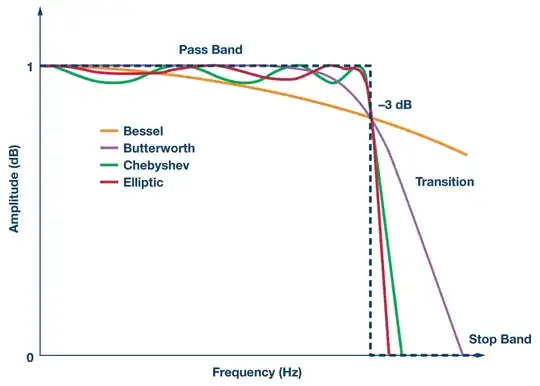

I have programmed a anti-aliasing filter that uses the fourier-transformation and makes a perfect cutoff on my desired cutoff frequency for downsampling without aliasing. I have read about other types of filters for anti-aliasing. Here i have a nice picture of different filters from this site:

The dotted line seems for me the perfect or ideal filter, but in practical it is not possible to filter a signal perfectly right? And therefore we can use different filters with different orders. Does this graph mean, the different filters do not filter completely on the perfect cutoff frequency and always contains a little aliasing?

The programmed FFT-Filter is used as followed in python:

def lowpass(x, binmax):

N = len(x)

return np.fft.irfft(np.fft.rfft(x, axis=0)[:binmax], N, axis=0)

x48hr is a Signal sampled with 48kHz and do a cutoff at 4kHz

lr_signal = lowpass(x48hr, binmax=len(x48hr)*4//48) #hr

I use this filter for generating low-resolution samples to train an convolutional neuronal network to learn the mapping between lr and hr to make a hr signal reconstruction.

In general I am actually trying to understand how much aliasing my measurements have and how I can use my measurements to study different types of filters and the aliasing in them. I want to increase the resolution of my signal, therefore I need aliasing in my low-resolution signals. I have asked another question regarding my problem here if you want to know more about it.