Families of basis functions that are roughly sinusoidal are efficient for images I think because they can efficiently encode an edge at any spatial location. In images it is typical to have edges because foreground objects mask background objects of different color and because objects often have well-defined visible edges. It would probably be more efficient to encode edge locations more directly, but here we are talking about a weighted sum of basis functions.

One-dimensional experiment

Let's look at a simplified signal model that captures this "edginess" of images and find an optimal set of basis functions for that signal model in a block encoding setting. In the simplified model, images consist of flat surfaces separated by very rare edges. For simplicity, we only look at a single row in the image, making the signal one-dimensional (1-d):

Figure 1. Illustration of the image row signal model before discretization.

- To make experimentation easier, we won't deal with a signal as function of real numbers. Rather, we do a crude discretization: The signal is an infinitely long random sequence of numbers -1 and +1, starting with either value at equal probability.

- There is an infinitesimally small probability that a number is different than the previous number in the sequence. Such pairs of numbers represent edges in the image. Edges are assumed to be extremely rare.

- The signal is split into non-overlapping blocks of length $N$ and we intend to encode each patch separately. We'll call the blocks patches which is a bit more general word.

When $N = 8$, we have the following possible patches each described by a vector of length $N$. We also list for each patch the standard part (the nearest real number) of its hyperreal probability, and if that is zero, also the standard part of $1/\varepsilon$ times its hyperreal probability, where $\varepsilon$ is an infinitesimal number:

-1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 0.5

+1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 0 1

+1 +1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 0 1

+1 +1 +1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 0 1

+1 +1 +1 +1 -1 -1 -1 -1 0 1

+1 +1 +1 +1 +1 -1 -1 -1 0 1

+1 +1 +1 +1 +1 +1 -1 -1 0 1

+1 +1 +1 +1 +1 +1 +1 -1 0 1

+1 +1 +1 +1 +1 +1 +1 +1 0.5

-1 +1 +1 +1 +1 +1 +1 +1 0 1

-1 -1 +1 +1 +1 +1 +1 +1 0 1

-1 -1 -1 +1 +1 +1 +1 +1 0 1

-1 -1 -1 -1 +1 +1 +1 +1 0 1

-1 -1 -1 -1 -1 +1 +1 +1 0 1

-1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 +1 +1 0 1

-1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 +1 0 1

It's kind of a hierarchy of probabilities where we move on to the next level only if based on some condition we exclude all events with non-zero probability on the current level. It would also be possible to encounter multiple transitions within a patch, for example -1 -1 -1 +1 +1 +1 -1 -1, but the probability of seeing anything like that would be infinitesimally small even compared to $\varepsilon$. Such cases can be safely ignored because we won't be dividing anything by $\varepsilon^2$ and because we won't be having a condition by which we'd go to a third level in the hierarchy of probabilities.

A random patch equals -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 or +1 +1 +1 +1 +1 +1 +1 +1 at a probability infinitesimally close to 1, so the optimal basis vectors necessarily include a constant-valued sequence which perfectly encodes both. We will be using principal component analysis (PCA) by Octave's svd to find the optimal basis. Before that, we implicitly include the constant-valued basis vector by subtracting from each patch its mean.

In the resulting set of possible zero-mean patches, the zero-valued patch has a different probability than the rest. This imbalance would normally be a problem for PCA, but the encoding error will be zero for the zero-valued patch, eliminating the problem. We have eliminated the standard part of patch encoding error to zero, and will be minimizing the standard part of the sum of squares encoding error divided by $\varepsilon$.

All the work is done in Octave, with results following:

pkg load signal

pkg load statistics

N = 8;

function retval = step(n, k)

retval = [0:n-1] < k;

endfunction

x = [2step(N, [0:N-1]') - 1; 1 - 2step(N, [0:N-1]')];

y = x - mean(x, 2);

[coeff, score, latent] = pca(y); # https://octave.sourceforge.io/statistics/function/pca.html

plot(coeff.*sqrt(latent)', ".-");

Figure 2. Principal components of the zero-mean patches, weighted by the standard part of the square root of variance accounted for divided by $\varepsilon$.

Including the implicit constant-valued basis vector, the principal components look just like discrete cosine transform (DCT) basis vectors, and we can confirm this in Octave:

>> dct(coeff)

ans =

0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 -0.0000 -0.0000 0.0000 -0.0000

-1.0000 0.0000 0.0000 -0.0000 0.0000 -0.0000 0

0.0000 1.0000 0.0000 0.0000 -0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

0.0000 0.0000 -1.0000 -0.0000 0.0000 -0.0000 0.0000

0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 -1.0000 0.0000 -0.0000 0.0000

0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 1.0000 -0.0000 -0.0000

-0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 -0.0000 -1.0000 -0.0000

0 0.0000 -0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 -0.0000 1.0000

We really got the DCT basis vectors as the optimal basis for our signal model, at least for $N=8$. There are similar known relations between related matrix types and their eigenvectors. See this related Math Stack Exchange answer and Wikipedia, which says:

The normalized eigenvectors of a circulant matrix are the Fourier

modes

a.k.a. the discrete Fourier transform (DFT) basis vectors. Before subtracting the mean of each row, our test data is represented by a matrix of a related type, a Toeplitz matrix. I was wondering if there is a more general relationship between a row-mean-subtracted Toeplitz matrix and DCT. Based on some additional experiments I did (code at the end of the answer) with different signal models, DCT is the ideal basis for row-mean-subtracted Toeplitz matrixes arising from the signal being a cumulative sum of white noise, and not far from ideal when the signal is white noise filtered with almost any filter. Note that our edge signal is obtained by a cumulative sum of randomly located alternating positive and negative impulses. Natural images have a power spectral decay of approximately $1/\text{frequency}^2$ which is the power spectral decay of integration as a system. Integration is the continuous-time analog of a discrete-time cumulative sum. For the image statistics see Erik Reinhard, Peter Shirley, Tom Troscianko "Natural Image Statistics for Computer Graphics" University of Utah tech report UUCS-01-002, March 2001.

