noctilucent clouds over Antarctica."

It demonstrates how apparently unrelated events can in fact be related to each other.

It's just a demonstration of cause-and-effect.

Over time(years and years) even the smallest motions compound, and the eddies from butterfies wings will be the difference between a tornado and a clear day.

- 1,524

- 2

- 14

- 22

-

3

-

1

-

3That didn't work out so well for Homer Simpson. Homer traveled back in time and stepped on an insect by accident which in turn created compounding impacts that completely changed society when he returned to the present time. – DrewP84 Apr 18 '14 at 03:25

-

1