The OP clarified in comments that his real question/concern is with the transient response of the reflections that occur in a 1/4 wavelength transformer. In any typical application given the relatively high carrier frequency, meaning short wavelength, in comparison to the much longer symbol duration times, this transient would be of no consequence. Yet this is an interesting link between a common microwave component and signal processing, so I will explain further how this all ties together and can be modeled as a IIR filter to predict samples of the transient response in question. This will also help to quantify at what modulation bandwidth we would actually start to care about something like this.

Yes this is a signal processing answer, please read on!

First I will introduce some basics with 1/4 wave transformers sufficient to explain the signal processing. A quarter wave transformer is a relatively narrow band device that will match impedances (traditionally used in a microwave circuit). When the load impedance matches the source impedance we get maximum power transfer, and the 1/4 wave transformer will provide for such an equivalent match between a mismatched load and source. Specifically the 1/4 wave transformer is 1/4 wave at the center frequency of operation (and thus presents a 90° phase shift to the center frequency of operation, or $e^{-j\pi/2} = -j$ to propagate from one interface in the transformer to the other). In order to provide a perfect match between source and load impedance, the impedance of the quarter wave transformer must be the geometric mean. For example, to match a 200 ohm load to a 50 ohm source, the impedance for the transformer would be $Z_o = \sqrt{(50)(200)} = 100$ ohms.

Finally the reflection coefficient based on any mismatch is given by:

$$\Gamma = \frac{Z_L-Z_o}{Z_L+Z_o}$$

Which describes the magnitude (such as a voltage quantity) and phase of the waveform that would be reflected back at that interface. For example, as depicted in the diagram below, when the wave-front from the Source first meets the transformer, the reflection coefficient will be $(100-50)/(100+50)=+1/3$, so $1/3$ of the incident voltage will be reflected back toward the source (from this very first reflection in time, which is depicted by the arrows moving diagonally to the right; not depicted, but all subsequent reflections, eventually, will actually cancel this first reflection completely such that in the end the interface appears to be perfectly matched). Similarly some of the subsequent reflections are inverted 180°, such as when the wave-front that reflects back from the 100 ohm to 200 ohm interface (which also is +1/3) comes back and then is an interface going from 100 ohms to 50 ohms. In this case the reflection coefficient here is $(50-100)/(50+100)= -1/3$. $\beta$ is the transmission coefficient such that the total power between reflected and transmitted is equal to 1 ($\Gamma^2+\beta^2=1$)

Further, the wave will take time to transition the transformer from the Source Interface to the Load Interface, and this time delay is carefully determined to be a quarter wavelength or 90° at the center frequency of operation. Thus we see in the diagram above how first $\beta$ transitions the first interface from Source to Transformer, but becomes $-j\beta$ by the time it reaches the Load interface. The ratio of transformer to load impedance is the same to cause a reflection of +1/3, and thus we get $-j\beta\gamma$ as the complete internal reflection up to this point. More importantly with regards to overall transmission, we see how the first occurence of a transmitted waveform in time is $-j\beta^2$, and then after the time duration of back and forth in the transformer, we get an additional $-j\beta^2\gamma^2$ which will coherently add, and then again after another back and forth we will get an additional $-j\beta^2\gamma^4$, and so on as an infinite series.

OK, here comes some signal processing!

We have the case of an infinite series and specifically waveforms that add after integer increments in time which is a perfect opportunity to use the z-transform! Just as the z-transform eliminates all those exponentials in the Laplace Transform to give us simple polynomial forms, we can eliminate all the exponentials that could optionally be used to proceed with what I am about to show.

Similar to an FIR filter structure, the resulting output can be described as:

$$H(z) = -j\beta^2 -j\beta^2\Gamma^2z^{-1}-j\beta^2\Gamma^4z^{-2} + \ldots$$

Except of course as an FIR filter it would go on forever (which as we'll see is an IIR filter) Factoring out the common $-j\beta^2$ and expressing the rest as a summation we get:

$$H(z) = -j\beta^2(1 + \Gamma^2z^{-1}+ \Gamma^4z^{-2} + + \Gamma^6z^{-3} + \ldots$$

$$ = -j\beta^2 \sum_{n=0}^\infty \Gamma^{2n}z^{-n}$$

$$ = \frac{-j\beta^2}{1 - \Gamma^2z^{-1}}$$

We see that the summation converges to unity transmission (with a 90° phase shift), but also this is the transfer function for the equivalent IIR filter. From this, using practical numbers for the back and forth delay within the transformer given by $z^{-1}$ we can determine the equivalent analytic signal impulse response for the 1/4 wave transformer structure (meaning the lowpass equivalent impulse response relative to the center operating frequency).