For the zero-mean patches, we can also do a comparison of how the predefined bases of Hadamard transform (WHT, W for Walsh), DCT and real-input real-output DFT (real-DFT) perform, in Octave:

function retval = cum_var(xformed, N = size(xformed)(1), sparse = false)

z = xformed.^2;

if sparse

z = flip(sort(z, 2), 2);

endif

z = sum(z);

s = sum(z);

retval = step(N, [0:N]')*z'/s;

endfunction

function retval = rfft(x, N = size(x)(1))

retval = zeros(size(x));

f = fft(x);

for c = 1:size(x)(2)

z = f(1:N/2+1,c);

retval(:,c) = [real(z(1)); sqrt(2)*reshape([real(z(2:end-1)) imag(z(2:end-1))].', [], 1); real(z(end))];

endfor

endfunction

function plot_cum_var(y, N = size(y)(2), sparse = false)

plot(0:N, cum_var(fwht(y')', N, sparse), ".-", 0:N, cum_var(dct(y')', N, sparse), ".-", 0:N, cum_var(rfft(y')', N, sparse), ".-")

if sparse

xlabel("Number of weighted basis functions included, descending variance order")

else

xlabel("Number of weighted basis functions included, ascending frequency order")

endif

ylabel("Standard part of fraction of variance accounted for / epsilon")

ylim([0, 1])

legend({"WHT", "DCT", "Real-DFT"},"location", "southeast")

endfunction

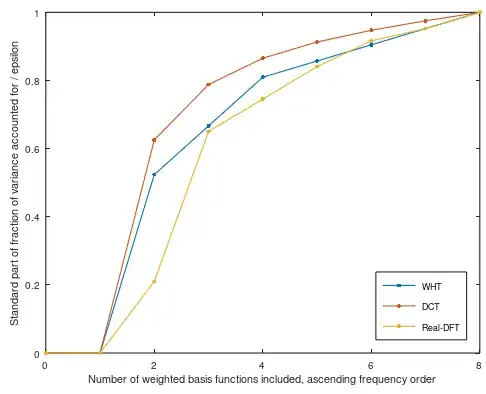

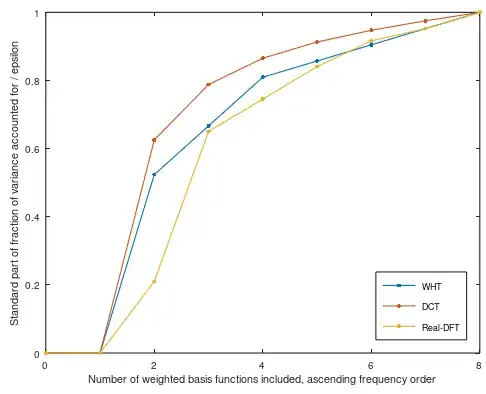

Truncated basis encoding plot_cum_var(y, N, false):

Sparse encoding plot_cum_var(y, N, true):

Figure 3. The standard part of the fraction of variance accounted for, divided by $\varepsilon$, by encoding the zero-mean patches using WHT, DCT or real-DFT basis.

It seems that DCT is a clear winner, as expected, and DFT and WHT lead each other depending on the choice between sparse and truncated basis encoding.

Our set of patch vectors with their associated probabilities can be seen as spatial discretization of the distribution of continuous-argument step-like patches with a continuously varying edge location, using uniform spatial sampling without anti-aliasing. The discretization accumulates to a single patch vector the probability of edge locations that fall between whole-number locations. A $1/\text{frequency}^2$ decaying envelope of the power spectrum of the continuous-argument signal model means that aliasing error due to sampling goes towards zero with increasing sampling frequency. Thus in some approximate sense our results also apply both to a band-limited, and a non-bandlimited continuous-argument rare-edge random signal model (Fig. 1) where the counterpart of the DCT basis would be the Fourier cosine series. It would be interesting to show/test this analytically somehow.

2-d patches

It would be interesting to see what the principal components would be for 2-d patches of flat images with rare edges in uniformly random directions and uniformly random locations across each 2-d patch.

Octave code for additional tests

#s = conv(rand(10000, 1), [1, 0.5])(2:end); # General filtered white noise

s = cumsum(rand(10000, 1))(2:end); # Cumulative sum of white noise

x = toeplitz(s(N:end), flip(s(1:N)));

y = x - mean(x, 2);

[coeff, score, latent] = pca(y);

imshow(abs(dct(coeff)))

#plot_cum_var(y, N, false)

#plot_cum_var(y, N, true)

#plot(coeff.*sqrt(latent)', ".-");