Summary:

- Don't just give any reason. a certain type of "grating" reason (as explained in 2nd half of my post) has been shown to backfire and be worse than none.

- A syntactically correct but semantically (fairly) meaningless reason could be classified as a peripheral route to persuasion. In low stakes situations, a vacuous (but not grating) reason may work better than none, but as the stakes increase so does the scrutiny applied to the reason.

Let me start by elaborating on experiments mentioned by Arnon Weinberg (because I think some of the details are necessary before trying to conclude from the perspective of later works):

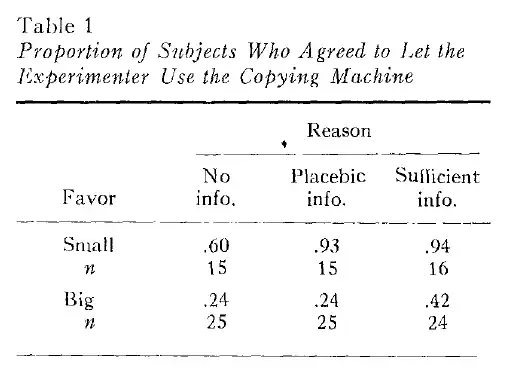

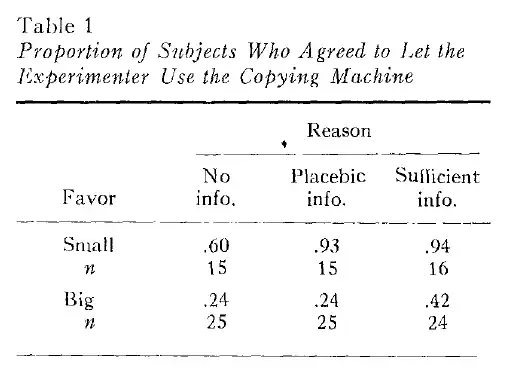

Actually Wikipedia doesn't detail the Xerox experiment well enough. The actual result was a bit more complicated: for small favors (in which the requester had fewer [actually 5] pages to copy than the recipient of the request [who had 20]) it made no difference whether the reason given was non-informative ("placebic") or real/plausible. But when the favor was "big" (the requester had more copies [20] to make than the recipient [who had 5]), the reason given did make a difference... and in fact giving a "placebic" reason was no better than no reason at all for big favors.

Also (contra to what Ana said) in the xerox experiment the reasons were terse, either bare request "Excuse me, I have 5 (20) pages.

May I use the xerox machine?" or +"because I have to make copies" ("placebic") or +"because I'm in a rush" ("real"). I think that Cialdini’s logic for always giving a reason is that in this experiment giving a reason was not worse than giving none (in any scenario), but also keep in mind that "not worse" does not equal "always better"; giving a "placebic" reason for a big favor didn't work (but also didn't hurt).

I think that in the Milligram subway experiment the reason given was worse than "placebic" though. In the xerox experiment you cannot really refute the "placebic" reason "because I have to make copies" with respect to the use of the xerox (you can't [easily] make copies otherwise). So while it may sound weird it's not that grating (to me). On the other hand in the Milligram subway experiment, the reason was "I can't read my book standing up" which is something that most people can mentally refute as probably fake right away... But this is just me theorizing. It would be nice if someone redid one of the experiments with 4 arms for the argument given: none, implausible, neutral/repetition, and plausible.

In the (very highly cited ~8K cites in GS, ~10x the Xerox experiment) "Elaboration Likelihood Model of Persuasion" of Petty and Cacioppo (1986), giving a "placebic" argument would probably be classified as a peripheral route to persuasion. They note (actually it's one of their "postulates") that

As motivation and/or ability to process arguments is decreased, peripheral cues become relatively more important determinants of persuasion.

By peripheral cues they mean among other things repetition (Trump being a good recent example, heh), distraction etc. I guess a "placebic" reason counts as a form of distraction. But also note that in the Xerox experiment the placebic reason is also a form repetition "I need X because I need X", alhouth with a slightly different formulation for the 2nd X.

Petty and Cacioppo actually discuss the Xerox experiment of Langer on p. 159, remarking after summarizing it that

Folkes (1985) provided a partial replication of this effect. In two field studies using the inconsequential request (making five copies), respondents were equally willing to comply whether the request containing the valid or the placebic reason. In a thind study, however, the subjects were asked to guess how they would respond to the requests and to "think carefully before answering". When instructed to think before responding, the valid reason produced significantly more anticipation of compliance than the placebic reason.

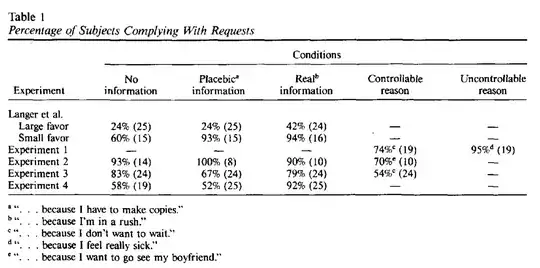

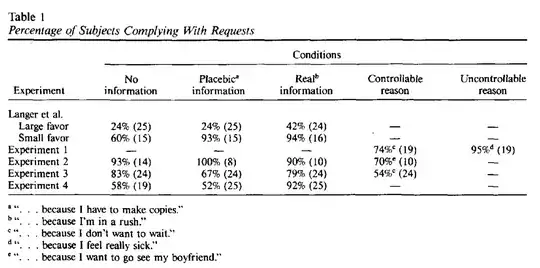

Furthermore!! Folkes pretty much did what I hoped someone would do, and also tested with an obnoxious reason:

Although providing a partial replication of Langer et al.(1978), Folkes takes issue with Langer's assertion that the placebic information is processed "mindlessly". Folkes argues that if the reasons are processed automatically under low consequences conditions, then a poor reason should as effective as a valid one. However she found a that a poor reason (e.g. "because I don't want to wait") was significantly less effective than a valid or placebic one under low consequence conditions.

So the conclusion is: don't just give any reason!

I'm not sure from which book of Cialdini the give-any-reason advice came. If it's from his 1984 Influence, then that could not have covered research that was published (a year) later. Cialdini has a 2001 book with the same title but a different subtitle though; hopefully that's more up-to-date, but I haven't checked.

Here's the actual data from Folke:

All requests were small in the Falke experiments (4 or 5 pages to copy) and also took place at two different locations; her experiment 2 was in the UK, the rest in the US. In Falke's experiments 1-3, she attempted to directly replicate (the small favor) experiment of Lange but with varying questions. Only in experiment 4 were the subjects instructed to think carefully before deciding.

The reason why Falke calls the grating reasons "controllable" is based on the level of volitional control (of the requester) implied in the reason:

Attribution research suggests that one distinction

between good and bad excuses is in

perceived controllability. An excuse can suggest

one is compelled to perform an action

or imply volitional control (Weiner, 1980).

Lack of control mitigates responsibility for a

transgression more than volitional control.

Thus, when people ask favors for reasons

they cannot control, their requests are more

frequently complied with than when reasons

for the requested favor are controllable

(Barnes, Ickes, & Kidd, 1979; Weiner, 1980).

In the copying machine paradigm, requests

to go first because of controllable reasons

(e.g., "because I don't want to wait") should

be complied with less—they do not mitigate

responsibility for needing the favor. When a

person lacks control over the reason for wanting

to go first (e.g., "because I feel really

sick"), compliance should be greater.

Finally, Petty and Cacioppo also distinguish some personality factors affecting the result, in particular what they call "need for cognition". Individuals that rated higher on a self-reported measure for this factor had (objectively) more polarized attitudes on an argument than individuals who scored low on this measure.