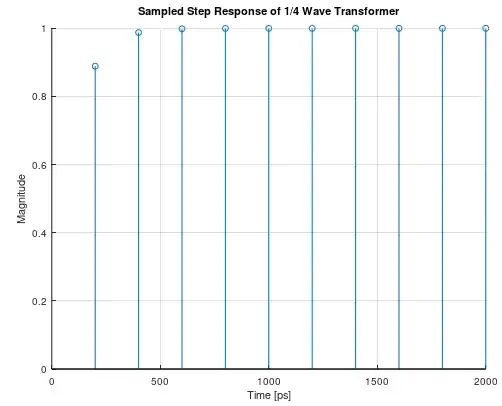

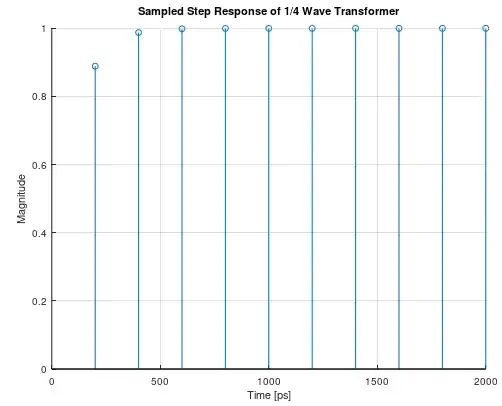

As detailed further below, a reasonable delay in implementation could be as long as 100 ps if implemented at 2 GHz as a microstrip trace on a circuit board. Doubling this for the round-trip delay associated with $z^{-1}$ would be 200 ps, or similar to a sampling rate of $1/200E-12= 100$ GHz (and we start to get a hint of why this won't effect an OFDM signal, at least the ones we use today). In the plot below is the resulting impulse response (or samples on the continuous time impulse response that would actually occur) for the example quarter wave transformer. As mentioned in the closing paragraph below, this is significantly faster than the coherence time of any OFDM waveform, such that the quarter wave transformer will certainly settle under condition of any dynamic transient conditions much faster than the transition time in the waveform. If the waveform was wideband enough for this to matter, this also would not be a functional matching structure since it is a relatively narrowband matching device (those bandwidth considerations are detailed further below in my original answer).

prior answer:

The 1/4 wavelength transformer is used in the RF path of the signal which in this case would be a relatively narrow bandwidth compared to the carrier, as far as considerations for 1/4 wavelength transformers go. This means (to bottom line it) there is little consideration on the spectral effects of the quarter wave transformer over the expected bandwidth of interest. I detail this further below.

The formulas for the quarter wave transformer that relate reflection coefficient and insertion loss to bandwidth relative to the perfect match at center frequency $f_o$ are given below and referenced here:

$$|\Gamma| = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1+\frac{4Z_o Z_L}{(Z_L-Z_o)^2}\cos(\pi f/(2 f_o))}}$$

Where:

$\Gamma$: Reflection coefficient (voltage reflected/voltage incident)

$Z_o$: Source impedance (or of first transmission line at input to transformer)

$Z_L$: Load impedance (or of second transmission line at output of transformer)

$f_o$: Center frequency where transformer provides perfect match ($\Gamma=0$)

$f/f_o$: Relative frequency related to center frequency

The insertion loss in dB is related to the reflection coefficient as follows:

$$S_{21} = 10\log_{10}(1-|\Gamma|^2)$$

I plotted these for two cases, a 2:1 mismatch and a 4:1 mismatch which provides us with an intuitive feel for how much we care about variation over frequency for practical examples such as OFDM carriers:

Consider a practical example with easy numbers of a 1/4 wavelength transformer matching a 50 ohm impedance to a 200 ohm impedance at 2 GHz. To properly implement this match, the transmission line would have an impedance equal to the geometric mean of the two impedances being matched or in this case 100 ohms. And with that for any signal components with a frequency exactly at 2 GHz, there would be no reflection and the incident wave would be fully delivered to the load (neglecting implementation losses). A wide OFDM channel is typically 20 MHz, but even if it was as wide as 100 MHz at this carrier, that would be a fractional bandwidth ($f/f_o$) of only 0.975 to 1.025. Even with this extreme mismatch (50 ohm to 200 ohm) we would see an insignificant loss and any distortion would be treated as flat fading (and very minor, and across the entire OFDM occupied bandwidth!), which would be of no concern whatsoever.

Further any temporal effects such as the impulse response of the transformer (which will occur as the initial reflections converge) will be unlikely to affect OFDM waveforms when comparing the inverse of the signal bandwidth to the propagation time for a typical quarter wave transformer at any given OFDM carrier where it would be practical to implement a transformer as a quarter-wave matching section. You could see this by determining the impulse response of the transformer (from each reflection converging) and then take the Fourier Transform to get the frequency response. The impulse response will manifest as an time constant with an effective bandwidth much wider than the modulated signal-- which means when the signal itself transitions, it can't transition fast enough to have the transient effect of the transformer to have any effect: by the time the signal has traversed a transition, the transformer will have long been settled. Consider in free space waves propagate at approx 3.3 ns/m (so ~ 2 ns/m on a circuit board) and what the distance would be for the particular carrier you have the 1/4 wave transformer at (which would only be practical to do above 2 GHz in most cases). So even as low as 2 GHz a 1/4 wave on a circuit board might be on the order of 0.5cm. This would take 106 ps to propagate from one end of the transformer to the other. Compare that to the coherence time of a 20 MHz OFDM waveform (~ 50 ns).